Perching Birds

Perching birds (also known as passerines and songbirds), make up more than half of all bird species in the world.[1] They account for around 6,500 species, divided into 140 families.[2] It is therefore no surprise to see them so well represented in Worth’s books.

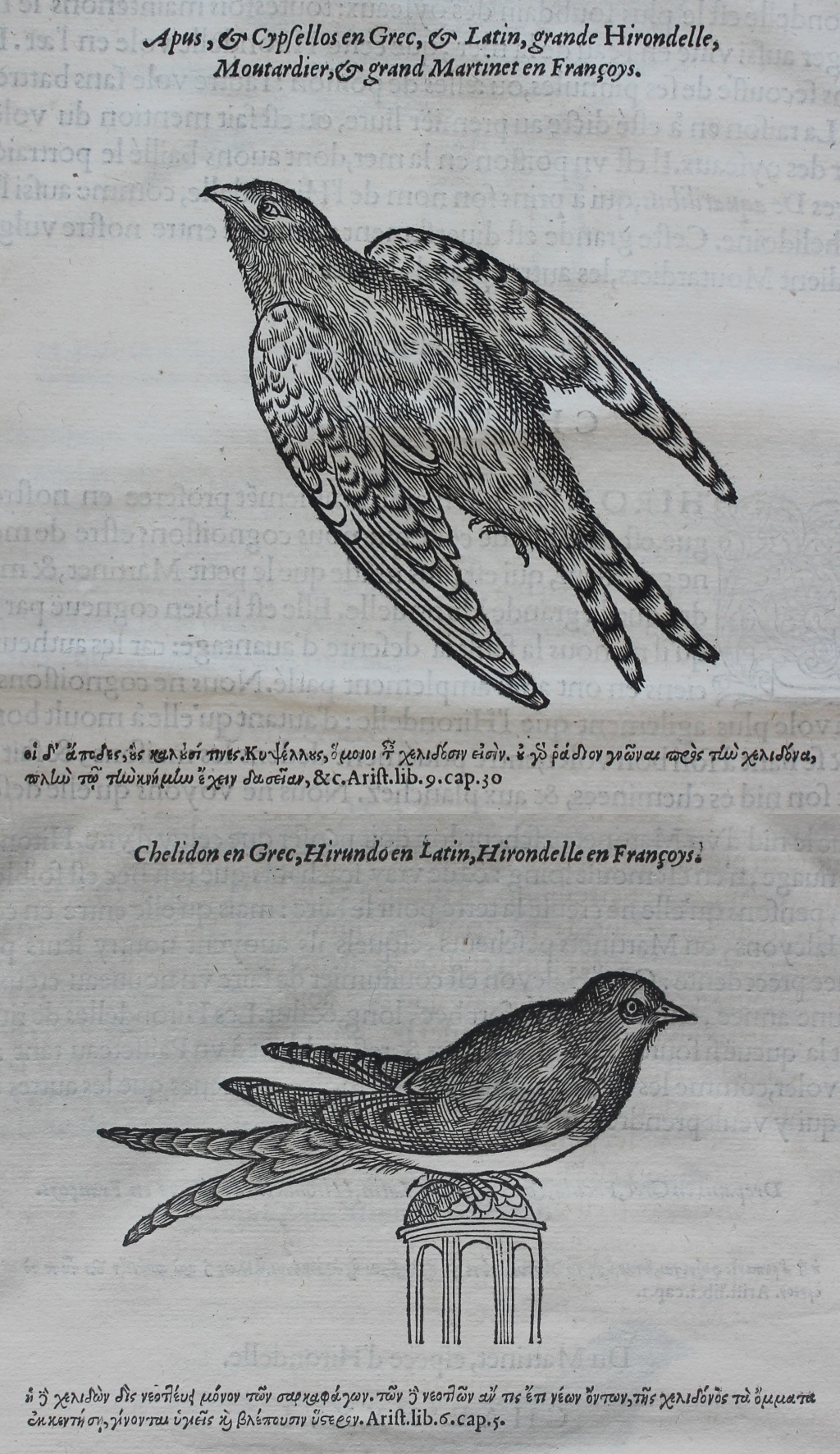

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 377: On top: Swift; bottom: Swallow.

Images of passerines can be seen perching on branches throughout Worth’s copy of Pierre Belon’s beautifully illustrated L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), but sometimes it could be difficult to tell a passerine and a non-passerine apart. These images from the latter section of Belon’s book, of a swift (top) and swallow (below), are an example of this. Swifts, swallows and martins were among the final birds to be discussed by Belon (1517–64), in his seventh (and last) section of L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux. He began by discussing what he called the ‘grand hirondelle’ and mentioned four kinds commonly known in France beginning with a description of the largest one, named ‘Apus et Cypsellos’, which he stated had a different stance than other swallows.[3] Belon noted that his bird had good eyesight and a large mouth, crucial characteristics which allowed it to catch prey in flight.[4] He reckoned that his ‘large swallow’ was about as big as a starling, and described it as having a small black pointed beak, feathers which were more mouse-coloured than truly black, and a white patch on its throat.[5] This description suggests that Belon’s large ‘swallow’ was a swift, for swifts, not swallows, have this distinguishing mark on their throat. In addition Belon drew attention to the ability of his ‘big swallow’ to glide, moving swiftly through the air without flapping their wings and he noted that they were the last to arrive and the first to leave.[6] This final piece of information confirms that his large ‘swallow’ was actually a swift because Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica), tend to arrive in Britain and Ireland between the months of April and October, whereas Common Swifts (Apus apus), are Summer visitors between May and August.[7] Belon, like Aristotle (384-322 BC), before him (and many of us since), was mixing his swallows and his swifts! Its forked tail, which he describes as forming an arc with its wings in flight is clearly apparent in his accompanying image – seen in the top part of this combined image.[8]

Belon’s description of his ‘petite Hirondelle’ is much closer to a swallow. Size-wise he declared that it was larger than a Martin and smaller than his ‘large swallow’.[9] Rather tantalizingly he decided that because it had been described by ancient authorities and was so well known, there was no need to describe it![10] But he does give us enough information about his ‘petite Hirondelle’ to be sure that this time we are dealing with a swallow for not only does he note their liking for making nests in buildings and chimneys but crucially he also draws attention to their colouring: feathers dark brown learning towards black but underneath a white belly, black stomach and red feathers underneath the beak.[11] This corresponds closely to the description of a Barn Swallow in Collins Bird Guide: ‘Blue-glossed black above, white or buffish-white below (in most of Europe), with blue-black breast-band and blood-red throat and forehead’.[12]

On top left Swallow; Donabate, Dublin; on top right Crossbill; Sally Gap, Wicklow; on bottom House Sparrow; Phibsborough, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly

In this image we can see exactly what Belon meant about his Barn Swallow: the bird at the top left of the image is a swallow and it is joined by two other passerine birds: a Crossbill and a House Sparrow. Belon, Aristotle et al. might confuse swallows and swifts but swifts, unlike swallows, crossbills and sparrows, were non passerine birds. As Svensson et al. note, swifts ‘spend most of their lives flying; when migrating and in winter, they sleep most nights at high altitude in the air’.[13] They do not, like passerines, typically have three toes pointing forward and one back (which allows passerines to easily perch on branches).[14] Belon was clearly aware of the perching nature of many songbirds since he frequently depicted them perching on branches. He certainly does in his image of sparrows, a bird he was well used to since he describes it as ‘a small bird, known throughout the world’.[15] His ‘big swallow’, on the other hand, is, as we have seen, depicted as being in flight.

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XLIIII: assortment of birds, including finches, a sparrow, and a red cardinal.

This image brings together a group of birds which the English ornithologist Francis Willughby (1635–72), called ‘Small birds with thick and short bills’. Among this group in his catalogue he included ‘The GROSBEAK, or Hawfinch, Coccothraustes: it is but seldom seen in England, and that only or chiefly in Winter. The GREEN-FINCH, called in the Northern parts of England the Green Linnet, Chloris. The BULL-FINCH, Alp, or Nope, Rubicilla seu Pyrrhula. The SHELL-APPLE, or Cross-bill, Loxia. This comes over sometimes in the Autumn, but seldom abides the whole year with us. The HOUSE-SPARROW, Passer Domesticus. The CHAFFE-FINCH, Fringilla. The BRAMBLE, or Brambling, Montisringilla … The GOLDFINCH, Carduelis, Acanthis’.[16] Many of these birds are grouped together in this image, with the odd one out being Willughby’s Virginian Nightingale, i.e. the Northern Cardinal, Cardinalis cardinalis (Linnaeus, 1758), which is explored among Worth’s images of exotic birds.

Willughby described a male House Sparrow as follows:

The Bill is thick, in the Cock black, at the corners of the Mouth between the Eyes yellowish, in the Hen dusky, scarce half an inch long: The Eyes hazel-coloured: The Legs and Feet of a dusky flesh-colour: The Claws black. The lower joynt of the outmost Toe, as in other small birds, grows to that of the middle Toe. The Head is of a dusky blue, or ash-colour; the Chin black. Above the Eyes are two small white spots. From the Eyes a broad line of a spadiceous colour. The feathers growing about the Ears are ash-coloured. The Throat [below the black spot] of a white ash-colour. Under the Ears on each side is a great white spot. The lower Breast and Belly are white. The feathers dividing between the Back and Neck, on the outside the shaft are red, on the inside black, but toward their bottoms something of white terminates the red. The rest of the Back and Rump are of the same colour with Thrushes. made up as it were of a mixture of green, dusky, and ash-colour.[17]

His description owed much to Aldrovandi but he did not agree that the House Sparrow was necessarily a ‘short-lived bird’.[18] His depiction of a crossbill (beside the sparrow) makes it clear where that bird got its name!

Top left: Hawfinch, Coccothraustes coccothraustes (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1885.91.1. © NMI; top right: Red Cardinal, Cardinalis cardinalis (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1890.63.1. © NMI; bottom right: Bullfinch, Pyrrhula pyrrhula (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1932.6.11. © NMI; bottom left: Greenfinch, Loxia chloris Linnaeus, 1758, NMINH:1882.647.1. © NMI

Willughby, though not the first to describe finches, provided his readers with detailed descriptions of a number of different types, and like Belon, he began with a Bullfinch, a bird which he had evidently examined in detail:

This Bird hath a black, short, strong Bill, in figure and structure like that of the Grosbeak, but less. [In the elder birds it is something crooked.] The Tongue is as it were cut off: Its Eyes are hazel-coloured: Its Claws black: Its Legs dusky. The lower joynt of the outmost Toe sticks fast to the middle Toe. The Head for the proportion of the body is great. In the Male a lovely scarlet or crimson colour illustrates the Breast, Throat, and Jaws, as far as the Eyes. The feathers on the crown of the Head above the Eyes, and those that compass the Bill, are black: The Rump and Belly white: The Neck and Back grey, with a certain tincture of red. [The Neck, Back, and Shoulders seemed to me blue or ash-coloured.] The quil-feathers of the Wings are in number eighteen; the last or inmost of which on the outer half from the shaft is red, on the inner black and glossie. Of the rest the interiour [i.e. those next the body] are black, with a gloss of blue; the exteriour dusky or black. Of the first or outmost five the exteriour edges in the upper half of the feathers are somewhat white. The tips of the lower covert-feathers are cinereous, in the interiour more, in the exteriour less. The next to these are of the same colour with the Back. The Tail is two inches long, black, and shining, made up of twelve feathers. The Cock is of equal bigness to the Hen, but hath a flatter crown, and excels her in the beauty of his colours.[19]

He was also clearly interested in the habitat of finches and tells us that bullfinches fed on the leaves and flowers of fruit trees, such as apple, pear and peach trees. Unfortunately because of this they were not well-liked by gardeners![20] He also gives us information about their song, quoting both the English naturalist William Turner (1509/10–68), and the Italian natural historian Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605):

Turner writes, that they are very docile birds, and will nearly imitate the sound of a Pipe [or the Whistle of a man] with their voice. They are much esteemed for their singing with us in England, and deservedly in my judgment. For therein they excel all small birds, if perchance you except the Linnet. I hear (saith Aldrovandus) that the Hen in this kind sings as well as the Cock, contrary to what is usual in most other sorts of birds.[21]

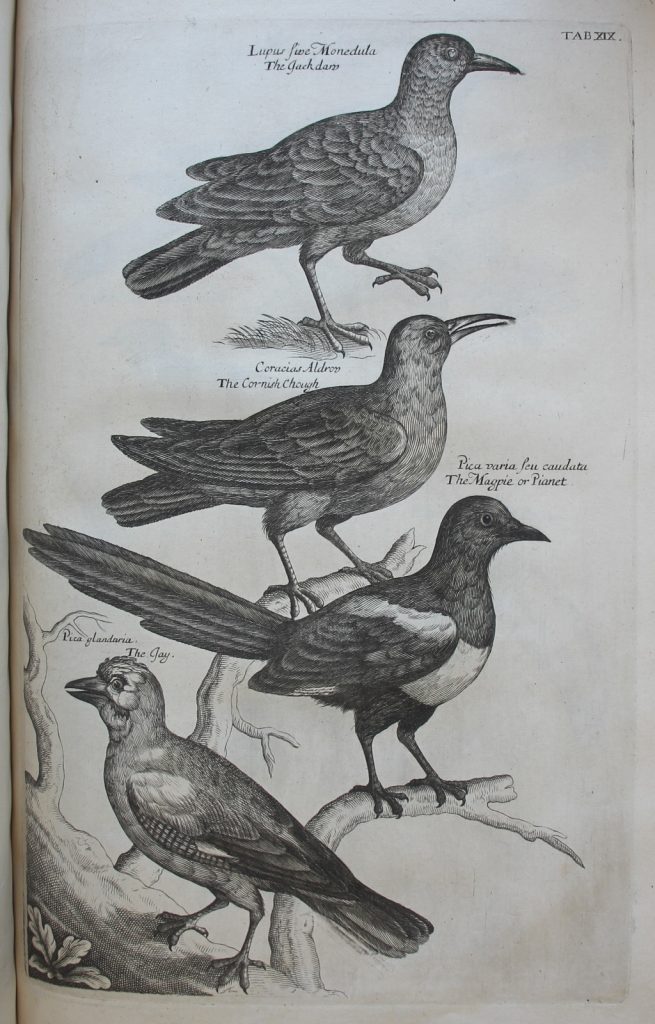

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XIX: Jackdaw, chough, magpie and jay.

Willughby (and Ray), had a lot to say about jackdaws, choughs, magpies and jays, birds which, along with ravens, crows and rooks, they called ‘The Crow Kind’ and ‘The Pie-Kind’, which formed a subset of ‘Birds with thick, streight, and large Bills’.[22] Magpies have long had a ‘bad press’ and the superstitious rhyme ‘One for sorrow, two for joy’ has not helped their image. As Strycker notes, in Scotland magpies were associated with death, while in France and Sweden magpies were considered to be thieves.[23] But they are in fact rather beautiful birds – a fact noted by Willughby and Ray:

The Head, Neck, Throat, Back, Rump, and lower Belly are of a black colour; the lower part of the Back near the Rump is more dilute, and inclining to cinereous. The Breast and sides are white, as also the first joynt of the Wing. The Wings are smaller than the bigness of the body would seem to require. The Tail and prime feathers of the Wings glister with very beautiful colours (but obscure) of green, purple and blue mingled, only in the exteriour Vanes. The number of beam feathers is twenty; of which the outmost is shorter by half than the second; the second also shorter than the third, and that than the fourth, but not by an equal defect; the fourth and fifth are the longest of all. The eleven foremost about their middle part, on the inside of the shaft are white, the white part from the extreme feather gradually decreasing, till in the tenth it be contracted into a great spot only.[24]

These were the normal colours of a Magpie, but there could be variations for Willughby and Ray had spotted ‘brown or reddish ones’ in the royal aviary at St James’s Park.[25] Willughby and Ray seem to have been drawn to magpies (and rightly so), because they also commented favourably on a less well-known ability of the bird:

This Bird is easily taught to speak, and that very plainly. We our selves have known many, which had learned to imitate mans voice, and speak articulately with that exactness, that they would pronounce whole Sentences together so like to humane Speech, that had you not seen the Birds you would have sworn it had been man that spoke.[26]

As Strycker reminds us, magpies are among the most intelligent of all animals.[27]

Top left: Jackdaw; Phoenix Park, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly; top right: Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1883.23.1. © NMI; bottom right: Magpie; Bull Island, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly; bottom left: Jay; Glasnevin, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly

Willughby and Ray might call a Chough ‘Cornish’ but they made it clear that it could be found in Wales and England also, usually in the vicinity of rocks, old castles and churches by the sea.[28] Their Cornish Chough was ‘like a Jackdaw, but bigger, and almost equal to a Crow’ and they clearly had dissected one:

It differs chiefly from the Jackdaw in the Bill, which is longer, red, sharp, a little bowed or crooked: The upper Mandible being something longer than the lower. The Nosthrils round: The Tongue broad, thin, and a little cloven, shorter than the Bill. The sides of the fissures of the Palate and Windpipe and of the root of the Tongue are rough, and as it were hairy. Feathers reflected downwards cover the Nosthrils. The Feet and Legs are like those of a Jackdaw, but red of colour. The Plumage of the whole body all over is black.[29]

Dominique Crowley: Monstrorum, RHA Ashford Gallery

Dominique Crowley, Two birds, Vignette, 2024, oil and acrylic resin on wood panel, 40cm x 40cm. Bird: Irish Jay. © Dominique Crowley 2024, image courtesy of the artist.

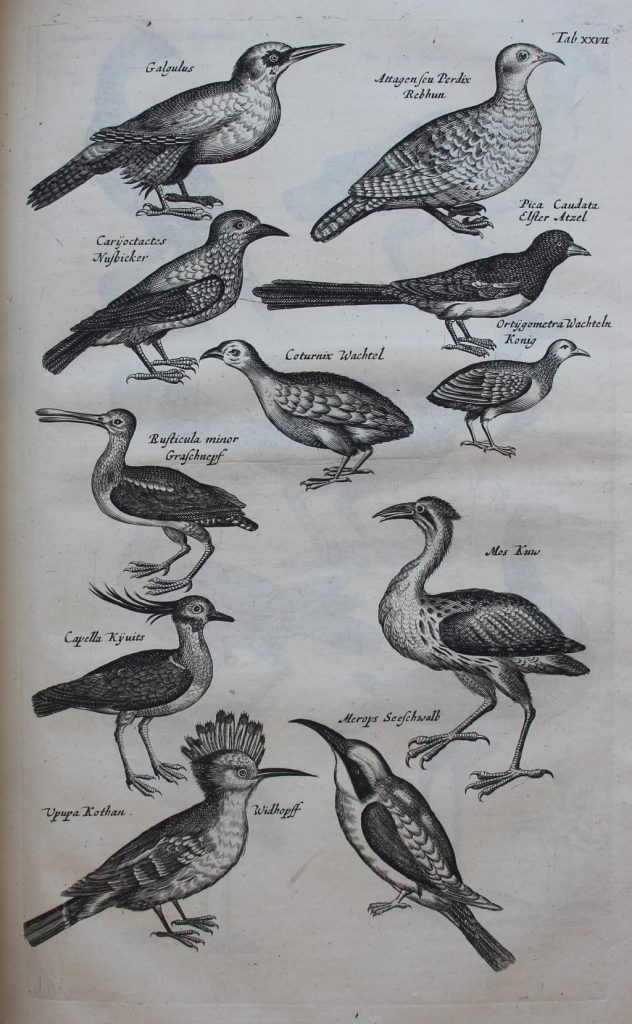

Magpies were not the only ones who could imitate human voices: according to Willughby some of the ‘Crow Kind’ had similar abilities. Jays, we are told, could ‘imitate mans voice, and speak articulately as well as a Jackdaw’.[30] Willughby called Jays ‘Pica glandaria’, from their penchant for acorns, but noted that they could be equally greedy when presented with a cherry![31] According to Joannes Jonstonus (1603–75), chestnuts were considered an acceptable food source for Magpies and he too was impressed by their vocal abilities, repeating Plutarch’s claim that Roman magpies, having heard the sound of a trumpet, perfectly repeated it, and commenting that ‘The Pie almost every hour changeth her note; she learnes and loves to speak as men do.[32] In the plate below, from Jonstonus’s Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657) we see his ‘Pica Caudata’, which, with its very long tail, is clearly an Eurasian Magpie (Pica pica). It and the Nutcracker, Nucifraga caryocatactes, in the plate are heavily outnumbered by non-passerine birds such as waders like the Lapwing, Vanellus Vanellus, and Snipe, Gallinago gallinao, and other non-passerine birds such as the Bee-eater, Merops apiaster – not to mention the Hoopoe in the bottom left corner of the plate!

Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), plate XXVII includes a magpie but also non-passerine birds.

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Avibase – The World Bird Database.

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

Moss, Stephen, Ten birds that changed the world (London, 2023).

Strycker, Noah, The Magic and Mystery of Birds: The surprising lives of birds and what they reveal about being human (London, 2014).

Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022).

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Moss, Stephen, Ten birds that changed the world (London, 2023), p. 171.

[2] Ibid., p. 20.

[3] Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 376.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., pp 376–7.

[6] Ibid., p. 378.

[7] Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022), pp 270 and 244.

[8] Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, p. 377.

[9] Ibid., p. 378.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Svensson, et al., Collins Bird Guide, p. 270.

[13] Ibid., p. 244.

[14] Swifts have four toes, usually facing forward though they do have the ability to rotate two toes.

[15] Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, p. 361.

[16] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 25. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[17] Ibid., p. 249.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., p. 247.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid., pp 22, 121.

[23] Strycker, Noah, The Magic and Mystery of Birds: The surprising lives of birds and what they reveal about being human (London, 2014), p. 191.

[24] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 127.

[25] Ibid., p. 128.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Strycker, The Magic and Mystery of Birds, p. 192.

[28] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 126.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid., p. 130.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657), p. 188. This English translation is not in the Worth Library.