Waterbirds

‘Water-fowl are either Cloven-footed, which are much conversant in or about waters, and for the most part seek their Food in watery places. [Almost all these have long Legs, naked or bare of feathers for a good way above the Knees, that they may more conveniently wade in waters] or Whole-footed, which swim in the water, and are for the most part short-leg’d’.[1]

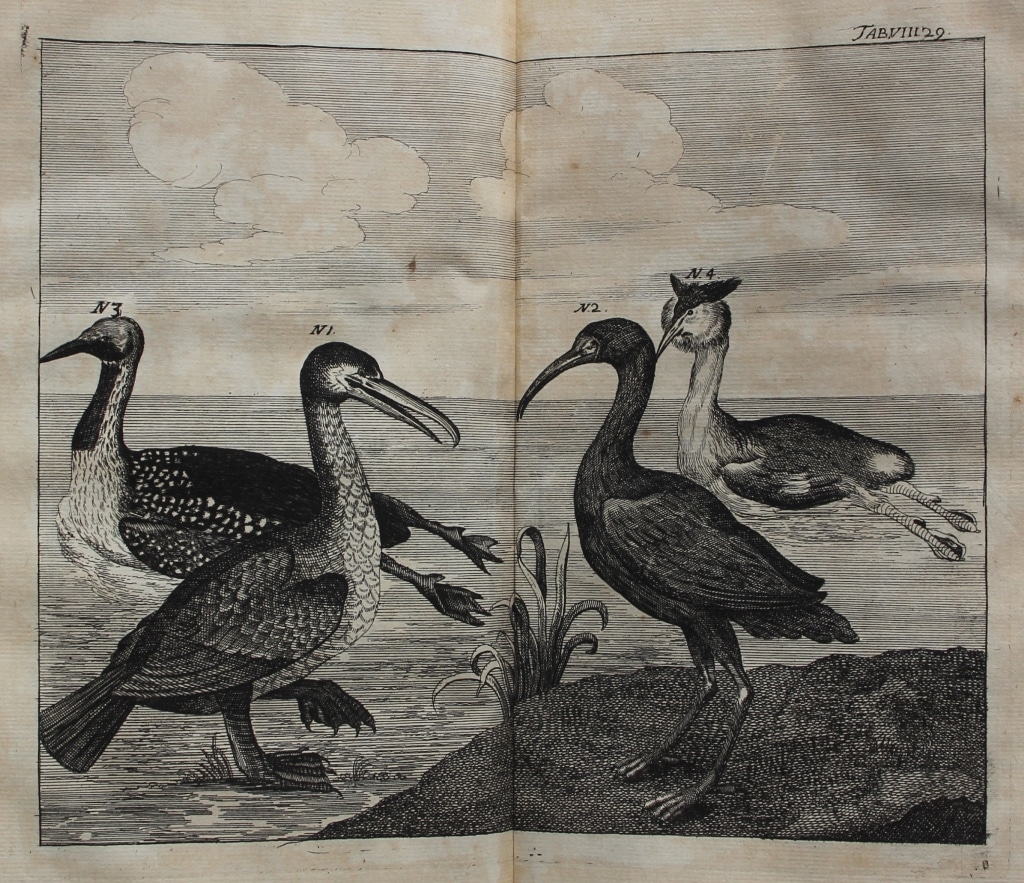

Basilius Besler, Rariora Musei Besleriani quae olim Basilius et Michael Rupertus Besleri collegerunt, aeneisque tabulis ad vivum incisa evulgarunt: nunc commentariolo illustrata a Johanne Henrico Lochnero, ut virtuti toy makaritoy exstaret monumentum, denuo luci publicae commisit et laudationem ejus funebrem adjecit maestissimus parens Michael Fridericus Lochnerus (Nuremberg, 1716), Tab. 8: Group of waterbirds (from left to right: Great Northern Diver; Cormorant; Glossy Ibis, Great-crested Grebe).

As the above quotation from Francis Willughby (1635–72), and John Ray (1627–1705), demonstrates, terminology concerning waterfowl and waterbirds has changed since the seventeenth century. Today ‘waterfowl’ is used in a more limited way to encompass swans, ducks and geese, but in the late seventeenth century it was used in the same way as we would use ‘waterbirds’ – i.e. as an umbrella term for all aquatic birds, whether they lived close to or in water. In the above image we see a selection of waterbirds from a work dedicated to the collections of two noted medical practitioners in Nuremberg, the apothecary Basil Besler (1561–1629) and his nephew Michael Rupertus Besler (1607–61), who was both an apothecary and a physician. The text, by another physician based in Nuremberg, Michael Friedrich Lochner (1662–1720), brought together collections from their Wunderkammer and included in them were a number of birds. In the above plate we see four of them: three waterbirds, a Great Northern Diver (N3), a Great-crested Grebe (N4), a Cormorant, (N1), and also a wader: Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus (N2).

Left: Great Northern Diver, Gavia immer (Brünnich, 1764), NMINH:1880.833.1. © NMI; centre: Great-crested Grebe; Vartry, Wicklow (c) Derek O’Reilly; right: Glossy Ibis, Plegadis falcinellus (Linnaeus, 1766), NMINH:1914.233.1. © NMI

Willughby and Ray, who provide the most extensive scientific classification of waterbirds divided them as follows:

Those that live much about waters are either, first, of great size, the biggest of this kind, having each something singular, and being not reducible to any other tribe, which therefore as straglers and anomalous birds we have placed by themselves, though they agree in nothing but their bigness: Or secondly, of lesser size. These lesser are either Piscivorous, or such as suck a nourishing fat juice or moisture out of muddy and boggy ground, or Insectivorous. The Piscivorous are Herons, Storks, &c. The Limosugae or Mud-suckers may be distinguished by their Bills into such as have very long Bills, either crooked, as the Curlew, or streight, as the Woodcock. The Insectivorous Waterbirds have either Bills of a middle size for length, as the Himantopus; or short Bills, as the Plover, Lapwing, &c.[2]

They began by investigating one of the largest waterbirds, cranes, which they noted were ‘common in the Fens of Lincolnshire, and in Cambridgeshire’, and they then moved on to that ‘great destroyer of fish’, the heron, before finishing with the Bittern, last within what they called the ‘Greater Kind’ of ‘CLOVEN-FOOTED, such as live about waters, and frequent watery places’ of Waterbirds.[3]

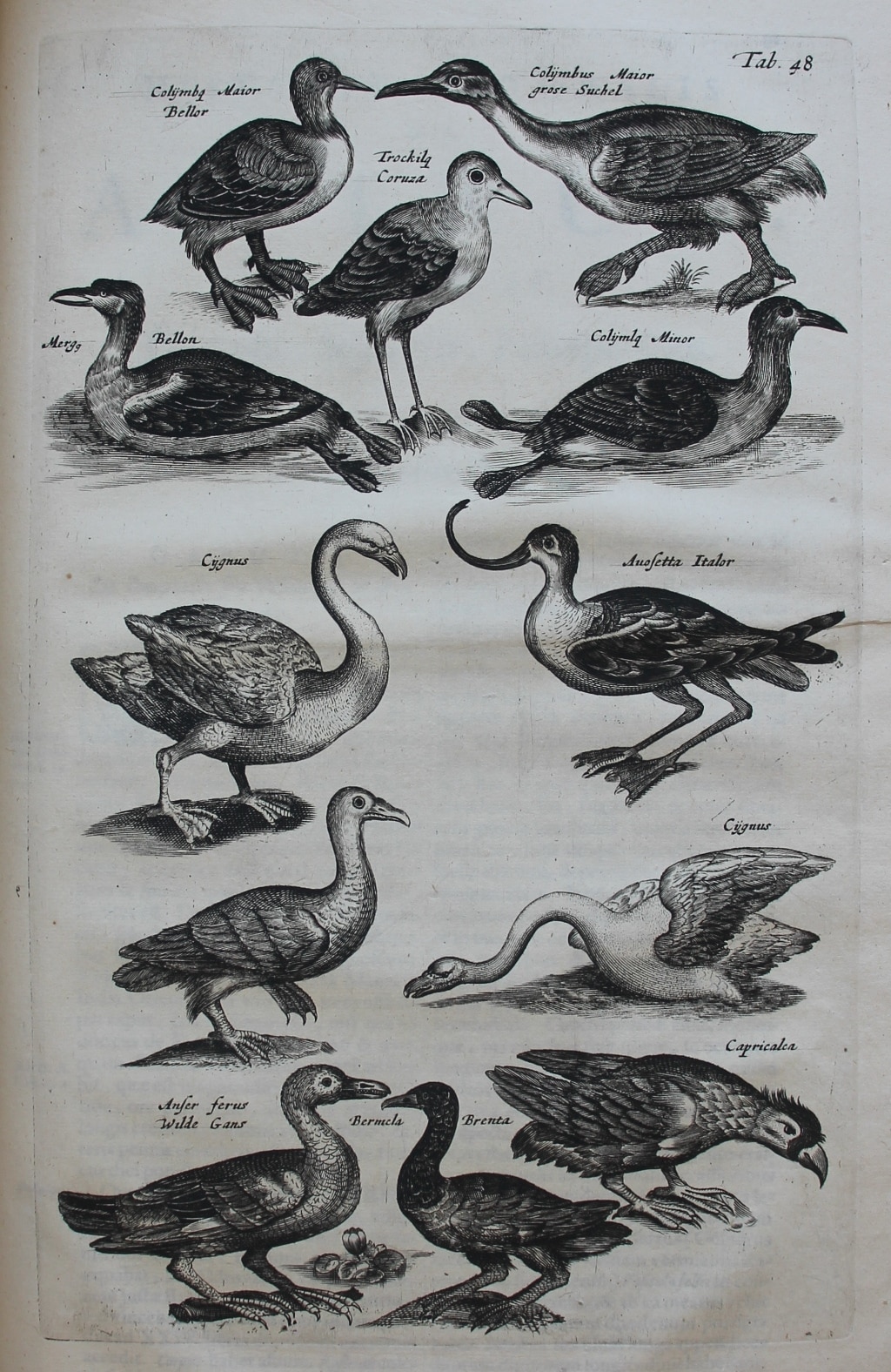

Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), Tab. 48: Waterbirds, including waterfowl and waders.

In this composite plate Joannes Jonstonus (1603–75), brings together waterfowl such as swans and a Brent Goose, as well as waders such as avocets (among others). He, like Willughby and Ray, was also interested in cranes and drew attention both to their triangular flight pattern, and (drawing on medieval sources), the way cranes protected themselves:

When they fly, they keep a triangular sharp angled figure, that they may the easier pierce through the Ayr that is against them. That Crane that gathers the rest together, will correct them, as Isidorus saith. When one is hoarse, another succeeds. When they light upon the Earth to feed, the Captain of them holds up his head to keep watch for the rest, and they feed securely. Before they take rest, they appoint another Sentinel, who may stand and ward with his neck stretched forth, whilest the rest are asleep, with their heads under their wings, and standing upon one leg. The Captain goes about the Camp, and if there be any danger, he claries. Lest they should sleep too soundly, they stand upon one foot, and hold a stone in the other above ground, that if at any time being weary they should be oppressed with sleep, the stone falling might awaken them. They love their young ones so much, that they will fight whether shall give them their breeding. Albertus saw a male-Crane cast down a female and kill her, giving her eleven wounds with his bill, because she had drawn away his young ones from following of him. This fell out at Colen, where tame Cranes use to breed.[4]

Brent Goose; Bull Island, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Willughby and Ray had viewed both live and stuffed specimens of a Brent Goose Branta bernicla: they had seen Brent Geese living in the royal wild-fowl collection in St James’s Park and stuffed geese had been on view at Brignall in Yorkshire at the home of ‘Mr. Johnson’. In addition, Ray had been sent a stuffed specimen by a ‘Mr. Jessop’, also from Yorkshire.[5] ‘Mr. Johnson’ was the same Ralph Johnson (bap. 1629, d. 1695), vicar of Brignall, County Durham, who had sent Ray a Mountain Finch, while ‘Mr. Jessop’ was none other than Francis Jessop of Sheffield, who would later act as Ray’s executor.[6] Willughby and Ray were thus in a good position to provide their readers with a scientific analysis:

It is a little bigger than a Duck, and longer-bodied. The Head, Neck, and upper part of the Breast are black. But about the middle of the Neck on each side is a small spot or line of white, which together appear like a ring of white. The Back is of the colour of a common Goose, that is, a dark grey. Toward the Tail it is darker coloured: But those feathers which are next and immediate to the Tail are white. The lower Belly is white: The Breast of a dark grey: The Tail and greater quils of the Wings black, the lesser of a dark grey. The Bill is small, black, an inch and half long, thicker at the head, slenderer toward the tip: The Eyes hazel-coloured: The Nosthrils great: The Feet black, having the back-toe. The length of the Bird from Bill to Tail was twenty inches.[7]

They rightly concluded that there was a difference between a Brent Goose and a Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis, geese which, they noted, had often been conflated by previous authors.[8]

Pied Avocet Recurvirostra avosetta Linnaeus, 1758, NMINH:1929.48.1. © NMI

When it came to a wader such as a Pied Avocet, Recurvirostra avosetta, a bird Willughby and Ray included in their section on ‘Whole-footed long-leg’d Birds’, they used not only national but also international information, noting that while avocets frequented the coasts of Suffolk and Norfolk in Winter, they had also, on their foreign travels, had a chance to see ‘many of these birds both at Rome and Venice’.[9] It was, given its distinctive bill, an easy bird to spot. They described the avocets they had encountered in Italy in much detail, noting its size and distinctive bill:

In bigness it somewhat exceeds a Lapwing, weighing ten ounces and an half; being extended in length from the tip of the Bill to the end of the Toes twenty three inches and an half; to the end of the Tail but eighteen: In breadth, taken between the tips of the Wings spread, it is full thirty one inches. The Bill is three inches and an half long, slender, black, flat or depressed, reflected upwards, which is peculiar to this Bird, ending in a very thin, slender, weak point. The Tongue is short, not cloven. The Head is of a mean size, round, like a ball or bullet, black above, (save that the fore part of the Head is sometimes grey) which colour also takes up the upper side of the Neck extending to the middle of it. The colour of the whole under side of the body is a pure snow-white; of the upper side partly white, partly black, viz. the outmost quil-feathers of the Wings are above half way black, the rest white, as are also the feathers of the second row. The rest of the covert-feathers almost to the ridge of the Wing are black, which make a broad bed of black, not directly cross the Wing, but a little oblique. On the Back again it hath two black strakes, beginning from the point of the Shoulder or setting on of the Wing, and proceeding transversly till in the middle of the Back they do almost meet, being thence produced streight on to the Tail. The whole Tail is white, three inches and an half long, made up of twelve feathers. The Legs are very long, of a lovely blue colour, bare of feathers for almost three inches above the Knees. The Claws black and little. It hath a back-toe, but a very small one.[10]

They also dissected the bird, commenting on the smallness of its stomach, the length of its guts, and the feeding difficulties posed by its beautiful bill.[11] Willughby’s attention to detail is clearly visible in his discussion of its wing feathers:

Mr. Willughby describes the Wings thus. The interiour scapular feathers are black, which make a long black spot in the middle of the Back. The covert-feathers of the upper part of the Wing, from the setting on thereof to the first joynt, are white; from the first to the second joynt the lesser covert-feathers are black; from the second joynt to the roots of the greater quil-feathers white again. The first quill or pinion feather is wholly black, the succeeding have by degrees less and less black, till in the eight only the exteriour tip remains black.[12]

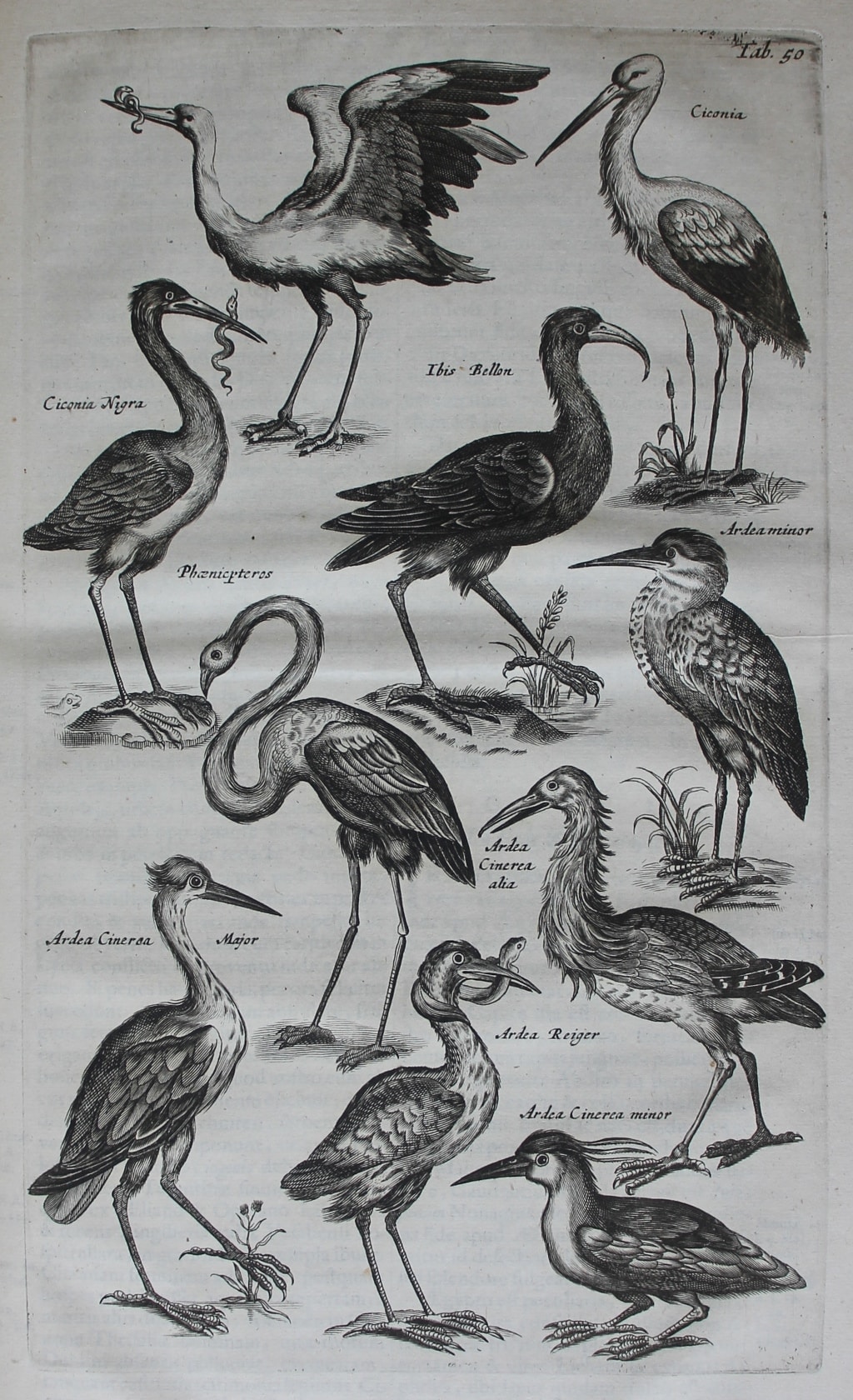

Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), Tab. 50: Herons et al.

Jonstonus presented his readers with an array of herons and other waterbirds but actually had relatively little to say about herons, though he commended their skill as hunters, noting that ‘They lie in wait for fish very cunningly; for they stand so against the Suns beams, that their shadow may not be seen to drive them away: But the Countrey men of Colen say they have such force, that if they put but a foot into the water, they will draw the fish to them as with a bait’.[13] He was much more interested in tales of tame herons, stories which he had gleaned from Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium, for he tells us that ‘Gesner writes, that he read in a German Manuscript, that if their feet be distill’d by descent, and a mans hands be anointed with the oyl, they will come to ones hands that they may be taken’.[14] Jonstonus was always interested in folklore about birds but even he had his limits – he noted that there was a rumour that François I (1494–1547) King of France had reputedly kept a tame heron but cast doubt on whether this was possible, pointing to the fact that Albertus Magnus (d. 1280), had denied that this could be done.[15] Luckily Worth could find out much more about herons not only from his copy of Willughby’s Ornithologia, but also from his beautifully illustrated copy of Luigi Ferdinando Marsili’s Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus: Observationibus Geographicis, Astronomicis, Hydrographicis, Historicis, Physicis (The Hague and Amsterdam, 1726), the fifth volume of which was dedicated to the study of the birds of the Danube. This volume included exceptionally beautiful images of 59 birds and 15 drawings of bird nests, including eggs.

Grey Heron; Donabate, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

The stately heron was commented on by nearly all early modern authorities, but few provided as detailed an account as Willughby and Ray. They started with describing a female heron, ‘The common Heron or Heronshaw: Ardea cinerea major sive Pella’, who, they noted, weighed almost four pounds:

Being from the tip of the Bill to the end of the Claws four foot long, to the end of the Tail thirty eight inches and an half. The foremost feathers on the crown of the Head were white, then succeeded a black crest four inches and an half high. The Chin was white. The Neck being white and ash-coloured was tinctured with red. The Throat white, being delicately painted with black spots; and on its lower part grew small, long, narrow, sharp, white feathers. The Back (on which grows nothing but down) is covered with those long feathers that spring from the Shoulders, and are variegated with whitish strakes or lines tending downwards. The middle part of the Breast, and lower part of the Rump, viz. that underneath the Tail inclines to yellow. Under the Shoulders is a great black spot, from which a black line is drawn to the Vent. The prime feathers of the Wings are about twenty seven in number, the last of which are ash-coloured, all the rest black, excepting the outer edges of the eleventh and twelfth, which are somewhat cinereous. The undersides of all of them is cinereous. The feathers of the bastard Wing are black. Under the bastard-wing is a great white spot. Also white feathers cover the root of the bastard wing above. Then a white line is continued all along the basis or ridge of the Wing as far as its setting on. Ten of the second row of Wing-feathers are black, then four or five have their exteriour borders white: All the rest are ash-coloured. The Tail also is ash-coloured, seven inches long, and made up of twelve feathers. Its Bill is great, strong, streight, from a thick base gently lessening into a sharp point; from the tip to the angles of the Mouth five inches and an half long, of a yellowish green colour. The upper Mandible is a thought longer than the nether, and therein a furrow or groove impressed, reaching from the Nosthrils to the utmost tip. Its sides towards the point are something rough, and as it were serrate, for the faster holding of slippery fishes. The lower Mandible is more yellow: The sides of both are thinned into very sharp edges. The Mouth gapes wide. The Tongue is sharp, long, but not hard. The eye-lids, and that naked space between the Eyes and Bill, are green. The Nosthrils are oblong narrow chinks. The Legs and Feet are green: The hind-part of the Legs and soals of the Feet greener. The Toes very long. The outmost foretoes are joyned to the middle by a membrane below. The inner edge of the middle claw is serrate, which is worthy the notice taking.[16]

They noted that herons like to build their nests at the top of tall trees, and given they had plenty of opportunity, they had dissected the bird.[17]

Stork, Ciconia ciconia (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1902.247.1. © NMI

They were likewise interested in storks and provided their readers not only with their own description of a white stork but also including corroborating information from one of their correspondents, Sir Thomas Browne (1605–82). They considered it to be:

Bigger than the common Heron: Its Neck thicker and shorter than the Herons: Its Head, Neck, and fore-part white: The Rump and outside of the Wings black: The Belly white. The quil-feathers of the Wings black: The Tail white: The Bill long, red, like a Herons Bill. The Legs long, red, bare almost to the Knees or second joynt from the Foot. The Toes from the divarication to the first joynt connected by an intervening membrane. The Vertebres of the Neck are fourteen in number. Its Claws are broad, like the nails of a man.[18]

They noted that their description agreed perfectly with a picture and short description sent them by Browne from Norwich:

It had red Bill and Legs; the Claws of the Feet like humane Nails. The lower parts of both Wings were black, so that when the Wings were closed or gathered up, the lower part of the Back appeared black. Yet the Tail, which was wholly covered and hid by the Wings (as being scarce an inch long) was white, as was also the upper part of the Body. The quills were equal in bigness to Swans quills. It made a snapping or clattering noise with its Bill, by the quick and frequent striking one Chap against the other. It readily eat Frogs and Land-snails which we offered it; but refused Toads.[19]

Jonstonus paid far less attention to the dimensions and description of birds for he was far more interested in what birds could teach humans and his account of storks is particularly interesting in this regard:

They are very chaste and gratefull. One of them in upper Vesalia bade his Host farewel when he departed, and when he return’d, he saluted him again. And not content with a vocall gratitude, he brought him a root of green Ginger. Another pickt out the Eyes of one that lay with his Hostesse when his Host was abroad. Another finding out the adultery of his mate in his absence, brought more company and tore her to pieces. The Stork carries his aged Parents upon his shoulders, and feeds them out of his mouth.[20]

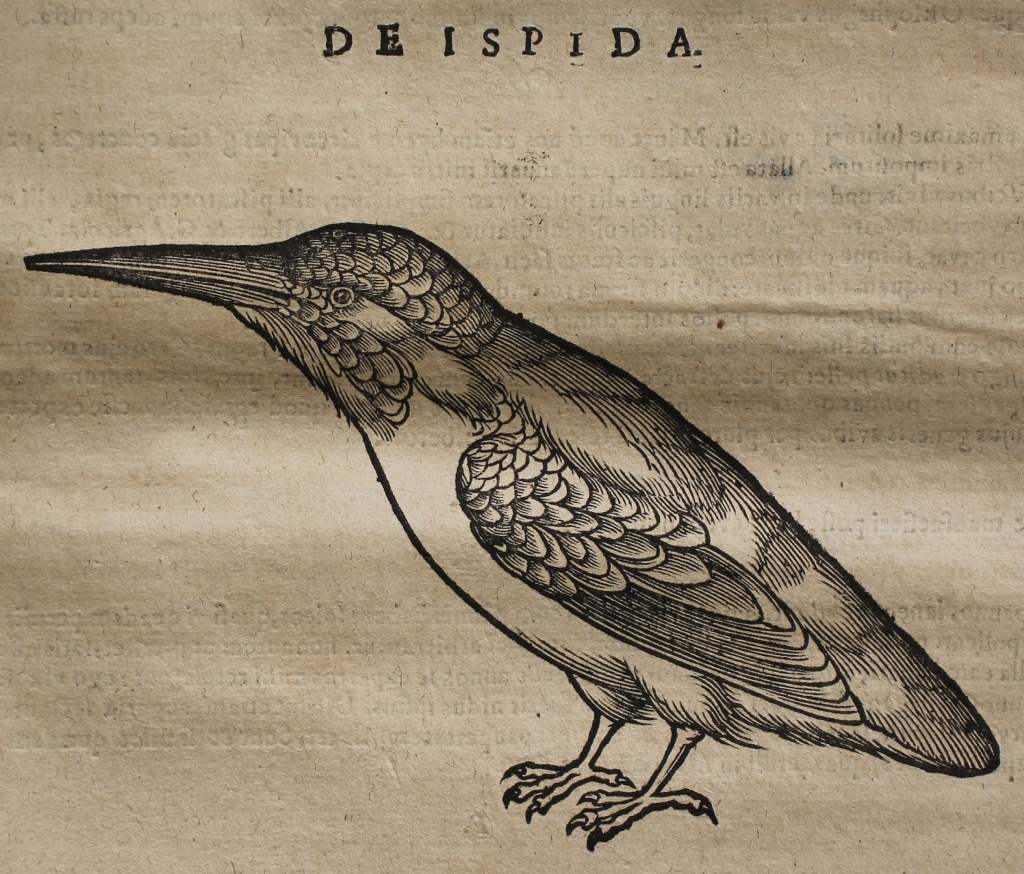

Conrad Gessner, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), Book III, p. 513: Kingfisher.

We see a similar approach in Jonstonus’s account of a kingfisher when he tells us that ‘The Shee of them so loves the Hee, that she is alwaies with him, and in old age carrieth him on her back; and they both die in copulation’.[21] He was citing Plutarch (ca. 45–120), and the rest of his description was heavily dependent on ancient sources such as Pliny the Elder (23/24–79), and Aristotle (384–322 BC). Conrad Gessner (1516–65), had used similar sources but had provided a far more extensive introduction to kingfishers. He explains that this beautiful bird was given the name ‘plumbina’ because it seems to plunge into water to catch fish, much like a piece of lead (plumbina) falling straight down.[22] He owed this information to Giovanni Antonio Clario (fl. 1555), from Eboli, who worked in the Venetian book trade for the publisher Vincenzo Valgrisi (c. 1540-72).[23] Gessner noted that in England it was called ‘kingfisher’ but elsewhere went by a host of different names – for example ‘vitriol’, because of its blue-green colour.[24] His description was based on a personal inspection of the bird (he notes that a bird had recently been brought to him), and he was much taken by the beauty of its colouring.[25] He did not, however, think this bird could be tamed.[26]

Kingfisher; Glasnevin, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–1646).

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Besler, Basilius, Rariora Musei Besleriani quae olim Basilius et Michael Rupertus Besleri collegerunt, aeneisque tabulis ad vivum incisa evulgarunt: nunc commentariolo illustrata a Johanne Henrico Lochnero, ut virtuti toy makaritoy exstaret monumentum, denuo luci publicae commisit et laudationem ejus funebrem adjecit maestissimus parens Michael Fridericus Lochnerus (Nuremberg, 1716).

Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617).

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

Raven, Charles E., John Ray, Naturalist: His Life and Works (Cambridge, 1986).

Schweickard, Wolfgang, ‘Giovan Antonio Menavinoʼs account of his captivity in the Ottoman Empire: a revaluation’, Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie, 132, no. 1 (2016), 180-203.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 273. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., p. 25.

[4] Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657), p. 181. This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

[5] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 360.

[6] Raven, Charles E., John Ray, Naturalist: His Life and Works (Cambridge, 1986), p. 319.

[7] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 360.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., p. 322.

[10] Ibid., p. 321.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Jonstonus, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality, p. 169.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, pp 277–8.

[17] Ibid., p. 278.

[18] Ibid., p. 286.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Jonstonus, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality, p. 178.

[21] Ibid., p. 171.

[22] Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), p. 513.

[23] Schweickard, Wolfgang, ‘Giovan Antonio Menavinoʼs account of his captivity in the Ottoman Empire: a revaluation’, Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie, 132, no. 1 (2016), 185.

[24] Gessner, Historia animalium, p. 513.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.