Classification of Birds

As Moss notes, any attempt to classify the world’s birds – or other living organisms – has always been subject to uncertainty.[1] This uncertainty is graphically illustrated by Edward Worth’s collections on ornithology, for Worth died in 1733 and therefore his collection predates the Linnaean system of classification. The classifications in his collection may not map onto our present systems but they are of major importance in showing us how sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writers about birds conceptualized their work. Worth possessed some of the earliest and most authoritative texts about birds: works by sixteenth-century authorities such as Pierre Belon (1517–64), Conrad Gessner (1516–65), and Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), and seventeenth-century authors such as Joannes Jonstonus (1603–75). When it came to classification, the jewel in his collection was undoubtedly his copy of Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), by Francis Willughby (1635–72), and edited by John Ray (1627–1705), which as Birkhead and Charmantier note, was the first book to actually use the term ‘ornithology’.[2]

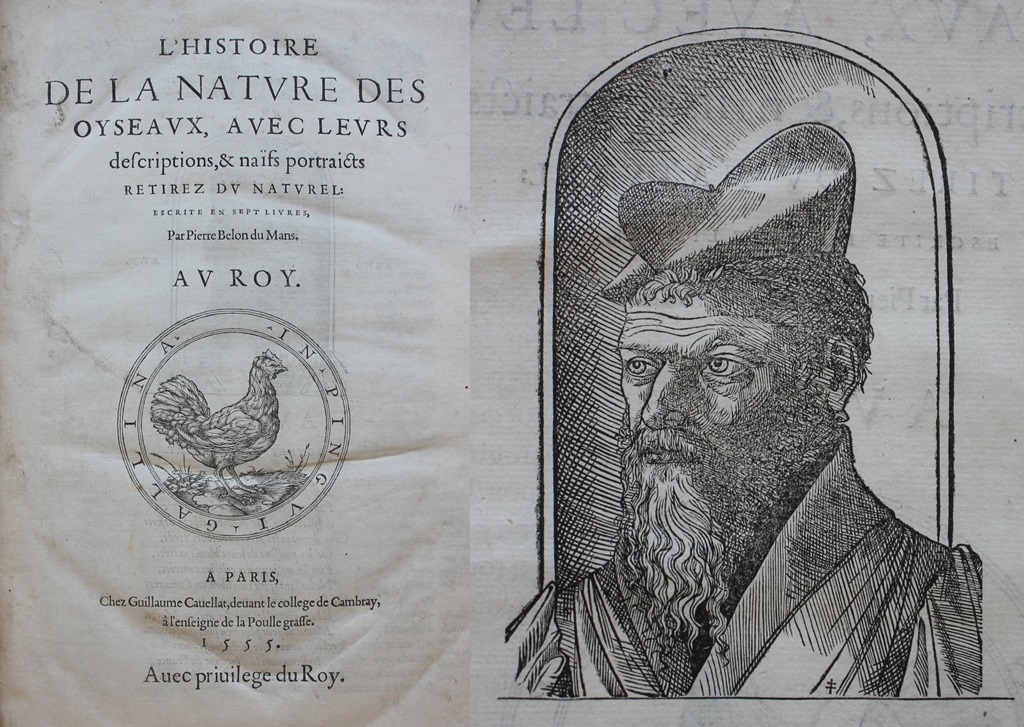

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), on left: title page; on right: Sig ā1v, portrait.

Worth also owned works by ancient authorities such as Aristotle (384–322 BC), and Pliny the Elder (23/24–79), and their influence, particularly that of Aristotle, may readily be seen in the sixteenth-century authorities working on birds. As Hall notes, Aristotle, when he suggested distinctions between birds, concentrated on ‘bodily parts and … their activities’, while Pliny the Elder’s Book X of Naturalis historia, in which he considered birds, was not organised in a systematic way.[3] Pliny pointed to birds’ feet as one way of distinguishing them, stating that ‘The primary distinction between birds is established especially by the feet; for they either have hooked talons or have digiti [presumably separate claws without hooks] or are in the web-footed class like geese and water birds generally’.[4] However, though he concentrated on feet rather than other body parts, he also divided birds by song and size.[5]

The sixteenth-century French natural historian Belon, though he noted what Aristotle and Pliny had said, offered a new approach. He had travelled widely throughout the Mediterranean and had already communicated his findings in his travel journal Les obseruations de plusieurs singularitez et choses memorables : trouuées en Grece, Asie, Judée, Egypte, Arabie … en trois livres (Paris, 1553), which Worth owned in a later edition of 1588. In his L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), Belon chose to concentrate on birds and provided his readers with a beautifully illustrated introduction to birds which, though he owed much to Aristotle, bore all the hallmarks of a work of original scholarship – he was describing and classifying birds he had, in the main, seen himself. Not all of the birds he described had been alive when he saw them – some, such as the exotic Brazilian Tanager was certainly dead and the bird he described was a skin. As Schulze-Hagen et al. note, this was by no means uncommon for most early modern commentators at some stage spoke about birds which were either mounted or mummified.[6] Belon himself included instructions on how to prepare bird specimens.[7]

There were substantial overlaps with Aristotle in Belon’s work – as Hall notes, his first group (birds of prey) was akin to Aristotle’s hook-taloned birds. So too were Belon’s second group (web-footed swimming birds) and his third group (fissipede waterside birds). His fourth group ‘dust-bathers’ were also very much like Aristotle’s ‘poor fliers’ but Belon was beginning to diverge from Aristotle by giving more information about habitat, and in his fifth group, in which he included a large group of crows, parrots, woodpeckers, pigeons and thrushes, he had broken with Aristotle almost completely.[8] The same was true of his sixth group in which he investigated the passerine (perching) birds, dividing them by what they ate: insects and seeds.[9] In all, his seven books consisted of 194 beautifully illustrated chapters, in which he emphasized the need for personal observation and the importance of habitat.[10]

Conrad Gessner, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), p. 594: Peacock.

Belon was not the only natural historian to publish a major work on birds in 1555 – his fellow scholar Conrad Gessner produced his third book of his encyclopaedic Historia animalium in the same year and it too focused on birds – Worth owned a later updated edition of 1617. Gessner’s Book III was enormous but it was but one volume of a multi-volume encyclopaedia in which Gessner’s aim was to provide ‘the total zoological knowledge of his time’, so while he certainly included descriptions of birds he had seen himself, he also provided the bibliographical architecture for the subject.[11] This was an enormous undertaking and no doubt because of the sheer scale of the endeavour, Gessner opted for an alphabetical approach, and thus did not attempt to classify birds into separate groupings. It was a remarkable undertaking. Gessner was the first to describe many birds of central Europe and many of his names were subsequently used by Carl Linnaeus (1707–78).[12] Gessner provided his readers with information about the plumage of a bird, its food, and song and (as was usual at the time), how it might be used by humans.[13] As Bruce notes, in all, Gessner provided his readers with illustrations of 217 birds, and, as Haffer argues, his massive undertaking ensured that Book III of Historia Animalium ‘remained the bird book in central Europe for over 100 years’.[14]

In a smaller work of the same year, Icones avium omnium quae in historia avium Conradi Gesneri describuntur (Zurich, 1555), Gessner did, however, provide a classification, placing birds into eight orders.[15] The first order began with birds of prey who flew by day and the second was devoted to birds of prey who hunted at night (i.e. owls). His third group continued a fascination with large birds ‘who fly strongly, which are not rapacious’.[16] Then he turned his attention to smaller birds, dividing them into those who ate fruit and worm eaters. His fifth group were the tame ‘dust bathers’ – terrestrial or low-flying birds and here he included pigeons. His sixth group were the wild dust bathers while his seventh group turned away from land fowl and focused on web-footed water birds. His eighth and final group were water birds who lived beside water – mainly waders with long legs.[17] There was much of Aristotle here and that is hardly surprising because Gessner was in effect attempting to be a new Aristotle by providing an overarching encyclopaedic work.

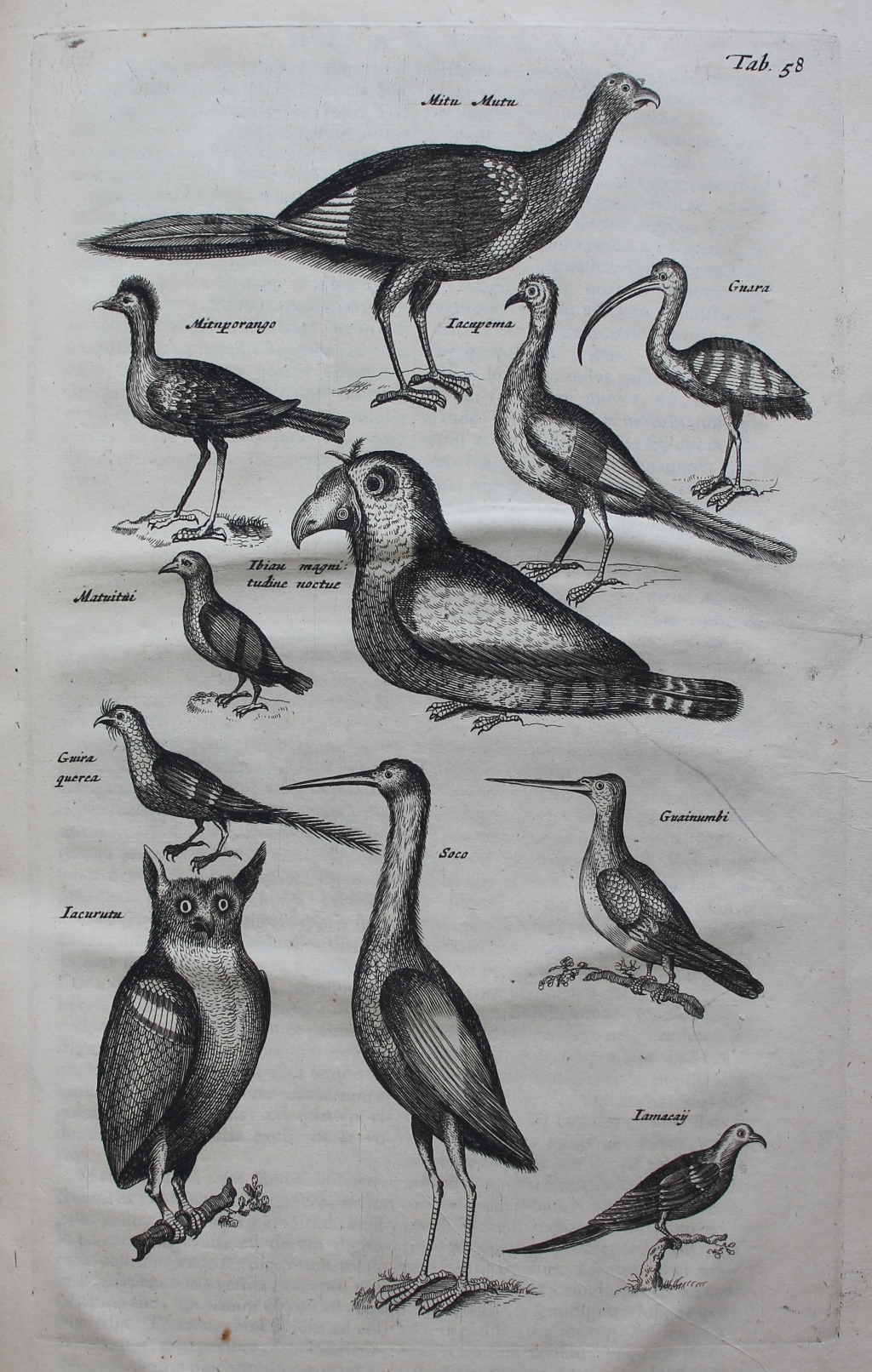

Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), Tab. 58.

Another sixteenth-century natural historian who chose the encyclopaedic route was Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), whose massive three-volume Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46), was also owned by Worth. Aldrovandi’s influence is readily apparent in the works of seventeenth-century commentators such as Joannes Jonstonus (1603–75). Aldrovandi’s volumes on birds were even more extensive than Gessner’s magnum opus and in it he sought to provide his readers with literally any information on any bird – whether it be real or mythical. Like Gessner’s, it was a collaborative effort, both in terms of text and image.[18] However, as Lind noted, at times, his ‘erudition submerged his critical judgment’, though it should be noted that Aldrovandi did, on occasion, add information based on his own experience, not least his explorations of bird anatomy.[19]

We have explored his classification scheme in our Aldrovandi exhibition, but suffice it to say that he too followed Aristotle in many things. He offered a basic division as follows:

The history of all the birds will be divided into three parts. In the first of them the birds just mentioned [i.e. the raptors] will be dealt with. The second will contain, beside the grain-eating birds (I mean the gallinaceous kinds, Pigeons, Peacocks, Pheasants, and others like them), those also which live on worms, and likewise which are omnivorous … In the third and last part all the birds will be described which either live habitually in water, like geese, diving birds, ducks, or which live beside water, like herons.[20]

The similarities with previous approaches are obvious. Like Aristotle, Belon and Gessner, he begins with ‘rapacious’ birds who fly by day, following up with nocturnal birds of prey. But unlike Belon, Aldrovandi was quite happy to include in his Book X mythical birds such as harpies, which are sandwiched uneasily between Book 9 (which deals with bats and ostriches), and Book XI (which is a lengthy book about parrots). As Hall notes, the positioning of Book IX mirrored that of Belon and Gessner.[21] The crow family (including woodpeckers), completed Aldrovandi’s first volume.

His second volume (Books 13–18), focused on ‘Dust bathers’ (including an in-depth investigation of hens and chickens), before he moved on to birds which both dust-bathed and washed (pigeons and sparrows). In Books 16 and 17 he turned to fruit and worm-eating birds, before finishing with song birds – though as Hall reminds us, most of Books 16–18 in fact dealt with small Passerine birds.[22] His third and final volume (Books 19–20), divided waterbirds into two groups: Book 19 concentrated on web-footed birds while Book 20 focused on birds living adjacent to water.[23] The influence of Aristotle’s Historia Animalium is clear.

The influence of both Gessner and especially Aldrovandi is readily apparent in Worth’s copy of Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), by the Polish scholar Joannes Jonstonus. This work was essentially an epitome of their huge tomes and it became very popular, being reprinted and translated a number of times. Jonstonus (also called Jan Jonston), had Scottish links – his father Szymon Johnston was of Scottish ancestry and his mother, Anna Becker, was German.[24] He was well-travelled: educated in Poland and Scotland, in 1629 he toured Europe, attended a number of universities (Franeker and Leiden in the Netherlands; Cambridge in England), and he would later visit Flanders, Brabant, France and Italy.[25] He was prolific, publishing a host of works on a dizzying range of topics but, as Matuszewski observes, his best book was his Historia naturalis – published between 1650 and 1653 in seven volumes, which contained one volume about birds.[26]

These were certainly weighty tomes but Jonstonus’s selection of information could, however, be quite idiosyncratic – his entries are entertaining but juggle concepts which often do not seem to fit together. In addition, as Mason points out, ‘the images of 569 birds that feature on the 62 plates of his Historiae naturalis de avidbus of 1650 are pillaged from Gessner, Aldrovandi and others down to the recent publication of the birds of Brazil by Georg Marcgraf’.[27] Thus Jonstonus’s dependence on earlier sources meant that in effect he added little to our understanding of classification – his focus was on habitat and food.[28] This criticism is perhaps a little harsh – as Matuszewski rightly argues, what Jonstonus was attempting to do was provide a textbook which would encourage more in-depth research – in his preface he made it clear that his target audience were ‘young students’.[29] And to be fair, he provided his readers with copper engravings of groups of birds (i.e. not plates of single birds), which are now divided into two distinct groups: land birds and waterbirds.[30] However, what was needed was a far more rigorous approach and luckily two men, Willughby and Ray, stepped forward to produce what is arguably the most famous book on early modern ornithology: Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), which Worth was lucky enough to own in a first edition of 1676.

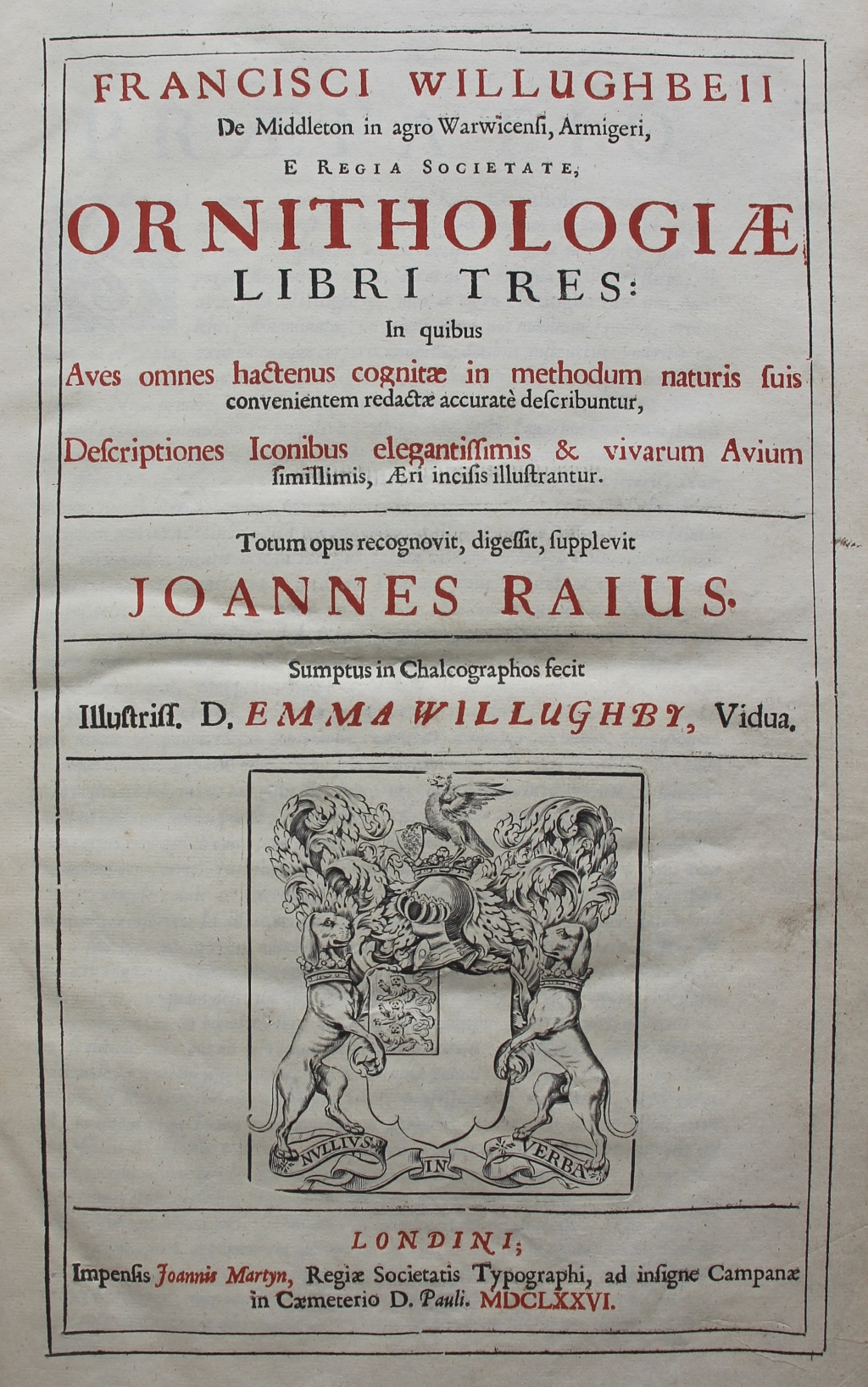

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), title page.

The publication of Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), was a major event for the Royal Society. Both authors were members of the society and the society had played an important role in the publication of the work. As the title page makes clear, this was a combined effort: the text was derived from the researches of two men, the virtuoso Francis Willughby, and his gifted scholarly companion, John Ray, while Willughby’s widow, Emma (1644–1725), provided the financial backing for the beautiful plates which accompanied this seminal text.

John Ray, who had been Willughby’s scholarly soul-mate in life and who was given the job of editing his papers after his untimely death, played a vital role in the 1676 Latin edition and added in yet more information to the 1678 English edition. This was clearly a labour of love for Ray, not only love of knowledge, but also a scholarly monument to someone who he clearly respected as a great scholar. Ray tells us of Willughby that:

He not only read what had been written by others, but did himself accurately describe all the Animals he could find or procure either in England or beyond the Seas, making a Voyage into forein Countries chiefly for that purpose, to search out, view and describe the several Species of Nature. And though he was not long abroad, yet travelled he over a great part of France, Spain, Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries. In all which places he was so inquisitive and successful, that not many sorts of Animals described by others escaped his diligence. For my part I know no man who hath seen more Species, been more exact in noting their differences, and inventing Characteristic Marks whereby they may be certainly distinguished; or more curious in dissecting them, and observing the make and constitution of their parts as well internal as external.[31]

Raven suggests that Ray was the prime mover and certainly Ray added not only to the English 1678 edition but also the Latin edition of 1676 for he tells us that he incorporated some descriptions from writers such as Gessner, Aldrovandi, Belon, Marcgraf (1610–c. 1643/4), Carolus Clusius (1526–1609), Francisco Hernández (1517–87), Jacob de Bondt (1592–1631), Ole Worm (1588–1654), and Willem Piso (1611–78), which had not been included by Willughby.[32] However, Ray himself puts the spotlight on Willughby who he paints as being almost obsessive in his pursuit of ornithological knowledge: ‘I must confess that in describing the colours of each single feather he sometimes seems to me to be too scrupulous and particular, partly because Nature doth not in all Individuals, (perhaps not in any two) observe exactly the same spots or strokes, partly because it is very difficult so to word descriptions of this sort as to render them intelligible: Yet dared I not to omit or alter any thing’.[33]

Willughby had left a good deal of material, material which Ray not only put in order and but also, as we have seen, augmented. In addition to his notes, Willughby had also amassed a collection of avian images:

Mr. Willughby made a Collection of as many Pictures drawn in colours by the life as he could procure. First, He purchased of one Leonard Baltner, a Fisherman of Strasburgh, a Volume containing the Pictures of all the Water-fowl frequenting the Rhene near that City, as also all the Fish and Water-Insects found there, drawn with great curiosity and exactness by an excellent hand. The which Fowl, Fishes, and Insects the said Baltner had himself taken, described, and at his own proper costs and charges caused to be drawn … Secondly, At Nurenberg in Germany he bought a large Volume of Pictures of Birds drawn in colours. Thirdly, He caused divers Species, as well seen in England as beyond the Seas, to be drawn by good Artists. Besides what he left, the deservedly famous Sir Thomas Brown, Professor of Physick in the City of Norwich, frankly communicated the Draughts of several rare Birds, with some brief notes and descriptions of them. Out of these, and the Printed Figures of Aldrovandus, and Pet. Olina, an Italian Author, we culled out those we thought most natural, and resembling the life, for the Gravers to imitate, adding also all but one or two of Marggravius’s, and some out of Clusius his Exotics, Piso his Natural History of the West Indies, and Bontius his of the East.[34]

It was thus a collaborative work in more ways than one for they were sent not only images but also descriptions of sighting by their correspondents. Coupled with this, as the above title page makes clear, Emma Willughby née Barnard, had provided the funds for the plates – something which Ray acknowledged both in the title page and preface of the 1676 first edition but which he omitted in the 1678 English edition. By then he was not living in the Willughby family home, nor teaching Willughby’s children for Emma had remarried in 1676 to Sir Josiah Child (bap. 1631, d. 1699).[35]

Ray explained their aim and method in the preface of the work – which made clear his distaste for epitomes such as that of Jonstonus:

As for the scope and design of this undertaking, it was neither the Authors, nor is it my intention to write Pandects of Birds, which should comprise whatever had been before written of them by others, whether true, false or dubious, that having already been abundantly performed by Gesner and Aldrovandus, nor to contract and Epitomize their large and bulky Volumes; lest we should tempt Students to gratifie their sloth so far as to take up with such Epitomes, and neglect the reading of the Authors themselves at large, which would be much more satisfactory and improving: and besides, this were but actum agere, such Epitomes being already made by Johnston: But our main design was to illustrate the History of Birds, which is (as we said before of Animals in general) in many particulars confused and obscrue, by so accutately describing each kind, and observing their Characteristic and distinctive notes, that the Reader might be sure of our meaning, and upon comparing and Bird with our description not fail of discerning whether it be the described or no.[36]

In short, they had a different aim from the earlier encyclopaedists: for Willughby and Ray personal observation was far more important than scholarly citation (though they included the latter also). What mattered was an eye-witness account of an actual bird, not a fable of something never seen.[37] They eschewed Aldrovandi’s composite approach which included ‘Hieroglyphics, Emblems, Morals, Fables, Presages, or ought else appertaining to Divinity, Ethics, Grammar, or any sort of Humane Learning’ and instead sought to present birds to their readers ‘only with what properly relates to their Natural History’.[38] Their focus was on the morphology of the bird, not (as in the case of Gessner and Aldrovandi), its etymology.

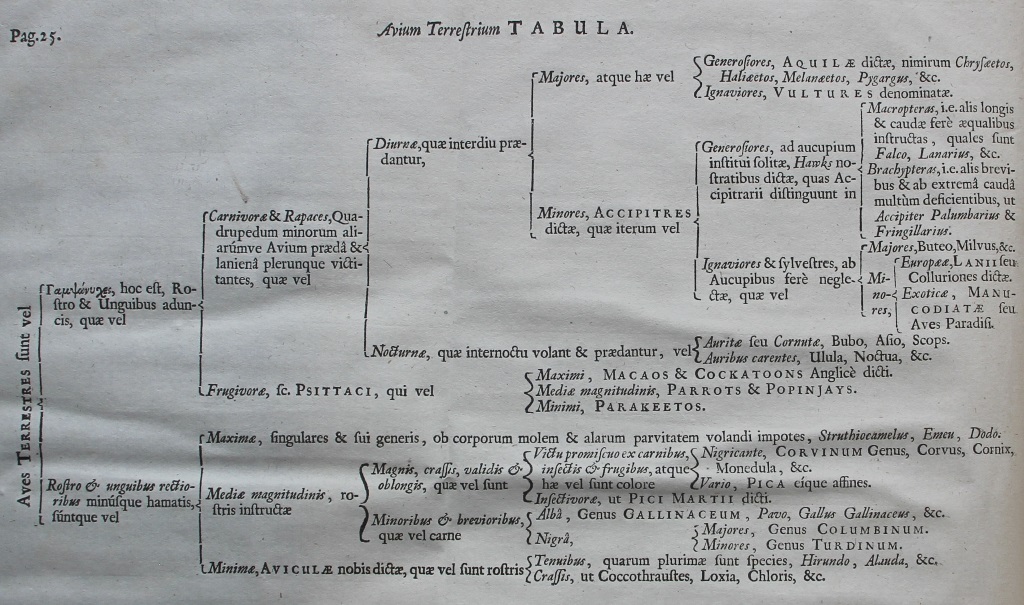

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), foldout plate at p. 25.

With admirable clarity Ray explained the structure of the work in the preface:

The whole Work we have divided into three Books. In the first we treat of Birds in general; in the second of Land-fowl; in the third of Water-Fowl. The second Book we have divided into two parts: The first whereof contains Birds of crooked Beak and Talons; The second, such whose Bills and Claws are more streight. The third Book is tripartite: The first part takes in all Birds that wade in the waters, or frequent watery places, but swim not; The second, such as are of a middle nature between swimmers and waders, or rather that partake of both kinds, some whereof are cloven-footed, and yet swim; others whole-footed, but yet very long-leg’d like the waders: The third is of whole-footed, or fin-toed Birds, that swim in the water.[39]

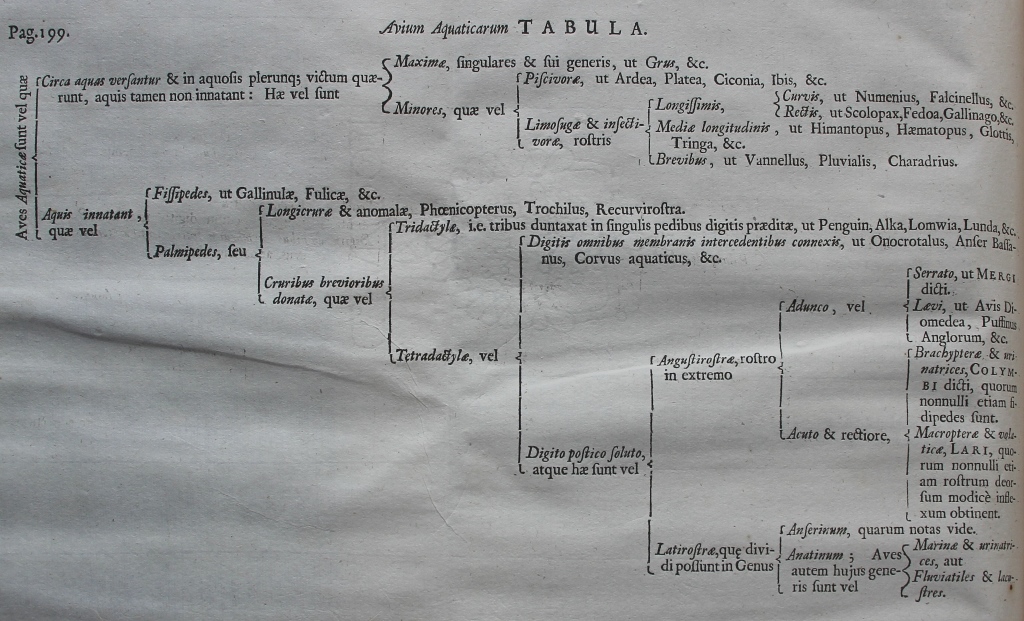

Chapter VIII guided the reader on the division of birds and in addition, they provided two tables which were intended to act as easy reference guides for readers, which explained in a succinct way the relationship between species. As Ray noted:

Nor will it be difficult to find out any unknown Bird that shall be offered: For comparing it with the Tables first, the Characteristic notes of the genus’s from the highest or first downward will easily guide him to the lowest genus; among the Species whereof, being not many, by comparing it also with the several descriptions the Bird may soon be found.[40]

The tables were divided between land fowl and waterfowl, which, as Hall notes, was not a system used by Belon, Gessner or Aldrovandi.[41] Their concentration on not only the claws of birds, but also their beaks, as a method of distinguishing them was innovatory.[42] Instead of folktales they measured any bird which came within their reach, recorded information about their bill and the colour of their plumage. They were far less interested in birds’ habitat and diet – instead a close study of their physical characteristics reigned supreme. As Haffer notes, they ‘based their classification of birds almost exclusively on form (structure) rather than function, mainly on the shape of the beak, the structure of the foot and body size’.[43]

‘Land fowl’ were divided between those with a crooked beak and claw and those with straight beaks. In the former group were carnivorous birds which were further subdivided into diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey (eagles, hawks and falcons in the first group, owls in the second). Birds with straight beaks might range from the large flightless birds such as ostriches; middle-sized birds with straight beaks (‘The Crow Kind’, ‘The Woodpecker Kind’, ‘The Poultry Kind’); and smaller birds with straight beaks (‘The Pigeon Kind’ and ‘The Thrust Kind)’.[44] Included in ‘Land Fowl’ were also ‘Small Birds with Slender Beaks’, as well as ‘Small Birds with Thick and Short Bills’ – thus including the Passerines (or Perching Birds).[45]

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), foldout plate at p. 199.

Water birds were divided into ‘such as frequent waters and watery places’ (waders) and ‘such as swim in the water’ (waterfowl). They were further divided by size (in the case of the first group), and feet in the case of the second (fissipede versus palmipede birds – i.e. birds with ‘cloven’ or separate toes, versus those which were web-footed). Hall rightly draws attention to the dichotomous nature of the divisions in the tables but reminds us that Willughby and Ray might not always stick to this rather rigid structure.[46] Despite some infelicities in the text – which Ray attempted to resolve in the 1678 edition – the Ornithologia libri tres was a tour-de-force, including eye-witness descriptions of around 230 species.[47] Raven rightly says that ‘The book itself will always remain an object of reverence to the ornithologist and of admiration to the historian’.[48]

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Aldrovandi on Chickens, translated and edited by L. R. Lind (Norman, Okla., 1963).

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Birkhead, T. R., and S. van Balen, ‘Bird-keeping and the development of ornithological science’, Archives of Natural History, 35, no 2 (2008), 281–305.

Birkhead, T. R., and I Charmantier, ‘History of Ornithology’, Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (2009), pp 1–8.

Boulger, G. S., ‘Willughby, Francis (1635–1672), naturalist’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Bruce, Murray, ‘A Brief History of Classifying Birds’, in Hoyo, Josep del, Andrew Elliott and David A. Christie (eds), Handbook of the birds of the world (Barcelona, 2003), vol. 8, pp 11–43.

Enenkel, Karl A. E., and Paul J. Smith, ‘Introduction’, in Enenkel, Karl A. E., and Paul J. Smith (eds), Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts (Leiden, 2007), pp 1–12.

Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617).

Haffer, Jürgen, ‘The development of ornithology in central Europe’, Journal of Ornithology, 148, Supplement 1 (2007), 125–53.

Hall, J. J., ‘The classification of birds, in Aristotle and Early Modern Naturalists (II)’, History of Science, XXIX, no. 3 (1991), 223–43.

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

Mandelbrote, Scott, ‘Ray [formerly Wray], John (1627–1705), naturalist and theologian’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Mason, Peter, Ulisse Aldrovandi: Naturalist and Collector (London, 2023).

Matuszewski, Adam, ‘Jan Jonston: Outstanding Scholar of 17th Century’, Studia Comeniana et Historica, 19 (1989), 1–10.

Mengel, Robert M., A Catalog of an Exhibition of Landmarks in the Development of Ornithology: From the Ralph N. Ellis Collection of Ornithology in the University of Kansas Libraries (Lawrence, Kan., 1957).

Moss, Stephen, Ten birds that changed the world (London, 2023).

Raven, Charles E., John Ray, Naturalist: His Life and Works (Cambridge, 1986).

Schulze-Hagen, Karl, et al., ‘Avian taxidermy in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance’, Journal of Ornithology, 144, no. 4 (2003), 459–78.

Smith, Paul J., ‘From philology to ornithology’, Humanistica Lovaniensia, 72 (2023), 123–38.

Welch, Mary A., ‘Francis Willoughby, F. R. S. (1635–1672)’, Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History, 6, no. 2 (1972), 71–85.

Wellisch, Hans, ‘Conrad Gessner: a bio-bibliography’, Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History, 7, no. 2 (1975), 151–247.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Moss, Stephen, Ten birds that changed the world (London, 2023), p. 169.

[2] Birkhead, T. R., and I. Charmantier, ‘History of Ornithology’, Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (2009), p. 2.

[3] Hall, J. J., ‘The classification of birds, in Aristotle and Early Modern Naturalists (II)’, History of Science, XXIX, no. 3 (1991), 225.

[4] Ibid., 223.

[5] Ibid., 225.

[6] On this see Schulze-Hagen, Karl, et al., ‘Avian taxidermy in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance’, Journal of Ornithology, 144, no. 4 (2003), 459–78.

[7] Ibid., 461.

[8] Hall, ‘The classification of birds, in Aristotle and Early Modern Naturalists (II)’, 228.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 229.

[11] Haffer, Jürgen, ‘The development of ornithology in central Europe’, Journal of Ornithology, 148, Supplement 1 (2007), 127.

[12] Ibid., 128.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Bruce, Murray, ‘A Brief History of Classifying Birds’, in Hoyo, Josep del, Andrew Elliott and David A. Christie (eds), Handbook of the birds of the world (Barcelona, 2003), vol. 8, p. 14; Haffer, ‘The development of ornithology in central Europe’, 125; 128.

[15] Worth did not own his work.

[16] Hall, ‘The classification of birds, in Aristotle and Early Modern Naturalists (II)’, 229.

[17] Ibid., 230.

[18] Mason, Peter, Ulisse Aldrovandi: Naturalist and Collector (London, 2023), pp 181–2.

[19] Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Aldrovandi on Chickens, translated and edited by L. R. Lind (Norman, Okla., 1963), pp xxxiv–xxxv.

[20] Quoted in Hall, ‘The classification of birds, in Aristotle and Early Modern Naturalists (II)’, 231.

[21] Ibid., 232.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Matuszewski, Adam, ‘Jan Jonston: Outstanding Scholar of 17th Century’, Studia Comeniana et Historica, 19 (1989), 1.

[25] Ibid., 2, 4.

[26] Ibid., 5.

[27] Mason, Ulisse Aldrovandi: Naturalist and Collector, p. 193.

[28] Matuszewski, ‘Jan Jonston: Outstanding Scholar of 17th Century’, 5.

[29] Ibid., 7; Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657), Sig. A3v. This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

[30] Mason, Ulisse Aldrovandi: Naturalist and Collector, p. 193.

[31] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), Sig. A2v–A3r. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[32] Ibid., Sig. A4r. On Ray’s role see Raven, Charles E., John Ray, Naturalist: His Life and Works (Cambridge, 1986).

[33] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, Sig A3r.

[34] Ibid. Sig. A4v.

[35] Welch, Mary A., ‘Francis Willoughby, F. R. S. (1635–1672)’, Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History, 6, no. 2 (1972), 77.

[36] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, Sig. A3v.

[37] Ray also mentions the importance of keeping birds – on the role played by bird-keeping in the development of ornithology see Birkhead, T. R., and S. van Balen, ‘Bird-keeping and the development of ornithological science’, Archives of Natural History, 35, no 2 (2008), 281–305.

[38] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, Sig. A4r.

[39] Ibid., Sig. (a)1r.

[40] Ibid., Sig. A3v.

[41] Hall, ‘The classification of birds, in Aristotle and Early Modern Naturalists (II)’, 234.

[42] Ibid., 235.

[43] Haffer, ‘The development of ornithology in central Europe’, 131.

[44] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, pp 21–4.

[45] Ibid., pp 24–5.

[46] Hall, ‘The classification of birds, in Aristotle and Early Modern Naturalists (II)’, 235.

[47] Raven, John Ray, Naturalist: His Life and Works, p. 326.

[48] Ibid.