Parrots

‘There were no types of animals except for parrots’.[1]

In this quotation Fernando Colón (1488–1539), writing about his famous father Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), gives us some indication of the ubiquity of parrots in the New World. As Asúa and French note, they were the first birds of the Americas encountered by Columbus and they soon became emblematic of avian life in the New World.[2]

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1646), i, p. 667: ‘White-crested parrot’ (possibly a White Cockatoo (Cacatua alba)).

It is no surprise to find that the Italian natural historian Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), who took a keen interest in unusual and exotic birds, was fascinated by parrots, and wrote extensively about them. Aldrovandi was well-placed to observe such birds since, as he himself noted, parrots were the preserve of the wealthy and he had excellent connections to a number of sixteenth-century courts.[3] He often tells his readers how, where, and when, he had seen various parrots and who owned them. For example, this particular ‘White crested parrot’ was a bird which had once belonged to Cardinal Alessandro Farnese (1520–89).[4] Aldrovandi had clearly seen it alive for he noted that its eyes had yellow irises and black pupils, and that it was entirely covered with white feathers, including the white feathers in its crest.[5] From this we can deduce that he was talking about a white cockatoo (Cacatua alba).

Aldrovandi thought that parrots were somewhat like birds of prey but also differed from them in a number of ways.[6] As usual, he mined ancient sources for references and he concluded that the ancients such as Pliny the Elder (23/24–79), had thought parrots came from India alone, and that the majority from hence were green in colour.[7] However, early modern exploration had brought back a range of parrots from across the globe – and Aldrovandi highlighted the activities of Spanish explorers who had demonstrated that there was a wide variety of parrots waiting to be discovered.[8] From Gujarat and Kolkata in India, to Mexico, Aldrovandi introduced his readers to a plethora of parrots and tried to classify them on the grounds of size, origin, colour and call. He tells us that the parrots of Mexico were green, while in the Moluccas, Brazil and Ethiopia parrots were red, and in East India some were purple.[9] As Joannes Jonstonus (1603–75), said of parrots (paraphrasing Aldrovandi) in 1657: ‘No man could hitherto paint sufficiently all its colours’.[10]

Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, Cacatua galerita (Latham, 1790), NMINH:1903.247.1. © NMI

While Aldrovandi was interested in the wide variety of colours sported by parrots across the globe, he also paid close attention to their anatomy, especially their beak. He noted that their beak was said to be extremely hard and queried why this might be the case.[11] Aldrovandi was, as we have seen, interested in bird anatomy and included in his section on parrots the results of his dissections. He considered the beak of parrots to be unique.[12] Jonstonus explains why: ‘The Parrot alone with the Crocodile, moves his upper mandible; also his Beck, which is common to no other, where it is joyned to his neck, is open beneath under his chops’.[13]

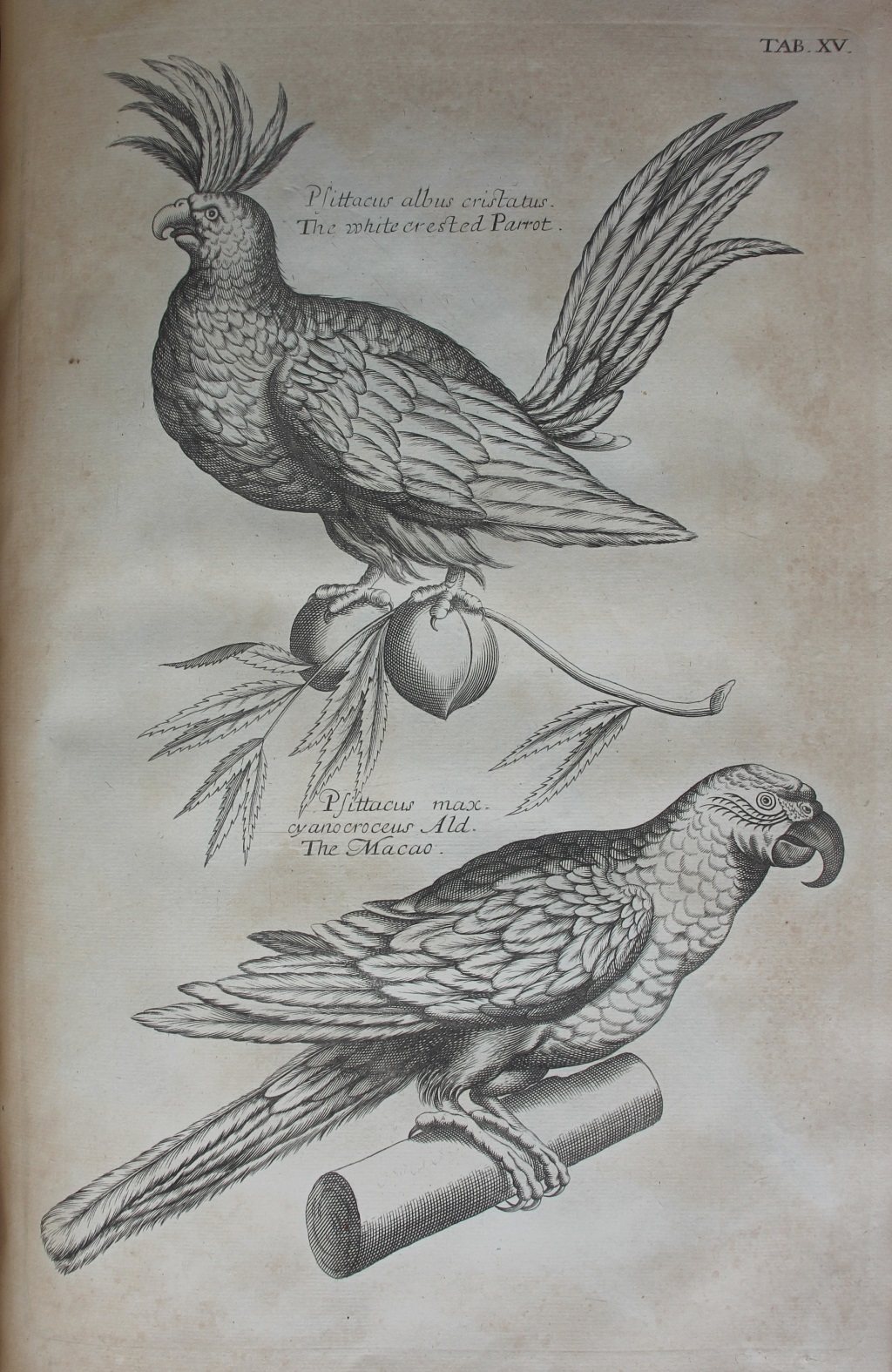

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XV: ‘The White-crested parrot and the Macau parrot’ – the latter is likely the blue-and-gold macaw (Ara ararauna).[14]

Alrovandi’s heavily illustrated and detailed treatise on parrots in his magnum opus was regarded as authoritative by other early modern ornithologists and it clearly formed the basis of later analysis of parrots by the Polish scholar Joannes Jonstonus and the English ornithologists Francis Willughby (1635–72), and John Ray (1627–1705). In this image Willughby and Ray simply re-used Aldrovandi’s woodcuts (albeit reversing them), and much of their text on parrots was a reworking of Aldrovandi. Willughby and Ray, with their normal clarity, divided parrots into three types, based on size: ‘The greatest are equal in bigness to our common Raven: or (as Aldrovandus saith) to a well-fed Capon; and have long Tails: In English they are called Macaos and Cockatoons. The middle or meansized and most common Parrots are as big or bigger than a Pigeon, have short Tails, and are called in English, Parrots and Poppinjayes. The least are of the bulk of a Blackbird or a Lark, have very long Tails, and are called in English Parakeetos’.[15] Edward Worth (1676–1733), had images of all these kinds of parrots in his wonderful ornithological collection.

Willughby began his second chapter on parrots by focusing on ‘Of the greatest sort of Parrots called Maccaws and Cockatoons’.[16] Brightly coloured macaws were especially prized and we know that they were among the first parrots brought back to Spain to delight their royal majesties, Isabella I of Castile (1451–1504), and her husband Ferdinand II of Aragon (1452–1516).[17] There was clearly a lucrative trade in parrots for Nicolás Monardes (1493–1588), whose treatise on medicines from the New World was included in Worth’s copy of Carolus Clusius’s Exoticorum libri decem: quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiæ describuntur: item Petri Bellonii observationes eodem Carolo Clusio interprete (Antwerp, 1605), mentions that parrots were among the many goods shipped annually into Seville.[18] Birkhead notes that a lively trade in parrots ensued and suggests that within a few decades, parrots were becoming ‘almost commonplace’.[19]

Aldrovandi had begun his section on individual parrots with a description of ‘the large blue and yellow one’ – clearly an Ara ararauna – and he reported that he had seen this bird in Mantua in 1572, at the palace of Guglielmo Gonzaga (1538–87), Duke of Mantua, and had been impressed by its size – indeed he considered the ‘Blue and Yellow Macau’ to be the largest of any parrot he encountered.[20] Duke Guglielmo had been given the bird as a gift (parrots were often presented as high-status gifts). Aldrovandi tells us that a similar bird ended up in a good home with ‘Franciscus Sforza, Count of S. Flora’, who loved the bird – indeed Aldrovandi draws a pen picture of an affecting deathbed scene for the bird, where the count and his son mourned its passing.[21] The count in question was Francesco Sforza , II Marquis of Castell’Arquato (1562–1624), who, as Aldrovandi notes, was subsequently made a cardinal by Aldrovandi’s illustrious relative Pope Gregory XIII (1502–85).[22]

The bird was, as Aldrovandi notes, ‘most beautiful’.[23] Willughby and Ray give a precise description of a ‘Blue and Yellow Maccaw’, based on that of Aldrovandi:

Aldrovandus his greatest blue and yellow Maccaw. The body of this equals a well-fed Capons. From the tip of the Bill to the end of the Tail it was two Cubits long. The Bill hooked, and in that measure that it made an exact semicircle, being outwardly conformed into the perfect roundness of half a ring, a full Palm long; and where it begins as thick within half an inch, if you measure both Mandibles. The upper Mandible is almost two inches longer than the nether, which on the lower side downward is convex and round. The whole Bill is black. The Eyes white and black. Three black lines drawn from the Bill to the beginning of the Neck, representing the figure of the letter S lying, compass the eyes underneath. The Crown of the Head is flat, and of a green colour. The Throat adorned with a kind of black ring. The Breast, Belly, Thighs, Rump, and Tail underneath all of a Saffron colour. The Neck above, Back, Wings, and upper side of the Tail of a very pleasant blue or azure. The Tail eighteen inches long more or less. The Legs very short, thick, and of a dusky or dark colour, as are also the Feet, the Toes long, armed with great, crooked black Talons.[24]

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 298: a small green parrot.

Aldrovandi had noted French ornithologists called parrots ‘Parroquets’, small parrots which he considered to be the most intelligent of all parrots for not only could they imitate human speech, some were said to be able to speak words clearly.[25] Indeed, Jonstonus memorably stated that ‘One was taught that would say the Creed to a Cardinal’![26] Pierre Belon (1517–64), the foremost French ornithologist, had far less to say about parrots and parakeets than Aldrovandi, but he did include them in his history of birds. Belon, with his emphasis on exploring what ancient authorities such as Aristotle (384–322 BC), or Pliny the Elder, had said about parrots, concentrated on the green parrots known to them in much of his text, but he also acknowledged that the exploration of Brazil had uncovered parrots and (smaller) parakeets of a range of hues.[27]

Dominique Crowley: Monstrorum, RHA Ashford Gallery

Dominique Crowley, Arcadian Sunset, Diptych, 2024, oil, acrylic ink and acrylic resin on wood panel, 100cm x 200cm. Bird: Rose-ringed Parakeet. © Dominique Crowley 2024, image courtesy of the artist.

Belon linked parakeets and the colour green and in this beautiful painting by Dominique Crowley, you can see why. He noted that some wished to distinguish between larger parrots and smaller, predominantly green, parakeets but he did not give his own views. The Rose-ringed Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) in this painting, is not associated with Brazil but has ranges in Africa and India.

Willem Piso’s commentary on Jakob de Bondt’s ‘Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex’ in Willem Piso, De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), p. 63: ‘A small parrot’.

Jakob de Bondt (1592–1631) provides much more information about parakeets in his Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex. However, he makes it clear that the parrots and parakeets he discussed had been encountered by him on his travels in the Mediterranean. He considered these small birds (which he estimated to be the size of a lark), to be especially beautiful birds.[28] He described one parakeet as having a reddish head, neck and (upper) tail. Its breast and lower tail were pink shading into greens and blues. It had predominantly green wings, with some red feathers interspersed and some yellow and pink, appearing almost golden in the sun. No wonder that they were, as he noted, prized by noblemen![29]

Ring-Necked Parakeet; Drumcondra, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Asúa, Miguel de, and Roger French, A New World of Animals: Early Modern Europeans on the Creatures of Iberian America (Aldershot, 2005).

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Birkhead, Tim, Birds and Us: A 12,000–Year History, from Cave Art to Conservation (London, 2022).

Colón, Fernando, Historia del Almirante, edited by Luis Arranz (Madrid, 1984).

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

Willem Piso’s commentary on Jakob de Bondt’s ‘Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex’ in Willem Piso, De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658).

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Colón, Fernando, Historia del Almirante, edited by Luis Arranz (Madrid, 1984), p. 112.

[2] Asúa, Miguel de, and Roger French, A New World of Animals: Early Modern Europeans on the Creatures of Iberian America (Aldershot, 2005), pp 1–2.

[3] Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1646), i, p. 634.

[4] Ibid., p. 668.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., p. 634.

[7] Ibid., p. 635.

[8] Ibid., p. 636.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657), p. 186. This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

[11] Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I], p. 637.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Jonstonus, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes, p. 187.

[14] I am grateful to Dr Paolo Viscardi for this suggested identification.

[15] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 110. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[16] Ibid., p. 110.

[17] Asúa and French, A New World of Animals, p. 2.

[18] Ibid., p. 106.

[19] Birkhead, Tim, Birds and Us: A 12,000–Year History, from Cave Art to Conservation (London, 2022), p. 144.

[20] Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I], p. 663.

[21] Ibid., p. 664.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 110.

[25] Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I], p. 636.

[26] Jonstonus, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes, p. 187.

[27] Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), pp 296–7.

[28] Willem Piso’s commentary on Jakob de Bondt’s ‘Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex’ in Willem Piso, De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), p. 63.

[29] Ibid.