Pigeons and Doves

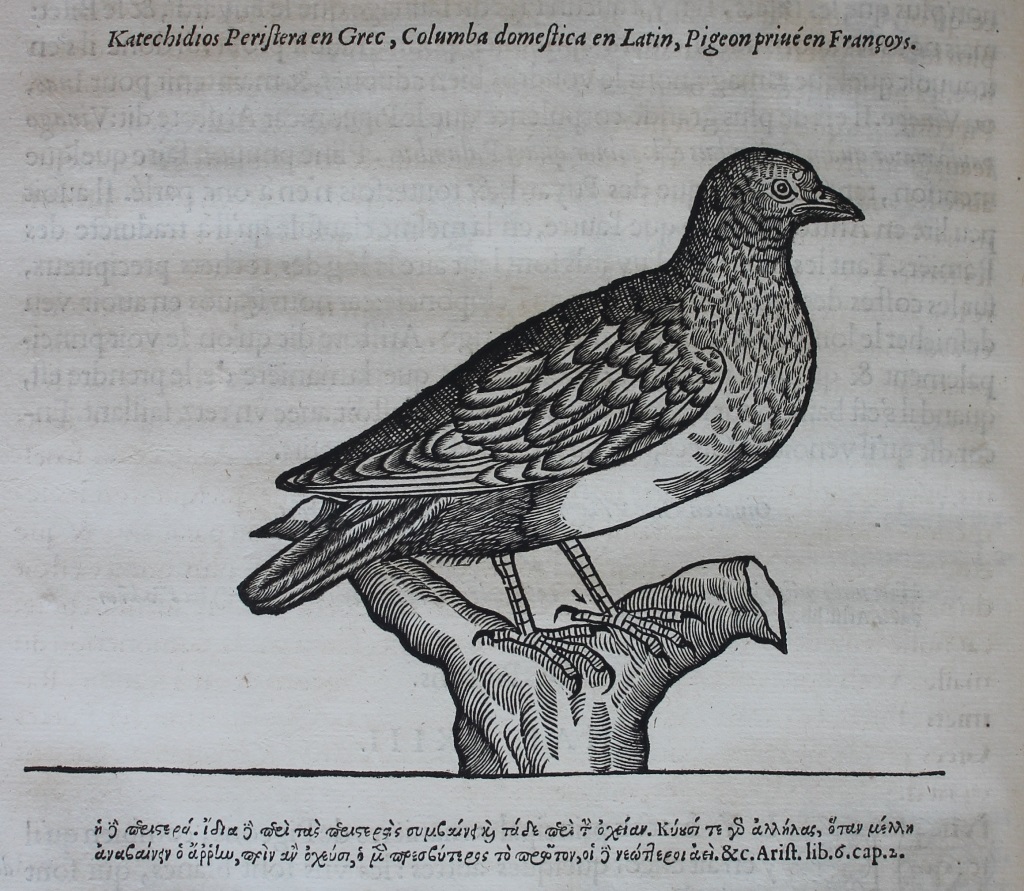

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 314: ‘Columba domestica’. Pigeon.

When commenting on pigeons and doves, Pierre Belon (1517–64), and other sixteenth-century ornithologists such as Conrad Gessner (1516–65), and Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), usually concentrated on what ancient authorities such as Aristotle (384–322 BC), and Pliny the Elder (23/4–79), had noted about the birds. Aristotle’s definition was particularly influential:

Of the pigeon family there are many diversities; for the peristera or common pigeon is not identical with the peleias or rock pigeon. In other words, the rock-pigeon is smaller than the common pigeon, and is less easily domesticated; it is also black, and small, red-footed and rough-footed; and in consequence of these peculiarities it is neglected by the pigeon-fancier. The largest of all the pigeon species is the phatta or ring-dove; and the next in size is the oenas or stock-dove; and the stock-dove is a little larger than the common pigeon.[1]

Belon divided pigeons into three different types: ‘domestic pigeons’, some of which were white; ‘wild pigeons’ with black spots on their wings; and a third group which he calls ‘mixed’, though he noted the wide variety of pigeons visible in his own time.[2] He noted that in Rome racing pigeons were a highly prized commodity, and like Pliny the Elder he was impressed by the ability of pigeons to deliver letters.[3] Indeed, Belon alludes to Pliny the Elder’s anecdote on the role played by pigeons at the siege of Mutina (now Modena), when Mark Anthony (83–30 BC), was besieging Decimus Brutus (81–43 BC), in 43 BC. Mark Anthony thought he had Brutus cut-off from Octavian’s forces but Brutus used pigeons to communicate with Caesar’s nephew. As Pliny the Elder (and Belon) observed: ‘what use to Antony were his rampart and watchful besieging force, and even the barriers of nets that he stretched in the river, when the message went by air?’[4] Pigeons, especially the racing of Triganini pigeons, continue to be popular in Modena to this day.[5]

Pigeons have been domesticated for thousands of years – as Pizzuti Piccoli notes, the ancient Egyptians used them for rituals four thousand years ago.[6] This was certainly not great news for pigeons – Moss relates that Pharoah Rameses III sacrificed 57,000 pigeons to the god Amun Ra at Thebes and they are mentioned in the Bible as a staple offering at temples.[7] Despite this carnage the geographical spread of the domestic pigeon is very wide indeed and there is a plethora of breeds – around 1050 were noted in Europe alone in 2020, primarily due to the popularity of pigeon breeding and racing, a sport which is ancient but which has been increasingly popular since at least the seventeenth century.[8] In Ireland, pigeon racing is governed by the Irish Homing Union and, as Amelie Bias Woodlock notes, ‘Pigeon racing is a sport and a passion that has a long and deep-rooted history in Ireland and Britain’.[9]

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637), ii, p. 499: Stock dove.

Stock Dove; Donabate, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Aldrovandi’s ‘Oenas mas cum vicia’ (Stock Dove), probably sighted near Bologna, is, as Donegan notes, the lectotype of S. oenas.[10] Aldrovandi provided his readers with images of both a male and female stock dove and he was, as Pizzuti Piccoli reminds us, the first to write a scientific treatise on the various breeds of pigeons of his time.[11] The stock dove population in Ireland is facing challenges: according to the National Biodiversity Data Centre, stock doves breeding populations have been declining and it is now ‘Red-listed’ according to Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026.[12] BirdWatch Ireland explains that this decline in the breeding populations of stock doves in Ireland is due to habitat loss and the use of synthetic pesticides, which kill the wild-flowers which stock doves forage.[13]

Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), plate 32: Pigeons and Doves.

Aldrovandi’s illustrations of pigeons and doves certainly proved influential – we see some of them reproduced by Joannes Jonstonus (1603–75), in plate 32 of his Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657). In the above plate we can see his ‘Columba Livia’ in the bottom right corner: this rather basic image is based on one of Aldrovandi’s illustrations. It lacks clarity and so too do some of Jonstonus’s identifications: as Donegan notes he provides two images of ‘Turtur’ (turtle dove) – one, beneath his ‘Columba Livia’, does indeed resemble a turtle dove but the ‘Turtur’ above the ‘Columba Livia’, with its striking white head, is perhaps a feral pigeon instead.[14]

Jonstonus’s general comments on pigeons also leave much to be desired and are a good example of his ‘mapgie-like’ approach to information:

The Pigeon when she layes two eggs, the one egg will bring a male, the other a female; but because the heat is greater in the male, he is said to be first hatcht, Paul. à Castro. When the young ones are brought forth, she thrusts the salt Earth into their mouthes, which she hath first fitted in her own, to prepare them to receive some meat, and to implant fruitfulnesse into them, and to raise their appetite, Athen. 9. hist. c. 24. Many things prove them to be apt to learn. One of them pecked corn out of Mahomet’s ear. When Leyden was besieged, some of them carried Letters, Lipsius. The same was done at the siege of the Buss. Divers men use divers remedies to keep them in the Dove-houses, and to allure others thither. Some stir Man’s blood up and down in an earthen vessell for a quarter of an hour, with Pease, and then anoint Pigeons with it, and cast the pease to them to eat, Gesner. Some hang the skull of an old man in the Dove-house, Albertus. Some hang a piece of the halter that a man was hang’d with, on their windows, Pallad. l. 3. c. 44. Pliny (l. 11. c. 37,) writes, That there is poyson in mans teeth that will kill young unfeather’d Pigeons. We have it from the secrets of the Egyptians, that such as feed on Pigeons flesh will never be infected with the Plague. Hence in times of pestilence onely Princes feed on them. Cardanus prescribes them with their broth. Their dung is so hot, that being fired by the Sun, it hath fired houses, saith Galen. The same Author useth it for a hearing remedy; and being bruised dry with the seed of Cresses, some apply instead of Mustard for a rubisicative. Anno 1550. there was one taken in Germany with 4. feet, and 2. bellies; It was brought to the Emperour, and Electors; who all wonder’d at it.[15]

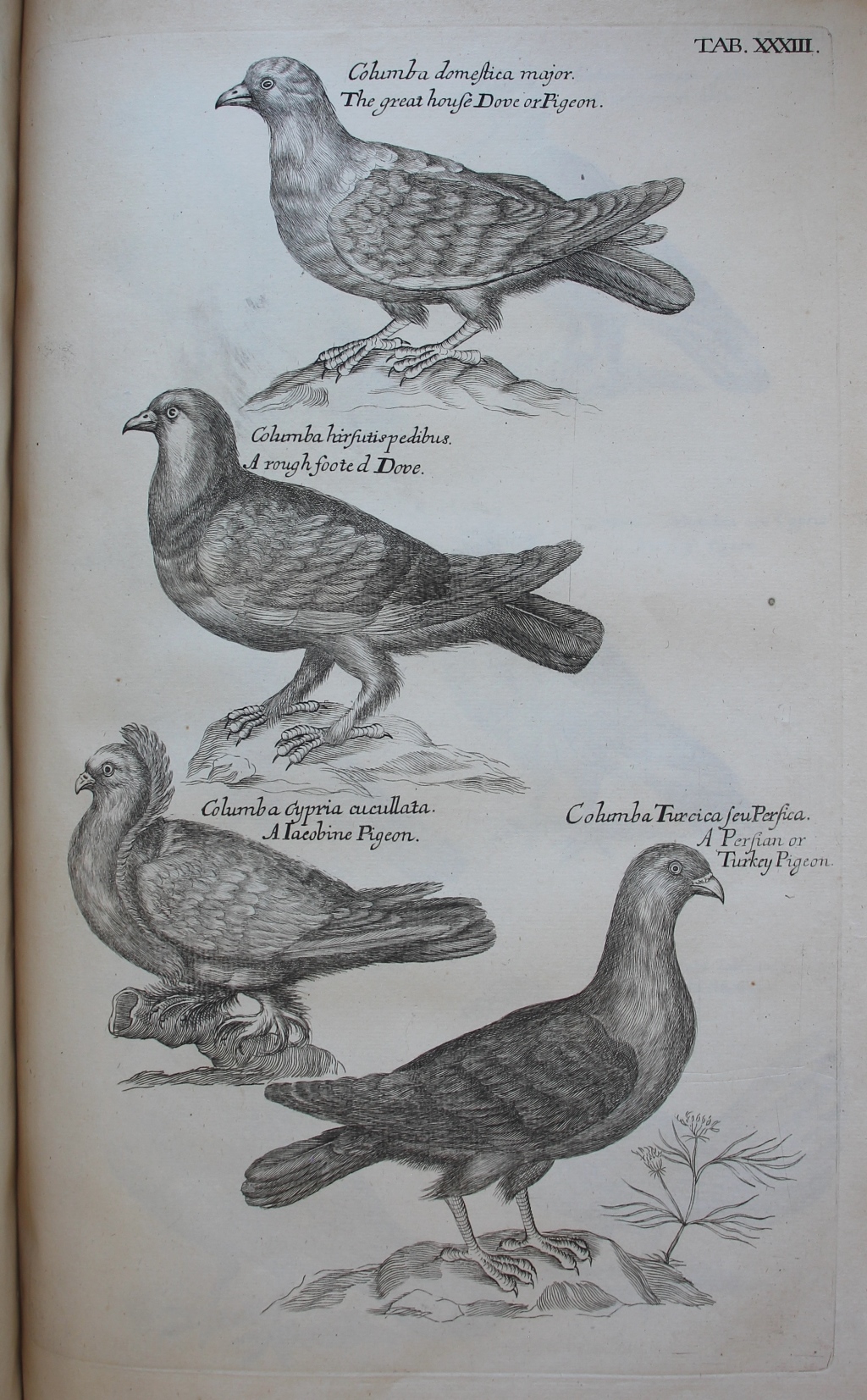

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XXXIII.

Francis Willughby (1635–72), and John Ray (1627–1705), provided considerably more scientific information about doves and pigeons for their readers. Willughby’s introductory section on domestic and feral pigeons is entitled ‘Columba domestica seu vulgaris’, which two years later Ray translated into English as ‘The common wild Dove or Pigeon. Columba vulgaris’.[16] He introduces his discussion with a detailed description of a female:

A Female, which we described, weighed thirteen ounces: Was in length from Bill to Tail thirteen inches; in breadth twenty six. Its Bill was slender, sharp-pointed, and indifferently long, like to that of a Lapwing or Plover, above the Nosthrils soft, and white by the aspersion of a kind of furfuraceous substance, else dusky. The Tongue neither hard, nor cloven, but sharp and soft. The Irides of the Eyes of a yellowish red. The Legs on the forepart feathered almost to the Toes: The Feet and Toes red; the Talons black. The Head was of a pale blue; the Neck as it was diversly objected to the light did exhibite to the Beholder various and shining colours. The Crop was reddish, the rest of the Breast and Belly ash-coloured. The Back beneath, a little above the Rump, was white, (which is a note common to most wild Pigeons) about the shoulders cinereous, else black, yet with some mixture of cinereous. The number of prime feathers in each Wing was about twenty three or twenty four. Of these the outmost were dusky, of the rest as much as was exposed to sight black, what was covered with the incumbent feathers cinereous. The covert-feathers of the ten first Remiges were of a dark cinereous: Of the rest of the covert-feathers (almost to the body) the tips and interiour Webs, as far as the shafts were cinereous, the exteriour black. The covert-feathers of the underside of the Wings purely white. The Tail is made up of twelve feathers, four inches and an half long, the middle being somewhat longer than the extremes. The tips of all were black: The two outmost below the black on the outside the shaft were white; all the rest wholly cinereous, the lower part being the darker. The feathers incumbent on the Tail were cinereous. It had a great Craw, full of Gromil seed. The blind Guts were very short, scarce exceeding a quarter of an inch. It hath (as we said of Pigeons in general) no Gallbladder, and lays but two Eggs at a time.[17]

Ray, commenting in 1678 on his English translation of Willughby’s Ornithologia of 1676, makes the point that ‘Under the title of Domestic, which I have Englished tame or house Doves, he comprehends the common wild Pigeon kept in Dove-cotes, which is of a middle nature between tame and wild’.[18] Dovecotes had been popular for centuries, allowing people to house doves and pigeons. During the medieval period dovecotes were the preserve of manorial lords but after 1500 more people began to build them (especially following the prerogative judgment of 1619 which ended the old manorial privilege), though they fell out of fashion in the eighteenth century.[19] Unfortunately, as McCann notes, dovecotes were not built for altruistic purposes – doves and pigeons were a source of food.[20] Indeed Morgan argues that ‘Food was at the root of human-pigeon relationships in early modern England’.[21] Not all agreed with their culinary use – Robert Burton (1577–1640), whose famous Anatomy of Melancholy Worth owned in a London 1676 edition – decried the eating of pigeons, declaring that they were ‘unwholsome dangerous melancholy meat’.[22]

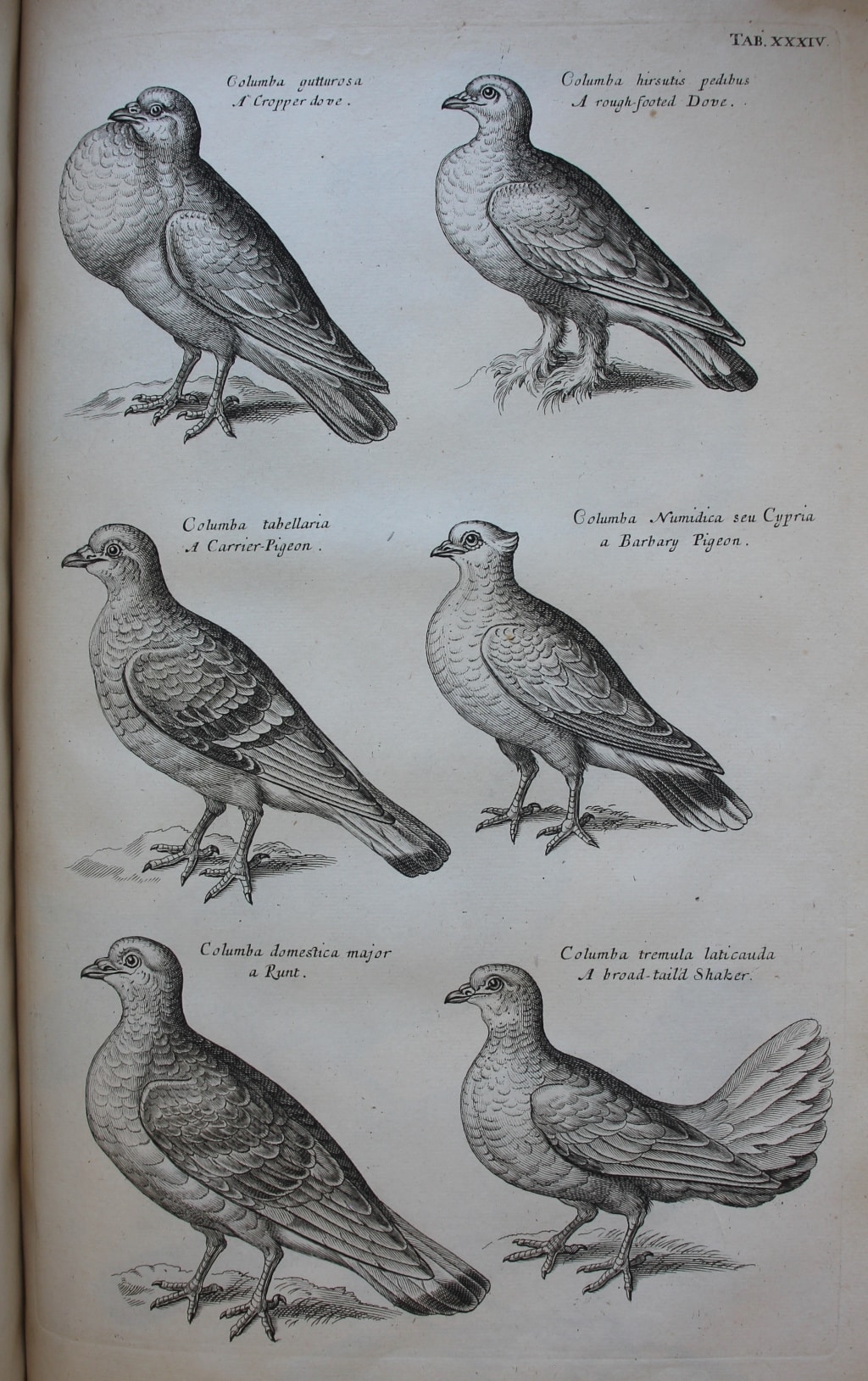

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XXXIV.

In this plate Willughby depicts ‘Columba gutturosa. A Cropper dove’; ‘Columba hirsutus pedibus. A rough-footed Dove’; ‘Columba tabellaria. A Carrier-Pigeon’; ‘Columba numidica seu Cypria a Barbary Pigeon’; ‘Columba domestica major a Runt’; and ‘Columba tremula laticauda A broad-tailed Shaker’. As we have seen, Willughby had already included a ‘Columba domestica major’ in plate XXXIII, which he had called ‘The great house Dover or Pigeon’, and Donegan argues that the earlier plate XXXIII image correlates to his description of what he calls Columba domestica sue vulgaris, a domestic or feral pigeon.[23] The image was clearly based on Aldrovandi’s ‘Columba domestica varij coloris cum piso’. The wings of Aldrovandi’s bird appear rather high – possibly, as Donergan suggests, because the Aldrovandi’s image was based on a stuffed bird.[24]

Willughby gives us interesting information about his second ‘Columba domestica major’, which is clearly marked as a ‘runt’ in the above plate XXXIV:

The greater tame Pigeon, called in Italian, Tronfo & Asturnellato; in English, a Runt ; a name (as I suppose) corrupted from the Italian Tronfo: Though to say the truth, what this Italian word Tronfo signifies, and consequently why this kind of Pigeon is so called, I am altogether ignorant. Some call them Columbae Russicae, Russia-Pigeons, whether because they are brought to us out of Russia, or from some agreement of the names Runt and Russia, I know not. These seem to be the Campania Pigeons of Pliny. They vary much in colour, as most other Domestic Birds: Wherefore it is to no purpose to describe them by their colours. In respect of magnitude they are divided into the biggest and the lesser kind. The greater are more sluggish birds, and of slower flight; the same perchance with those Gesner saith he observed at Venice, which were almost as big as Hens. The lesser are better breeders, more nimble, and of swifter flight. Perchance these may be the same with those, which Aldrovandus tells us are called by his Country men Colombe sotto banche, that is, Pigeons under Forms or Benches, from their place; of various colours, and bigger than the common wild Pigeons inhabiting Dove-cotes.[25]

The Sottobanco pigeon, a breed which was indeed well known to Aldrovandi for it was present in the countryside around Modena from at least the second half of the sixteenth century, is one of the ten officially recognised Italian pigeon breeds.[26] As Willughby implies, it gained its name from its nesting habit – locating its nests under tables in the Modena region.[27] Pizzuti Piccoli describes it as follows: ‘a pigeon rather high on the legs, with proud bearing, horizontal body and slightly raised tail. The head is robust, slightly flattened at the top, with a broad and moderately ascending forehead. The back of the head, the nape of the neck, is adorned with a thick shell-shaped tuft’.[28] Unfortunately this remnant of a pigeon known to Aldrovandi is now threatened with extinction.[29]

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XXXV: Doves and pigeons.

Willughby and Ray provided their readers with a wealth of material on doves and pigeons, beautifully depicted in Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676). Some of these images were based on older authorities such as Aldrovandi, and certainly Willughby included Gessner’s comments on ‘Columba Livia’ (though no illustration), which, as Donegan has noted, was a stock dove.[30]

But Willughby and Ray also provided their readers with much more than recitations of past sources for they were also keen to provide eye-witness accounts. Their description of a turtle dove demonstrates their commitment to providing as scientific an analysis as possible, one which was clearly based on their own study and dissection of the bird:

The Male, which we described from Bill-point to Tail-end was twelve inches long: from tip to tip of the Wings extended twenty one broad: Its Bill slender, from the tip to the angles of the mouth almost an inch long, of a dusky blue colour without, and red within: Its Tongue small and not divided: The Irides of its Eyes between red and yellow. A circle of naked red flesh encompasseth the Eyes as in many others of this kind. Its Feet were red; its Claws black; its Toes divided to the very bottom. The inner side of the middle Claw thinned into an edge. Its Head and the middle of its Back were blue or cinereous, of the colour of a common Pigeon. The Shoulders and the Rump were of a sordid red: The Breast and Belly white: The Throat tinctured with a lovely vinaceous colour. Each side of the Neck was adorned with a spot of beautiful feathers, of a black colour, with white tips. The exteriour quil-feathers of the Wings were dusky, the middle cinereous; the interiour had their edges red. The second row of Wing-feathers was ash-coloured, the lesser rows black. The Tail was composed of twelve feathers; of which the outmost had both their tips and exteriour Webs white. In the succeeding the white part by degrees grew less and less, so that the middlemost had no white at all. The length of the Tail was four inches and an half. Its Testicles were great, an inch long: Its Guts by measure twenty six inches: Its blind Guts very short. Its Crop great, in which we found Hemp-seed: Its Stomach or Gizzard fleshy. Above the stomach the Gullet is dilated into a kind of bag, set with papillary Glandules.[31]

But sometimes even Willughby and Ray could get things wrong! At the end of plate XXXV, we see what they call ‘Oenas Aldr. The Wood Pigeon’. This, as Donegan has noted, is the same bird called ‘Oncas sue vinago’ in Jonstonus’s plate 32 above, and is a stock dove.[32] Willughby conflates stock doves and wood pigeons and describes his stock dove as follows:

It is as big or bigger than a common Pigeon. The Cock weighed fourteen ounces and an half, was from Bill to Tail fourteen inches long, and between the tips of the Wings extended twenty six broad. The colour and shape of the body almost the same with that of a common Pigeon: The Bill also like, and of equal length, of a pale red colour. The Nosthrils were great and prominent. The top of the Head cinereous. The Neck covered with changeable feathers, which as they are variously objected to the light, appear of a purple or shining green; no Silk like them. The fore-part of the Breast, the Shoulders and Wings are dashed with a purplish or redwine colour, whence it took the name [Oenas.] The Wings, Shoulders, and middle of the Back are of a dark ash-colour, the rest of the Back to the Tail of a paler. All the quil-feathers (except the four or five outmost, which are all over black, with their edges white) have their lower part cinereous, and their upper black. The Tail is five inches long, made up of twelve feathers, having their lower parts cinereous, their upper for one third of their length black. The nether side of the body, excepting the upper part of the Breast, is all cinereous. The Wings closed reach not to the end of the Tail. In both Wings are two black spots, the one upon two or three quil-feathers next the body, the other upon two or three of the covert feathers incumbent upon those quils: Both spots are on the outside the shafts, and not far from the tips of the feathers. The two outmost feathers of the Tail have the lower half of their exteriour Vanes white. The Feet are red, the Claws black: the Legs feathered down a little below the Knees. The blind Guts very short. It had no Gall-bladder that we could find; a large Craw, full of Gromil seeds, &c. It had a musculous Stomach, long Testicles; and a long Breast-bone.[33]

As Svensson et al. note, stock doves are actually smaller, and have a shorter tail than wood pigeons.[34]

Sir Robert Sibbald (1641–1722), writing a few year later in his Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684), clearly owed much to Willughby and Ray in his division of pigeons and doves – and therefore makes the same mistake. He divides them between ‘Columba Domestica, or Vulgaris, the Common Pigeon or Dove’, and wild pigeons. The former, he declared, ‘either has bare feet and is of greater or less size, or had feathered feet, being of the larger size, and crested of the lesser size’ while wild pigeons were divided into ‘Turtur [the Turtle Dove]; Palumbus torquatus [the Ring Dove]; Oenas or Vinago, the Stock Dove or Wood Pigeon; and Columba Rupocola [the Rock dove]’.[35]

Wood Pigeon; Phibsborough, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

This wood pigeon (in Irish ‘Colm coille’), as the name suggests, likes to breed in woods, arable farmlands and gardens but may also be found in city centres.[36] This one was spotted by Derek O’Reilly in Phibsborough, Dublin. It is bigger than feral pigeons and had a large white patch on its neck.[37] The good news is that wood pigeons are doing well in Ireland – BirdWatch Ireland states that it is ‘one of Ireland’s top 20 most widespread garden birds’.[38] Under the EU Birds Directive, which ‘aims to protect all naturally occurring wild bird species present in the EU and their most important habitats’, it is a protected species.

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Anon., ‘Stock Dove’, BirdWatch Ireland, 2025.

Anon., ‘Stock Dove’, National Biodiversity Data Centre, 2025.

Anon., ‘Wood Pigeon’, BirdWatch Ireland, 2025.

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Donegan, Thomas M., ‘The pigeon names Columba livia, ‘C. domestica’ and C. oenas and their type specimens’, Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club, 136, no. 1 (2016), 14–27.

Donegan, Thomas M., ‘Supplementary Materials to: “The pigeon names Columba livia, ‘C. domestica’ and C. oenas and their type specimens”, Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 136 (1): 14–27’, www.researchgate.net (2016), 1–45.

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

McCann, John, ‘The Truth about Dovecotes’, online blog.

McCann, John, ‘Dovecotes and Pigeons in English Law’, Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society, 44 (2000), 25–50.

Manco, Jean, ‘Researching the history of dovecotes’, Researching Historic Buildings in the British Isles.

Morgan, J. E., ‘An emotional ecology of pigeons in early modern England and America’, Environment and History, 28, no. 3 (2022), 435–52.

Moss, Stephen, Ten birds that changed the world (London, 2023).

Mullens, W. H., ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, British Birds, 6, no. 2 (1912), 34–57.

Pizzuti Piccoli, Antonio, ‘Conservation of Italian Autochthonous Domestic Pigeon Breeds’, International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, 5, no. 2 (2020), 282–95.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, volume III, Books 8–11, translated by H. Rackham (Cambridge, Mass, 2006).

Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022).

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

Woodlock, Amelie Bias, ‘The sport and art of pigeon racing’, The Liberty (6 May 2024).

__

[1] Quoted in Donegan, Thomas M., ‘Supplementary Materials to: “The pigeon names Columba livia, ‘C. domestica’ and C. oenas and their type specimens”, Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 136 (1): 14–27’, www.researchgate.net (2016), 5.

[2] Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 313.

[3] Ibid., p. 314.

[4] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, volume III, Books 8–11, translated by H. Rackham (Cambridge, Mass, 2006), p. 363.

[5] Pizzuti Piccoli, Antonio, ‘Conservation of Italian Autochthonous Domestic Pigeon Breeds’, International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, 5, no. 2 (2020), 283.

[6] Ibid., 282.

[7] Moss, Stephen, Ten birds that changed the world (London, 2023), p. 62.

[8] Pizzuti Piccoli, ‘Conservation of Italian Autochthonous Domestic Pigeon Breeds’, 283.

[9] Woodlock, Amelie Bias, ‘The sport and art of pigeon racing’, The Liberty (6 May 2024).

[10] Donegan, Thomas M., ‘The pigeon names Columba livia, ‘C. domestica’ and C. oenas and their type specimens’, Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club, 136, no. 1 (2016), 19.

[11] Pizzuti Piccoli, ‘Conservation of Italian Autochthonous Domestic Pigeon Breeds’, 283.

[12] Anon., ‘Stock Dove’, National Biodiversity Data Centre, 2025.

[13] Anon., ‘Stock Dove’, BirdWatch Ireland, 2025.

[14] Donegan, ‘Supplementary Materials’, 6.

[15] Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657), pp 176–7. This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

[16] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 180. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[17] Ibid., p. 180.

[18] Ibid., p. 181.

[19] Manco, Jean, ‘Researching the history of dovecotes’, Researching Historic Buildings in the British Isles. On this see also Morgan, J. E., ‘An emotional ecology of pigeons in early modern England and America’, Environment and History, 28, no. 3 (2022), 8; and McCann, John, ‘Dovecotes and Pigeons in English Law’, Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society, 44 (2000), 35.

[20] McCann, John, ‘The Truth about Dovecotes’, online blog.

[21] Morgan, ‘An emotional ecology of pigeons in early modern England and America’, 4.

[22] Quoted in ibid., 6.

[23] Donegan, ‘Supplementary Materials’, 22, 24.

[24] Ibid., 22.

[25] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 181.

[26] Pizzuti Piccoli, ‘Conservation of Italian Autochthonous Domestic Pigeon Breeds’, 286.

[27] Ibid., 286.

[28] Ibid., 286–7.

[29] Ibid., 288.

[30] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, p. 186; Donegan, ‘Supplementary Materials’, 9.

[31] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, pp 183–4.

[32] Donegan, ‘Supplementary Materials’, 9.

[33] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 185.

[34] Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022), p. 222.

[35] Mullens, W. H., ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, British Birds, 6, no. 2 (1912), 41.

[36] Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, p. 222.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Anon., ‘Wood Pigeon’, BirdWatch Ireland, 2025.