Bird Anatomy

‘Most Birds have four Toes in each foot, three standing forwards, and one backwards. Some few have only three, all standing forwards, for these want the back-toe’.[1]

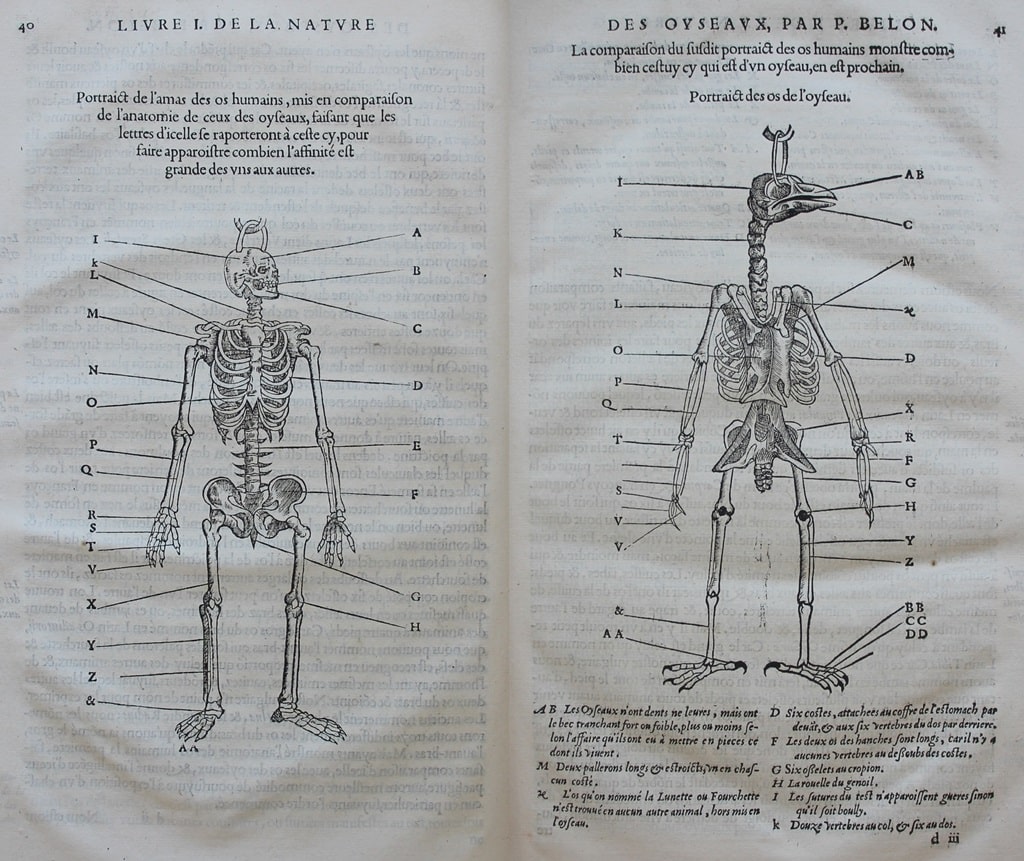

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), pp 40–41: Belon’s comparison of the skeleton of a human and a bird.

This image of a comparison of the skeleton of a bird with that of a human is striking; when it was first printed in 1555 it would have been controversial. As Arbel argues, Belon’s decision to juxtapose the skeletons of a bird and a human and to make the skeleton of the former the same height as the latter was a subtle method of undermining the age old suggestion that birds (and animals more generally), were subservient to human beings.[2] In the Book of Genesis 1: 26 mankind was given ‘dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth’, and Aristotle (384–322 BC), had drawn attention to the rational nature of mankind, comparing it with non-rational animals.[3] Belon seemed to be suggesting an alternative view.

Belon was clearly aware of the power of the image and its ability to relate in a graphic way (in every sense), his principal point – that the skeletons of birds and man had much in common. He argued that:

If you examine the wing, the thigh, the leg and the foot of a bird, and compare them to a four-footed animal or to a man, you will discover a correspondence between the bones in nearly every case. The heels of a human being who walks on the tip of his fingers would be located above all the bones of his foot, and likewise all four-footed animals, when walking on the tips of their fingers. But in order to demonstrate this experiment in a way that would be understood by every peasant without wasting time on the description of members, we shall indicate each bone, comparing it to those of other animals and Man … [Here] we shall only make the comparison between the human bones and those of birds …[4]

Belon makes his point subtly and, as Arbel argues, he ‘leaves his readers to reach the conclusions that arise from his text and illustrations, which might be associated with classical and Renaissance works that called into question the prevailing ideas about the human-animal divide’.[5] He could do so because his observations were based on his wide experience of dissecting birds for he noted that: ‘No bird has fallen into our hands without its undergoing an anatomical examination when it was possible to make one. Thus we have examined the internal structures of 200 different species of birds. So it is not strange that we are able to describe and figure the bones of birds in such as exact fashion’.[6]

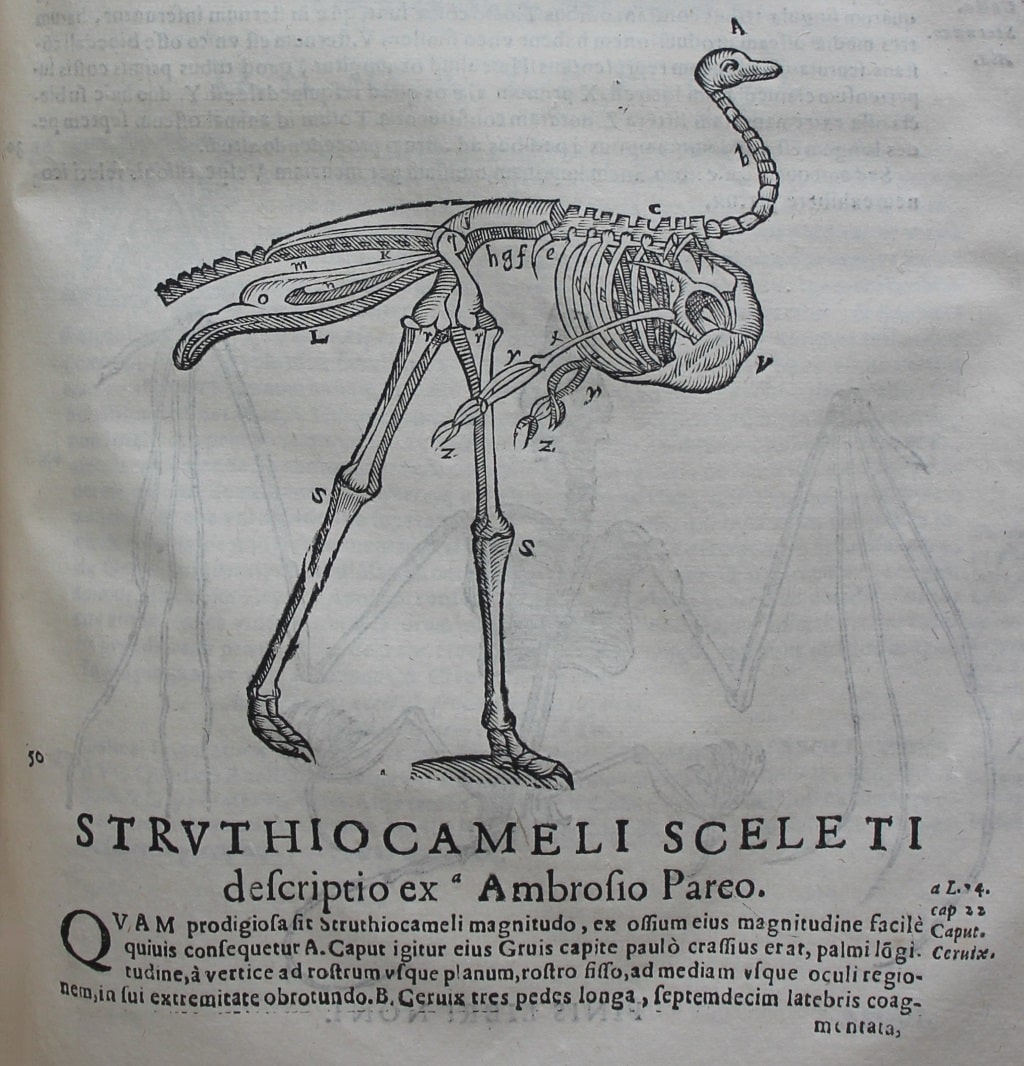

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1646), i, p. 597: skeleton of an ostrich.

Belon was not the first comparative anatomist – as Gudger suggests, one could argue that the discipline began with Aristotle – but his striking image would live on in later works.[7] While the great Italian natural historian Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), did not include it in the first edition of his three-volume work on ornithology, his subsequent editor Bartolomeo Ambrosini (1588–1657), chose to use it in his 1642 edition of Aldrovandi’s Monstrorum historia: cum paralipomenis historiæ omnium animalium. Bartholomæus Ambrosinus … labore, et studio volumen composuit; Marcus Antonius Bernia in lucem edidit (Bologna, 1642). As Edward Worth (1676–1733), possessed the Ambrosini edition, he was the proud possessor of not one but two copies of this famous image! Aldrovandi’s three volumes on birds likewise reflected his own experiments in avian dissection and he not only included wonderful images of the skeleton of a parrot and swan, but also a discussion of the anatomy of an ostrich and an eagle.[8]

Ostrich, Struthio camelus Linnaeus, 1758, NMINH:2003.41.1. © NMI

The text underneath Aldrovandi’s image of a skeleton of an ostrich makes it clear that he owed his image to the famous French surgeon, Ambroise Paré (1510–90), whose works were also collected by Worth. Aldrovandi drew particular attention to the ostrich’s long neck (estimated to be about three-foot long), and pointed to its seventeen vertebrae. He was especially impressed by the size of the ostrich’s bones – he compared the size of its skull to that of a crane but found it to be thicker.[9] In all the total skeleton of the ostrich was seven foot long![10]

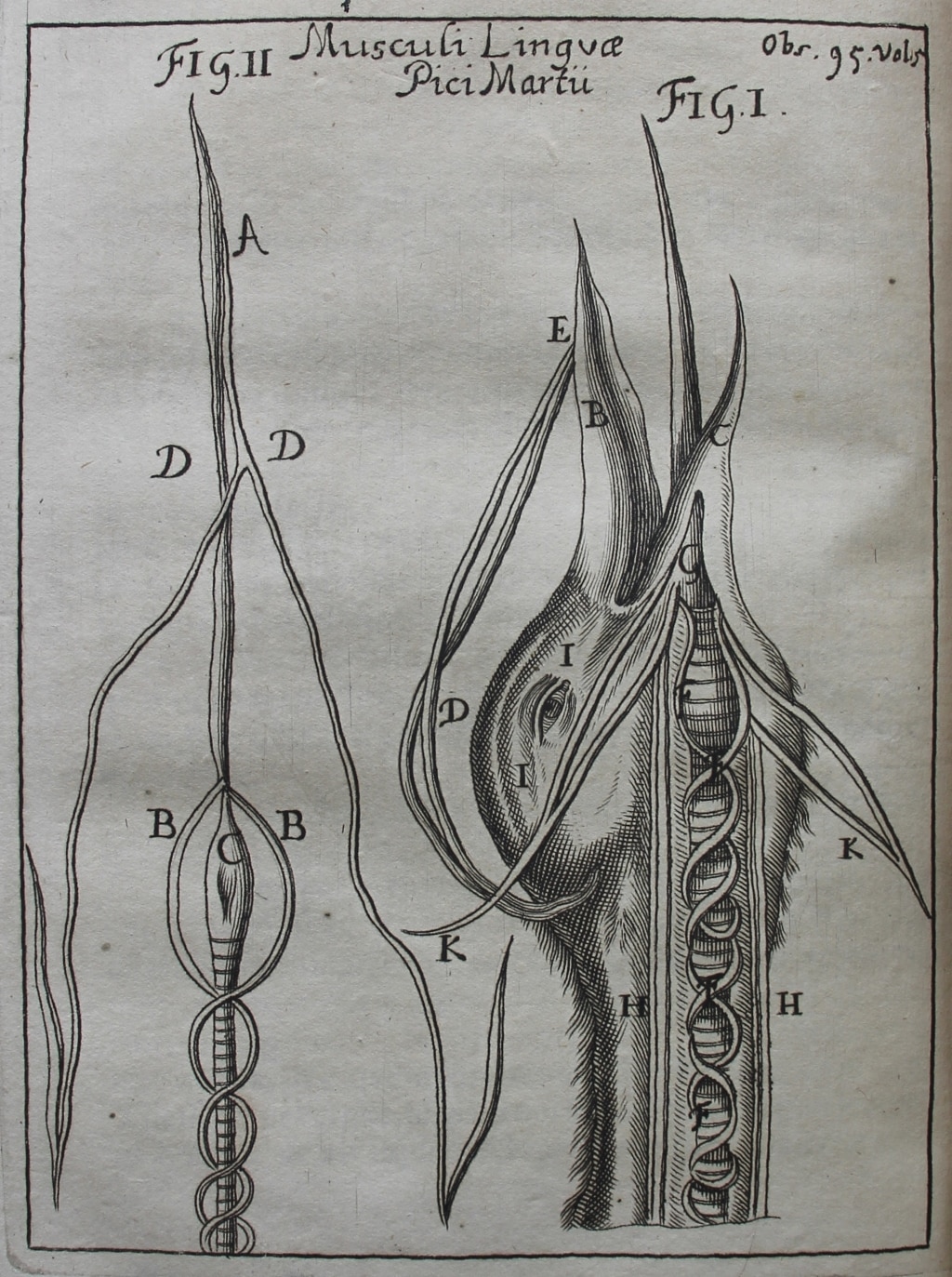

Thomas Bartholin, Acta medica & philosophica Hafniensia ann. 1671-[1679] (Copenhagen, 1673–79), ii, plate facing p. 249: muscles of the tongue of a woodpecker.

Given a dearth of human cadavers, dissection of animals formed an important part of anatomical education in early modern Europe. One of the most important authors in the history of early modern anatomy was the Danish anatomist Thomas Bartholin (1616–80), who came from a famous family of physicians who dominated the teaching of anatomy in Copenhagen for well over a century. Thomas was perhaps the most famous of them all and he is known for a host of discoveries, not least his exploration of the lymphatic system in both humans and dogs. He did not, however, limit his dissections to canines and in this plate he demonstrated his dissection of the muscles of a tongue of a woodpecker? Why a woodpecker? Because, as Heisman notes, woodpeckers have extraordinarily long tongues![11]

Great Spotted Woodpecker; Newcastle, Wicklow (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Van Grouw explains the reason why they need them and their extent:

In most birds the tongue cannot be extended beyond the tip of the bill, but woodpeckers, among others, are an exception. Their long tongue, tipped with various barbs or bristles and coated with sticky saliva from a well-developed salivary gland at the base of the jaw, can be shot out rapidly to trap insects. It’s all achieved by the action of the muscles surrounding the flexible and whip-like hyoid horns. But the horns do need to be considerably longer than those of other birds. So long are they in some species that they meet at the back of the head, extending right over the top of the cranium along a channel in the skull and even twirl around the right eyeball or plunge into the right nostril.[12]

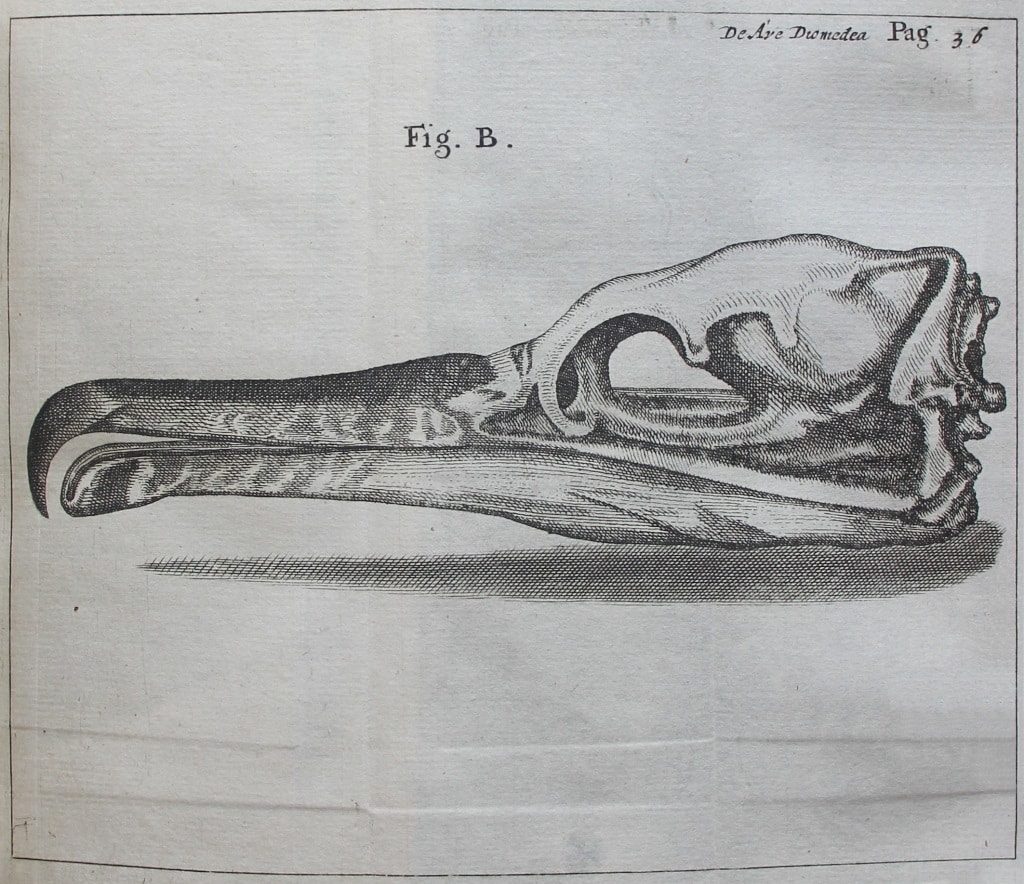

Francesco Redi and Friedrich Lachmund, Opusculorum pars prior; sive, Experimenta circa generationem insectorum … Accedit J. Frid. Lachmund De ave Diomedea dissertatio (Amsterdam, 1686), ii, foldout plate facing p. 36: skull of ‘Ave Diomedea’.

And finally we have the mysterious ‘Ave Diomedea’ of Friedrich Lachmund, whose treatise De ave Diomedea dissertatio is appended to a much larger work by the Italian natural historian Francesco Redi (1626–97). Lachmund (1635–76), had written his treatise in the form of an epistle, in this case to John Daniel Major (1634–93), a professor of anatomy and botany at the University of Kiel, and an authority on collecting. In it he included this interesting plate which depicts, among other things, the skull of the ‘Ave Diomedea’. Lachmund (writing in 1672), related that he had been sent the bird two years previously and in attempting a literature search had found little useful about it – even Aldrovandi, though he had discoursed on the bird, had included an erroneous image of it. Lachmund intended to rectify this by presenting Major (and his readers), with a correct image and an introduction to the bird.

But what was this strange bird? Lachmund’s treatise was about an albatross but the skull in the image has more similarities with that of a cormorant, though it appears to be missing the extra bone which projects from the back of a cormorant’s skull.[13] As Van Grouw notes, this bone was important because it allowed the cormorant’s long jaw to keep hold of their prey, necessary because the sides of the cormorant’s bill were not serrated and though the tip of the bill was hooked it was not sufficiently strong to keep hold of a struggling prey – such as a desperate fish struggling for its life![14] As Willughby and Ray remind us, ‘The Bill in Birds hath two principal uses; the one as an instrument to gather and receive their food; the other as a weapon to fight with, either by assaulting others, or defending and revenging themselves.’[15] Clearly Lachmund thought he had found something new – new enough to add to his cabinet of curiosities and to boast about in print to none other than Major, the founder of museology![16] As Keller notes, by publicly addressing Major Lachmund not only drew attention to his own collections but hoped to stimulate research into a rare bird.[17] Thus the early modern fixation with cabinets of curiosities not only reflected the interest of individual collectors in bird anatomy but also served to facilitate research by later ornithologists.

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Arbel, Benjamin, ‘The beginnings of comparative anatomy and Renaissance reflections on the human-animal divide’, Renaissance Studies, 31, no. 2 (2017), 201–222.

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Clifton, James, ‘Kunst und Naturalien Kammern of Seventeenth-Century Naples: Johann Daniel Major’s view from Germany’, in Gianfrancesco, Lorenza, and Neil Tarrant (eds), The Science of Naples: Making Knowledge in Italy’s re-eminent city, 1500–1800 (London, 2024).

Gudger, E. W., ‘Some early and late illustrations of comparative osteology’, Annals of Medical History, 1, no. 3 (1929), 334–55.

Heisman, Rebecca, ‘The Amazing Secrets of Woodpecker Tongues’, American Bird Conservancy, 10 June 2021 online blog.

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

Keller, Vera, Curating the Enlightenment: Johann Daniel Major and the Experimental Century (Cambridge, 2024).

Van Grouw, Katrina, The Unfeathered Bird (Princeton and Woodstock, 2013).

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), pp 2–3. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[2] Arbel, Benjamin, ‘The beginnings of comparative anatomy and Renaissance reflections on the human-animal divide’, Renaissance Studies, 31, no. 2 (2017), 220.

[3] Ibid., 202.

[4] Translated in ibid., 219.

[5] Ibid., 221.

[6] Gudger, E. W., ‘Some early and late illustrations of comparative osteology’, Annals of Medical History, 1, no. 3 (1929), 337.

[7] Ibid., 334.

[8] Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1646), i, pp 643–4 (parrot skeletons), 122 (eagle skeleton); iii, pp 9–15 (swan skeleton and organs).

[9] Ibid., i, p. 597.

[10] Ibid., p. 598.

[11] Heisman, Rebecca, ‘The Amazing Secrets of Woodpecker Tongues’, American Bird Conservancy, 10 June 2021 online blog.

[12] Van Grouw, Katrina, The Unfeathered Bird (Princeton and Woodstock, 2013), p. 79.

[13] Clifton, James, ‘Kunst und Naturalien Kammern of Seventeenth-Century Naples: Johann Daniel Major’s view from Germany’, in Gianfrancesco, Lorenza, and Neil Tarrant (eds), The Science of Naples: Making Knowledge in Italy’s re-eminent city, 1500–1800 (London, 2024), p. 173. I am very grateful to Dr James Maxwell, NMI, for identifying this bird!

[14] Van Grouw, The Unfeathered Bird, p. 144.

[15] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 1.

[16] On Major see Keller, Vera, Curating the Enlightenment: Johann Daniel Major and the Experimental Century (Cambridge, 2024).

[17] Ibid., p. 310.