Flightless Birds

Flightless birds were a source of deep fascination for early modern writers. Some, such as ostriches, had been known for centuries, but others, encountered on expeditions to South America and Asia, needed to be fitted into known frameworks of understanding.

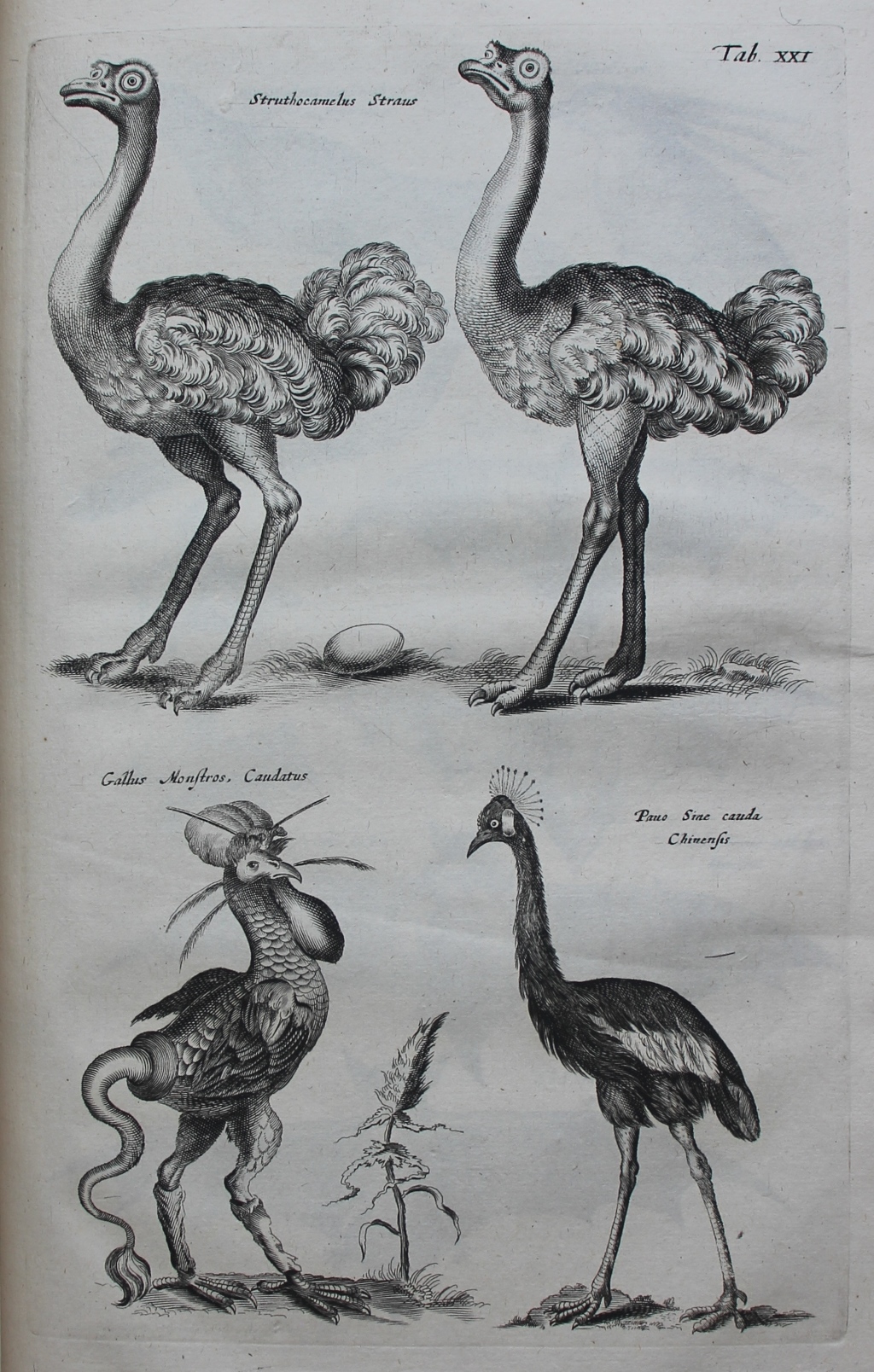

Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), plate XXI: two ostriches, Aldrovandi’s monstrous bird and Chinese peacock.

We see this tendency in Joannes Jonstonus’s commentary on the above image of ostriches in Worth’s copy of Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657). Jonstonus (1603–75), carefully references Aristotle’s Book IV, in which Aristotle had provided what one might call the quintessential definition of a flightless bird (in this case ‘the Libyan ostrich’):

Much the same may be said also of the Libyan ostrich. For it has some of the characters of a bird, some of the characters of a quadruped. It differs from a quadruped in being feathered; and from a bird in being unable to soar aloft and in having feathers that resemble hair and are useless for flight. Again, it agrees with quadrupeds in having upper eyelashes, which are the more richly supplied with hairs because the parts about the head and the upper portion of the neck are bare; and it agrees with birds in being feathered in all the parts posterior to these. Further, it resembles a bird in being a biped, and a quadruped in having a cloven hoof; for it has hoofs and not toes. The explanation of these peculiarities is to be found in its bulk, which is that of a quadruped rather than that of a bird. For, speaking generally, a bird must necessarily be of very small size. For a body of heavy bulk can with difficulty be raised into the air.[1]

Jonstonus depicted his ostriches like two dancers, and provided his readers with a generic (albeit engaging) description:

The Ostrich, hath a small head like a Goose, not covered with feathers, with cloven feet, Aristot. 4. hist. He is too big to fly, yet sometimes he runs swiftly, the wind entring under his wings, and extending them like sails. It is certain he will out-run a man on horseback. He is a fruit-eater. He will swallow small pieces of bones and stones greedily, but he casts them out again; also pieces of Iron. How should he digest them, for a Lion that is hotter cannot? He makes a nest of sand, that is low and hollow, and fenceth it against the rain. She layes above 80 eggs: yet the young ones are not all hatcht at the same time; The eggs are very great, as big as a young Childs head, weighing about 15 pounds, they are extream hard, and the shell is like stone. The young are bred of them by heat of the Sun; some, because they saw this Bird looking on them, thought the young ones to be hatcht by her eye: She is wonderfull simple; when she hides her neck in a bush, she thinks she is all hid.[2]

Beneath Jonstonus’s ostriches are depicted Aldrovandi’s monstrous freak rooster and what Jonstonus calls a ‘Chinese peacock’. Jonstonus’s inclusion of Aldrovandi’s freak rooster, which he claimed to have seen in the palace of Francesco I de’ Medici (1541–87), Grand Duke of Tuscany (and which is discussed in our Aldrovandi exhibition), is yet another indication of his reliance on Aldrovandi’s encyclopaedic work, while the inclusion of a ‘Chinese peacock’ reflects Jonstonus’s rather haphazard arrangement of material, for peacocks, like roosters, though they seldom fly, are capable of flight.

Charles de L’Ecluse (Carolus Clusius), Exoticorum libri decem: quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiæ describuntur: item Petri Bellonii observationes eodem Carolo Clusio interprete (Antwerp, 1605), p. 98: ‘Emeu avis’: cassowary.

Writing in 1605 the Flemish physician and botanist Carolus Clusius (1526–1609), provided one of the most extensive descriptions of what he called an ‘emeu’. It was one to which Francis Willughby (1635–72) and John Ray (1627–1705), resorted when they wanted to give their readers ‘a more full and accurate description of all its parts’, for they were aware that Clusius’s description formed the basis of all later descriptions.[3] Clusius declared that he believed that ‘this sort of Bird is not peculiar to the Molucca Islands, but found also in Sumatra or Taprobane, and the neighbouring Continent to those Islands’.[4] He provided his readers with a lengthy description:

This Bird (saith he) as it walked, holding up its head, exceeded the height of four foot by some inches: For the Neck from the top of the Head to the beginning of the Back was almost thirteen inches long; the body two foot over; the Thighs with the Legs to the bending of the Feet seventeen inches long. The length of the body it self from the Breast to the Rump was almost three foot. The feathers covering the whole body, with those on the lower part of the Neck next to the Breast and Belly, and the Thighs were all double, two coming out of the same small short pipe or hose, and lying the one upon the other; the upper being somewhat the thicker or grosser, the nether the more fine and delicate: They are also of a different length, as I observed in the case of the like Bird. For those on the lower part of the Neck were shorter; those on the middle of the body and sides longer (viz. of six or seven inches:) But those on the extreme or hind-part of the body about the Rump (for it wanted the Tail) nine inches long, and harder than the rest. Although they are all hard or stiff, yet are they not broad but narrow, with thin-set filaments opposite one to another on each side; of a black colour, but about the Thighs tending to cinereous, the shaft only remaining black, as in the rest. These feathers had that form and situation, that to those that behold the Bird afar off, its skin might well be thought to be covered not with feathers, but only with hairs, seeming like to a Bears; and to want Wings; though indeed it had Wings, lying hid under the feathers covering the sides, furnished with four greater feathers of a black colour, as I observed in the case, though they were so broken at the tops, that I could determine nothing certainly concerning their length. But their broken shafts were pretty thick, hard and solid, and ran deep down into the outmost part of the Wing. The upper part of the Wing next the body had its covert feathers like those on the Breast. For it is to be thought, that this kind of Wings are given to this Bird to assist her and promote her speed in running: For I believe she cannot fly, nor raise her self from the earth.[5]

Cassowary, Casuarius casuarius (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:2003.41.4.

© NMI

As Willughby and Ray noted, Clusius might have been more definite about the inability of the bird to fly![6] That Clusius was describing a cassowary is clear from his discussion of its casque – though he considered it to be formed of feathers: ‘The upper Chap of the Bill was as it were arched or bent like a Bow, a little above the point perforate with two holes, serving for Nosthrils; from the middle whereof, reaching to the top of the Head, arises a kind of towring Diadem or Crown, of a horny substance, near three inches high, of a dusky yellow colour; which, as I understood, falls off at moulting time, and grows up again with the new feathers’.[7]

Clusius’s use of the word ‘Emeu’ in this context may sound confusing since emus, native to Australia, were unknown in Europe at that time, whereas the first cassowary had reached Europe by 1597.[8] The Dutch merchant seaman Cornelis de Houtman (d. 1599), who led the first Dutch expedition to Java, brought back a cassowary to the Netherlands in 1597 and the event was later described by one of the Dutch naval officers, Willem Lodewycksz in his Historie van Indien (Amsterdam, 1617).[9] The bird had been given to Ernest of Bavaria (1554–1612), archbishop of Cologne, by Count Georg Eberhard of Solms (1563–1603), and Clusius had an opportunity to examine a painting of it owned by the Count’s widow, Countess Sabine of Egmond (1562–1614).[10] As Jolyon C. Parish notes, cassowaries and dodos were also confused throughout the early modern period.[11] The word ‘emu’ or ‘ema’ was used because it simply meant ‘big bird’, which the cassowaries undoubtedly were!

Willem Piso’s commentary on Jakob de Bondt’s ‘Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex’ in Willem Piso, De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), p. 71: ‘De Emeu, vulgo Cassoaris’.

The same confusion in nomenclature is evidently in the Dutch physician Jakob de Bondt’s Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex which Willem Piso (1611–78), included in De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658). The latter text, which brought together the results of explorations of the territories colonized by both the Dutch West and East India Companies, was a seminal work of natural history and it included images of a number of flightless birds: a cassowary from the island of Seram in Indonesia, a Rhea Americana from the northwest region of Brazil, and perhaps the most famous of all flightless birds, the dodo of Mauritius, now extinct.

Its origin was the Historia Naturalis Brasiliae by the Dutch physician Willem Piso and the German polymath Georg Marcgraf (1610–c. 1643/4), which Whitehead has argued ‘is the most important early account of Brazilian zoology’ and few would challenge this assertion.[12] Both Piso and Marcgraf had travelled to Brazil in the retinue of Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen (1604–79), who ruled as Governor General of Dutch Brazil between 1637 and 1644. The count was a keen supporter of all things scientific and employed both Piso and Margraf, along with others, to document the flora and fauna of Brazil.[13] Whitehead notes that Marcgraf’s descriptions would subsequently inform at least 38 names assigned to Brazilian birds by Carl Linnaeus (1707–78).[14]

Count Johan Maurits had been sent to Brazil on behalf of the Dutch West India Company (WIC), and he arrived in Recife in early 1637. While Piso and Marcgraf were not the only members of Johan Maurit’s court to take a keen interest in documenting in text and image what they encountered, the publication of Historia Naturalis Brasiliae in 1648 made their names in the scientific circles of early modern Brazil and Europe. Piso was responsible primarily for four books on the medicines of Brazil, while Marcgraf’s eight books covered areas such as botany and zoology. Alongside this monumental text were related watercolours which Count Johan Maurits subsequently sold to the Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg (1620–88).[15]

The success of Piso’s 1648 publication of Historia Naturalis Brasiliae in turn led him to republish it in 1658. The title of the 1658 edition (which Worth owned), reflected the fact that the later edition now included records not only from Dutch West India Company colonies in Brazil, but also from lands colonized by the Dutch East India Company in Indonesia. By combining these two works Piso could justifiably promote his new 1658 text as a natural history of the two Indies.

Jacob de Bondt (1592–1631), had been sent to Indonesia by the Dutch East India Company as part of their attempt to source new medicines and, like Piso, he did not limit his researches to the medicines of the areas colonized by his patrons. In his dedication of another work, his De Medicina Indorum (Leiden, 1642), he emphasized that his text was based on his own research, not hearsay, and he took the same approach to his examination of the birds of Indonesia. As the subtitle of his Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex in Piso’s 1658 compilation makes clear, much of his focus in the text (which had not previously been printed), was on medicine, but in Book V, he included his findings on the animals he encountered in Indonesia and in the above image, we see his picture of what he calls ‘De Emeu, vulgo Cassoaris’.

In his description De Bondt gives us the location of where he sighted the bird: the island of Seram, in the Maluku province of Indonesia; and its proportions: with its head held high it was up to five feet. While he noted that it had some similarities to an ostrich it also differed from them in a number of ways, for it had more toes than an ostrich which only had two. Crucially De Bondt drew attention to a horn-like structure (the casque), which ran from the head to the back of the neck, and this is depicted in the accompanying image, which makes it clear that what De Bondt was actually encountering was a cassowary.[16] It was, as De Bondt noted, ‘not counted among flying birds’ due to its wings which, though they enabled the bird to run, did not allow it to fly.[17]

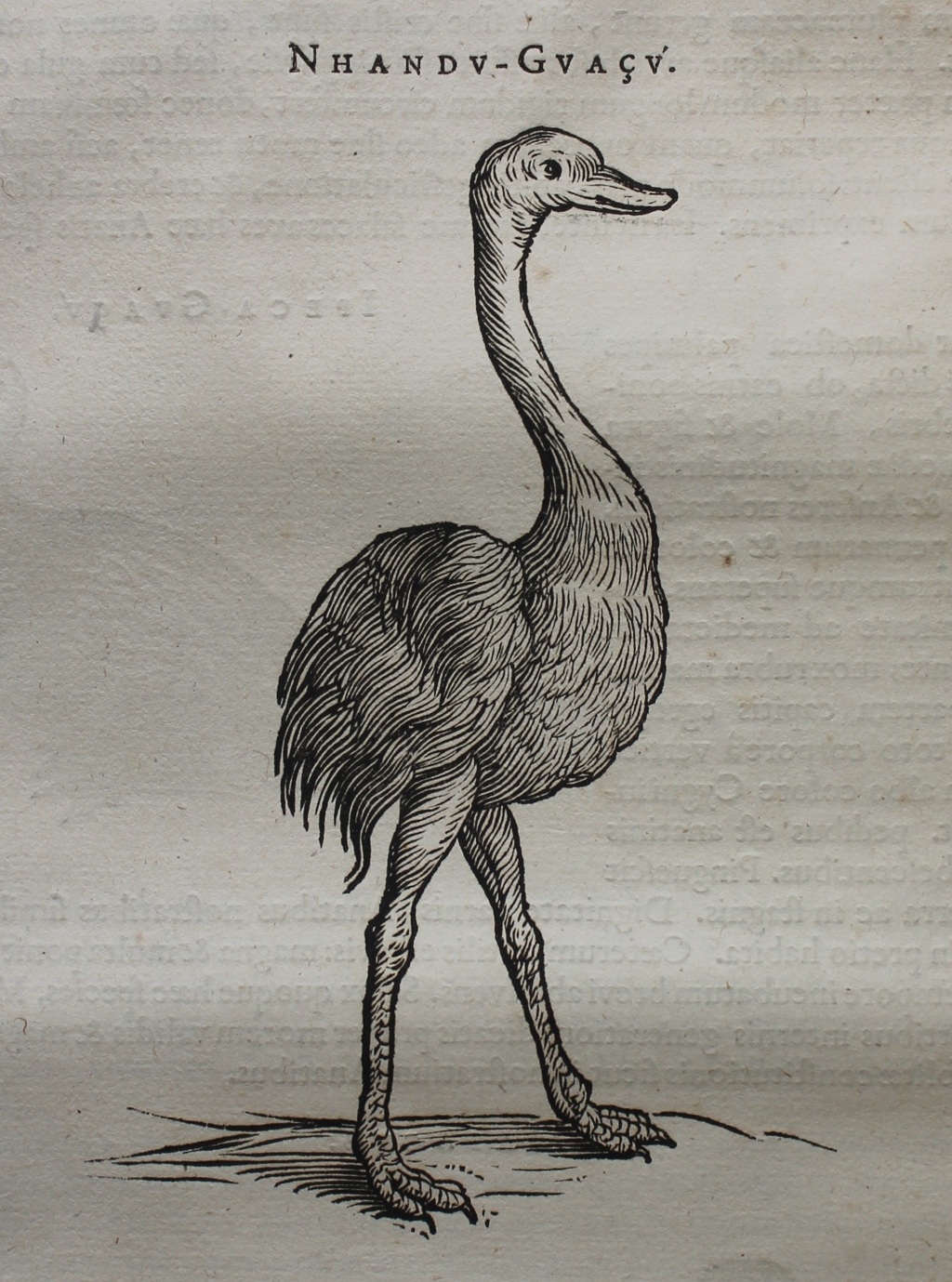

Willem Piso, De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), p. 84: Rhea.

The Brazilian section of Worth’s copy of De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), includes a discussion of a distant cousin of ostriches, cassowaries and emus: the Rhea Americana. The original of the above image was sighted in Brazil in the mid seventeenth century and described as follows:

Nhanduguaçu in Brazilian, Ema in Portuguese. An ostrich. They are in this country very large but somewhat smaller than the African. Their legs are long, the foot measures about one and a half feet, the shank one foot. They have three front toes with black, thick, and completely blunt claws. There is one rear toe, but it is round and thick, so that on slippery ground or on a plank surface they walk only with difficulty and fall easily. The neck is held curved like that of a swan or a stork; it is about two feet long. The head is gooselike; they have handsome black eyes and a not very broad flat beak, two and a half fingers long. The wings are small and useless for flight, but when they raise one like a sail they increase their running speed so much that they can rarely or never be overtaken by a hunting dog. The feathers on the whole body are as gray as on a crane; they are longer and more beautiful on the back, and the whole feathered part of the body appears almost round. It does not have the tufted tail usually pictured [that is, for the African bird]; rather the feathers reach over the whole length of the back as far as the rump. Counters and other iron objects it swallows easily but cannot digest, passing them undamaged through the anus. It lives on fruit and meat. It is common in the campos of Sergipe and Rio Grande, but does not occur in Penambuco.[18]

Exactly who sighted and drew the bird has been a matter of contention since the seventeenth century, for despite Willem Piso’s claims in Worth’s copy of De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), it seems likely that the real credit should go to his collaborator Georg Marcgraf, who has rightly been described as ‘the father of Brazilian natural history’.[19]

In Piso’s 1648 text, published some years after Marcgraf’s death, the former had claimed that Marcgraf had essentially acted as Piso’s servant and that the credit for this ground-breaking book should be Piso’s alone. By the time Piso produced his enlarged second edition, De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica (Amsterdam, 1658), he had gone so far as to take Marcgraf’s name off the title page (the omission is visible on the ‘Dead Dodos’ webpage). This interpretation of Marcgraf’s role was vehemently challenged by Marcgraf’s younger brother, Christian (1622–87), who provides us with a brief but punchy ‘life’ of his elder brother, liberally castigating Piso for his ‘forgettfullness, boldness, & vanity’, and lauding his brother.[20] Worth would have been familiar with the controversy for the Latin version of Christian’s ‘life’ of his brother was included in Worth’s copy of Jean-Jacques Manget’s Bibliotheca scriptorium medicorum (Geneva, 1731). Christian’s ‘life’ of his adored elder brother is undoubtedly biased in the latter’s favour but it is striking that Marcgraf’s texts were written in a code, a code which he did not share with his younger colleague, the ambitious Piso.[21]

Marcgraf’s duties led him to complete several journeys around Brazil, during which he mapped not only the land but also the plants, animal and bird life of the territories through which he passed. He was keen to emphasise that his information was a result of direct eye-witness testimony, and he stressed the point in his dedication of the work to his patron, Count Johan Maurits:

To Johann Maurice, Count of Nassau, great chief of the lands and seas of Brazil, Georg Margrave of Liebstadt, a German of Saxony, dedicates these things, which during his travels through Brazil, he with indefatigable zeal inquired not, described accurately, and made figures of from the life, sought out their names among the natives, and so far as he was able when opportunity offered, investigated their uses, and in his history has arranged them for the use of all students and admirers of natural sciences, in due acknowledgment and as a sign of gratitude for the greatest kindnesses received from him.[22]

It was a point emphasised also by his editor, Johannes de Laet (1581–1649), in his preface to the work and, as Smith argues, throughout the work Marcgraf is represented as someone who is directly observing nature, rather than viewing it through the lens of earlier authorities.[23] Likewise the structure of the work owed little to earlier encyclopaedic authorities such as Conrad Gessner (1516–65) or Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), whose systems of classification would also have been familiar to Edward Worth (1676–1733).[24] As Smith notes, Marcgraf was interested in three things: a discussion of bird names; a detailed description of a bird he had seen; and, finally, a short note on the bird’s uses for humans.[25]

Marcgraf not only acted as a commentator and illustrator of Brazil’s flora and fauna: he was also Count Johan Maurit’s cartographer and astronomer. As cartographer he was charged with mapping the territories claimed by the Dutch West India Company (WIC), and, as Brienen notes, his map of Brazil would later be lauded by Caspar Barlaeus (Caspar van Baerle, 1584–1648), as ‘one of the many important achievements of Johan Maurit’s governorship’.[26] This reminds us that Marcgraf’s scientific explorations and his mapping of newly conquered territories were regarded by Count Johan Maurits as two-sides of the same coin: as Brienen rightly suggests, Marcgraf’s expeditions, accompanied as he was by hundreds of soldiers, were ‘probably not made in the pure interest of science, but were rather intended to further the WIC’s colonisation of Brazil’.[27] As Smith argues, even the naming of birds may be seen as part of an act of appropriation for while Marcgraf began with the indigenous name, he was quick to link it to a name more familiar to his European readers.[28] In the case of the Rhea Americana he chose a Portuguese name, but he would also liberally use Dutch or German names – possibly also in an attempt to aid his European reader imagine the bird in question.[29] While we cannot track all of Marcgraf’s journey’s through Brazil, it seems likely that he encountered the above rhea, which he terms a struisvogel (ostrich), in Ceará, a state in north-western Brazil.[30]

As the above description of a Rhea Americana demonstrates, Marcgraf provided first-hand commentaries on the birds he saw and while the woodcuts which accompanied his texts were in a rather naïve style, the scientific information he provided ensured that the Historia naturalis Brasilia (Leiden and Amsterdam, 1648), ruled supreme not only because it was the ‘earliest published natural history of Brazil’, but also due to the utility of its scientific descriptions of Brazil’s flora and fauna.[31] As we shall see, Piso’s controversial 1658 edition would later be mined by English natural historians Francis Willughby and John Ray.[32]

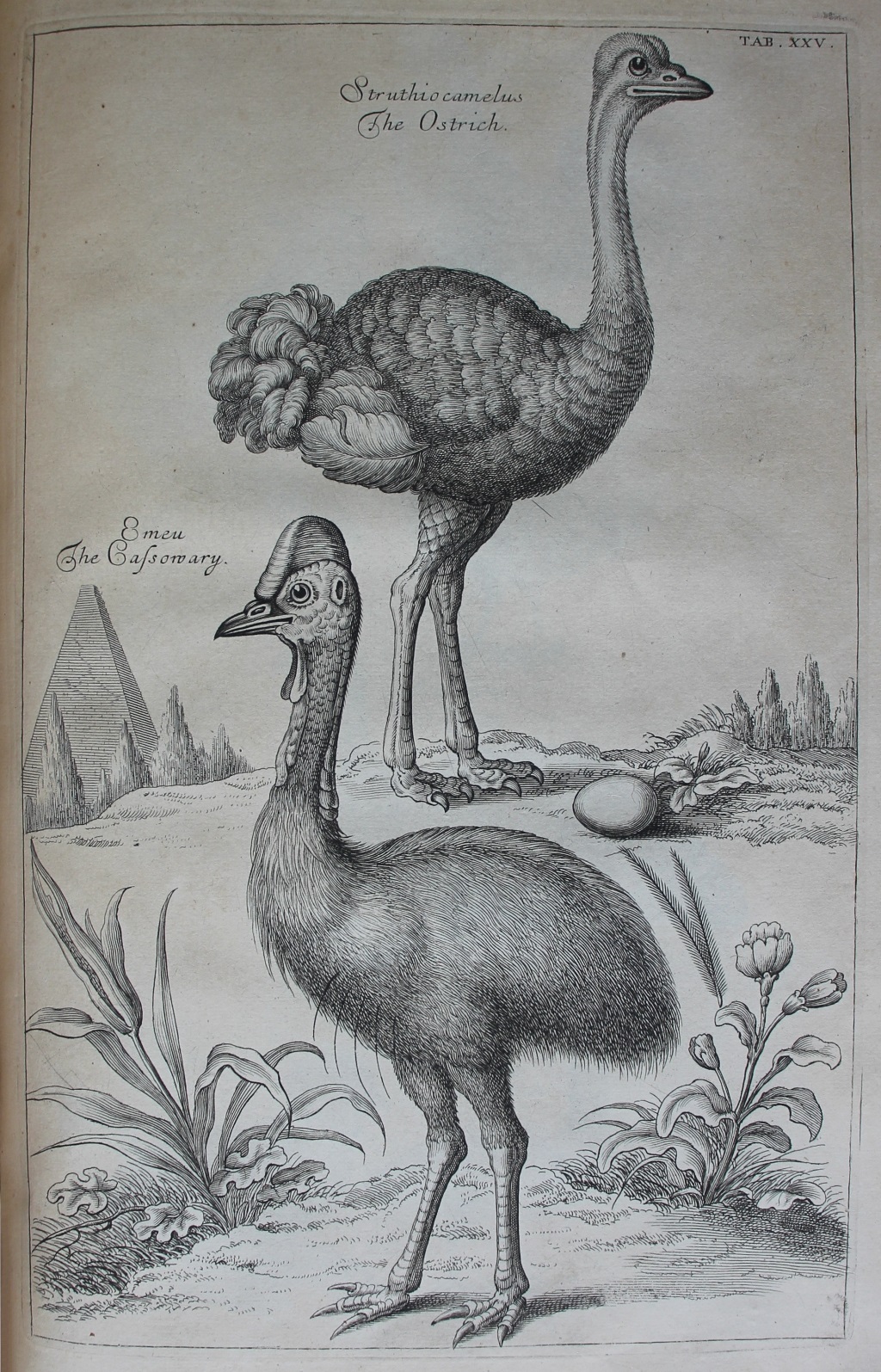

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XXV: ‘Ostrich and Emu/Cassowary’.

Willughby and Ray make their debt to earlier commentators clear in the title of their sections on ostriches, emus/cassowaries and rheas: in the note on ostriches they begin by advising their readers to look at what Ulisse Aldrovandi, and Conrad Gessner, have said about the bird and they then proceed to discuss the ‘American ostrich’ of Marcgraf. Concerning cassowaries, they provide their key sources: ‘The Cassowary or Emeu of Aldrovandus, Clusius, Nierembergius, Bontius and Wormius’. Depicted in the above image is an ostrich on top, and a cassowary, with its typical casque, displayed beneath. In the background of the cassowary we can see pyramids – Willughby and Ray’s attempt to indicate their exotic nature.

Ostriches had, as they note, been well known since the time of Pliny the Elder (23/4–79), and they mention that ostrich feathers were still very much in use in ladies fans.[33] Their description of ostriches, while detailed, indicates that it was not from eye witness testimony for their declare that: ‘The Eyes are great, with hazel-coloured Irides. Of all great birds this alone hath both Eye-lids [upper and lower] as Pliny witnesseth. Which whether it be true or not we leave to be examined by others that have opportunity of seeing the bird’.[34] They repeat Jonstonus’s suggestion that ostriches were capable of swallowing iron but concentrates on a morphological description of the bird.

They say rather more about cassowaries, possibly because here they felt on firmer ground, having seen the birds for themselves: ‘We have seen four birds of this kind at London; three Males, and one Female: viz. one Male among his Majesties birds kept in St. James‘s Park near Westminster; two Males and a Female at Mr. Maydstons, an East-India Merchant in Newgate-Market, brought out of the East Indies’.[35] The description they give begins with the chief defining characteristic of cassowaries:

It hath a horny Crown on the top of the Head. The Head and Neck are bare of feathers, only thin-set with a hairy down. The skin is of a purplish blue colour, excepting the lower part of the backside of the Neck, which is red, [or of a Vermilion colour.] In the lower part of the Neck hand down two Wattles or Lobes of flesh as low as the Breast. It hath a very wide mouth. The Bill is near four inches long, of a moderate thickness, and streight. The Legs are thick, and strong. It hath three Toes in each foot, all standing forward, for it wants the back-toe. The Claw of the outmost Toe is much longer than the rest. It hath some rudiments of Wings rather than Wings, consisting of only five naked shafts of feathers, somewhat like Porcupines quils, having either no Webs and feathery parts, or which were in the Bird we described broken and worn off. It hath no Tail; a great body invested with blackish or dusky feathers, of a rare texture, which to one that beholds the Bird at a distance seem rather to be hairs than feathers’.[36]

Despite their scientific rigour they included the idea that cassowaries were ‘Avis ignem devorans’: birds which could eat live coals![37]

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aristotle, ‘On the Parts of Animals: Book IV’. Translated by William Ogle, Chapter 14.

Brienen, R. P., ‘Georg Marcgraf (1610–c. 1644): A German Cartopgrapher, Astonomer, and Naturalist-Illustrator in Colonial Dutch Brazil’, Itinerario, 25, no. 1 (2001), 85–122.

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

Kusukawa, Sachiko, ‘The role of images in the development of Renaissance natural history’, Archives of Natural History, 38, no. 2 (2011), 189–213.

MyClymont, James R., ‘The etymology of the name ‘Emu’, readbookonline.net archived on Wayback Machine.

Paris, Jolyon C., The dodo and the solitaire: a natural history (Bloomington, Indiana, 2013), kindle edition.

Pires-O’Brien, Maria Joaquina, ‘An essay on the history of natural history in Brazil, 1500-1900’, Archives of Natural History, 20, no. 1 (1993), 37–48.

Schreiber, Arnd, ‘Historical ostriches in the Libyan Desert, with ecological and taxonomic considerations’, Natural History Sciences. Atti Soc. it. Sci. nat. Museo civ. Stor. nat. Milano, 11, no. 2 (2024), 45–64.

Smith, Paul J., ‘Marcgraf’s Fish in the Historia Naturalis Brasiliae and the Rhetorics of Autoptic Testimony’, in Françozo, Mariana (ed.), Toward an Intercultural Natural History of Brazil: The Historia Naturalis Brasiliae Reconsidered (New York, 2023), pp 122–141.

Whitehead, P. J. P., ‘The original drawings for the Historia naturalis Brasiliae of Piso and Marcgrave (1648)’, Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History, 7, no. 4 (1976), 409–22.

Whitehead, P. J. P., ‘The biography of Georg Marcgraf (1610-1643/4) by his brother Christian, translated by James Petiver’, Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History, 9, no. 3 (1979), 301–14.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Aristotle, ‘On the Parts of Animals: Book IV’. Translated by William Ogle, Chapter 14. On Aristotle and Libyan ostriches see Schreiber, Arnd, ‘Historical ostriches in the Libyan Desert, with ecological and taxonomic considerations’, Natural History Sciences. Atti Soc. it. Sci. nat. Museo civ. Stor. nat. Milano, 11, no. 2 (2024), 52.

[2] Quotation from contemporary 1657 translation: Joannes Jonstonus, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657), p. 191.

[3] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books … (London, 1678), p. 152. Worth did not own the English edition.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p. 151.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., p. 152.

[8] Paris, Jolyon C., The dodo and the solitaire: a natural history (Bloomington, Indiana, 2013), kindle edition suggests 1598 but MyClymont, James R., ‘The etymology of the name ‘Emu’’, argues that the date was 1597.

[9] Edward Worth did not own this work.

[10] Kusukawa, Sachiko, ‘The role of images in the development of Renaissance natural history’, Archives of Natural History, 38, no. 2 (2011), 197.

[11] Paris, The dodo and the solitaire: a natural history, kindle edition.

[12] Whitehead, P. J. P., ‘The original drawings for the Historia naturalis Brasiliae of Piso and Marcgrave (1648)’, Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History, 7, no. 4 (1976), 409.

[13] Brienen, R. P., ‘Georg Marcgraf (1610-c. 1644): A German Cartographer, Astronomer, and Naturalist-Illustrator in Colonial Dutch Brazil’, Itinerario, 25, no. 1 (2001), 85.

[14] Whitehead, ‘The original drawings for the Historia naturalis Brasiliae of Piso and Marcgrave (1648)’, 409.

[15] On these and other pictorial sources see Whitehead, ‘The original drawings for the Historia naturalis Brasiliae of Piso and Marcgrave (1648)’, 409–22.

[16] I am grateful to Dr Jamie Maxwell, Natural History Museum, Ireland, for pointing out that while the Piso/Bondt bird has the casque and wattles of a cassowary, it is depicted with the bill and feet of an emu.

[17] Bondt, Jakob de, ‘Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex’, in Willem Piso, De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), pp 71–2.

[18] Brienen, ‘Georg Marcgraf (1610-c. 1644)’, 99–100.

[19] Pires-O’Brien, Maria Joaquina, ‘An essay on the history of natural history in Brazil, 1500-1900’, Archives of Natural History, 20, no. 1 (1993), 38.

[20] Whitehead, P. J. P., ‘The biography of Georg Marcgraf (1610-1643/4) by his brother Christian, translated by James Petiver’, Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History, 9, no. 3 (1979), 310. Christian Marcgrave’s ‘Vita Georgii Marggravii’ was published by him at Leiden in 1685 and subsequently included in J. J. Manget’s Bibiotheca scriptorium medicorum (Geneva, 1731), pp 262–64.

[21] Whitehead, ‘The biography of Georg Marcgraf (1610-1643/4)’, 309.

[22] Quoted in Brienen, ‘Georg Marcgraf (1610-c. 1644)’, 101.

[23] Smith, Paul J., ‘Marcgraf’s Fish in the Historia Naturalis Brasiliae and the Rhetorics of Autoptic Testimony’, in Françozo, Mariana (ed.), Toward an Intercultural Natural History of Brazil: The Historia Naturalis Brasiliae Reconsidered (New York, 2023), p. 123.

[24] Ibid., p. 124.

[25] Ibid., p. 125.

[26] Brienen, ‘Georg Marcgraf (1610-c. 1644)’, 97.

[27] Ibid., 95. Whitehead cites the latter’s biography on this point: ‘The Tribune of Soldiers, or ye Colonell of Mansfield hath told me what he himself by ye commands of yet Prince, had often conducted Marcgrave with 3000 soldiers in ye desarts, & caught many Birds & Fishes & brought ‘em to ye Prince’: ‘The biography of Georg Marcgraf by his brother Christian’, 309.

[28] Smith, ‘Marcgraf’s Fish in the Historia Naturalis Brasiliae’, p. 127.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Brienen, ‘Georg Marcgraf (1610-c. 1644)’, 96.

[31] Ibid., 85, 98.

[32] Smith, ‘Marcgraf’s Fish in the Historia Naturalis Brasiliae’, pp 136–7.

[33] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton, p. 150.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid., p. 151.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid., p. 152.