Clusius on Penguins

The Flemish physician and botanist Carolus Clusius (1526–1609) was one of the first Europeans to comment on penguins in his famous Exoticorum libri decem: quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiæ describuntur: item Petri Bellonii observationes eodem Carolo Clusio interprete (Antwerp, 1605). The news of this ‘new’ flightless bird was almost hot off the press, for the first reports of the bird had come to the Netherlands when a Dutch expedition of 1598 to the Strait of Magellan, led by Jacques Mahu (fl. 1598) and Simon de Cordes (fl. 1598), returned home in 1600, recounting stories of an unusual bird they had encountered on their voyages.[1]

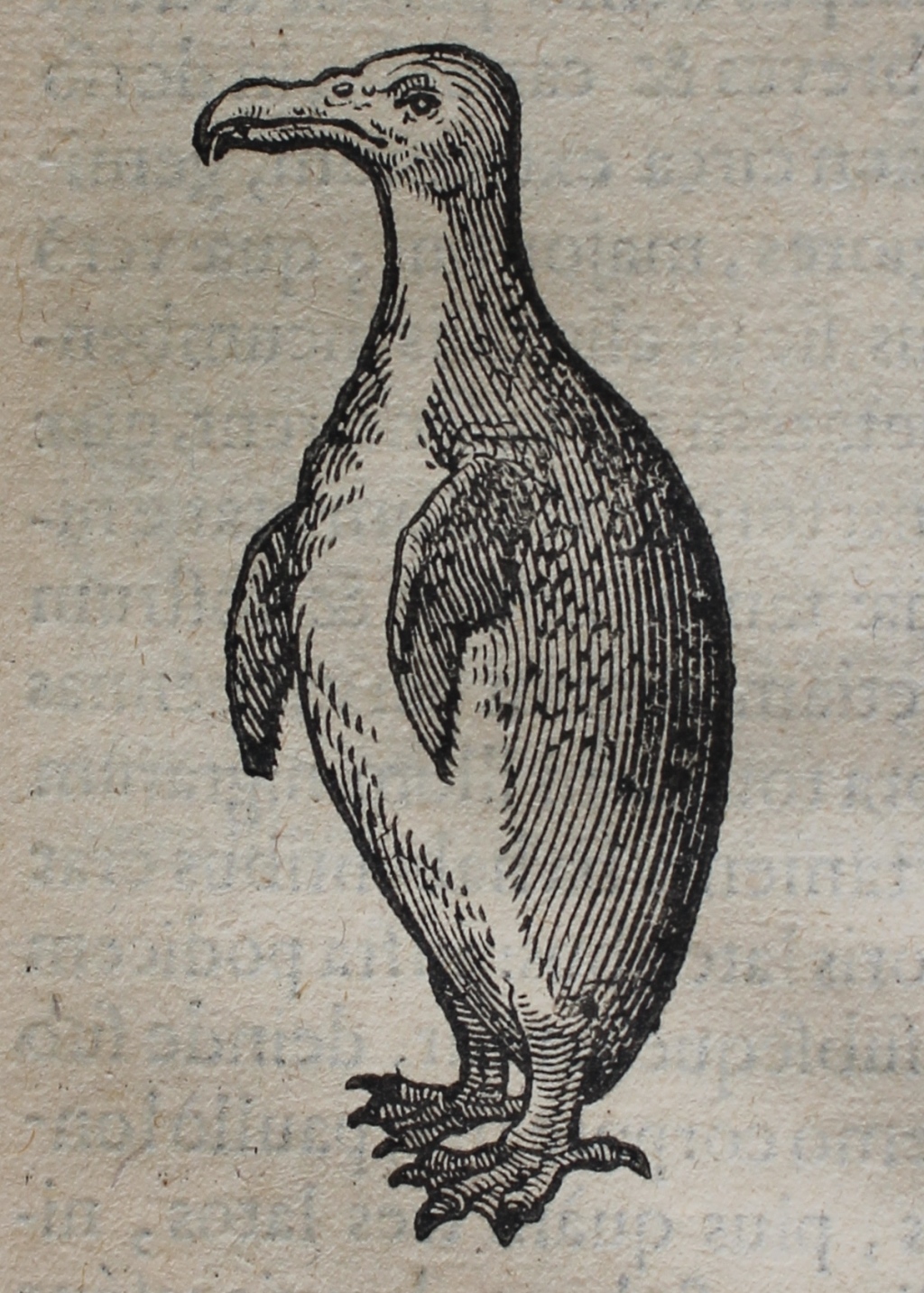

Charles de L’Ecluse (Carolus Clusius), Exoticorum libri decem: quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiæ describuntur: item Petri Bellonii observationes eodem Carolo Clusio interprete (Antwerp, 1605), p. 101: ‘Anser Magellanicus’.

One of these accounts, Wijdtloopigh verhael van tgene de vijf schepen (die int jaer 1598 tot Rotterdam toegherust werden om door de Straet Magellana haren handel te drijven) wedervaren is (Amsterdam, 1600), which was written by the ship’s surgeon Barent Jansz Potgieter (b. 1574), included an image of a penguin and this image subsequently became the source for Clusius’s woodcut of Anser Magellanicus.[2] The Dutch presses, eager for images of flora and fauna of the New World, soon produced more and, as Ommen notes, these portrayed penguins from the Island of Penguins as either having claw-like or webbed feet: as the above image makes clear, Clusius opted for webbed feet.[3] A more detailed image of a penguin may be found in the Libri picturati A. 16–30, a set of beautifully produced images of animals and plants, which were, as Egmont argues, initially collected by Charles de Saint Omer (1533–69), on the advice of Clusius, and which now may be found in Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Kraków, Poland.[4]

Clusius acknowledged that his account was based on the diaries of the sailors, and noted that they called the birds ‘penguins’ because of their fatness (‘pinguis’ in Latin means ‘fat’).[5] Clusius considered the penguin to be a different form of goose and thus called it Anser Magellanicus, ‘Magellan’s goose’. He noted that while they could not fly, they could move swiftly through water and spent most of their time in the water, only coming to dry land to breed.[6] He drew attention to their flat black feet, which, though similar to those of geese were not quite as wide.[7] And, crucially, he makes reference to a collar of white feathers at their neck – a distinguishing characteristic of the Magellanic penguins.[8] Today they are found off the coasts of Argentina, Chile and the Falkland Islands, where their numbers are decreasing due to climate change.[9]

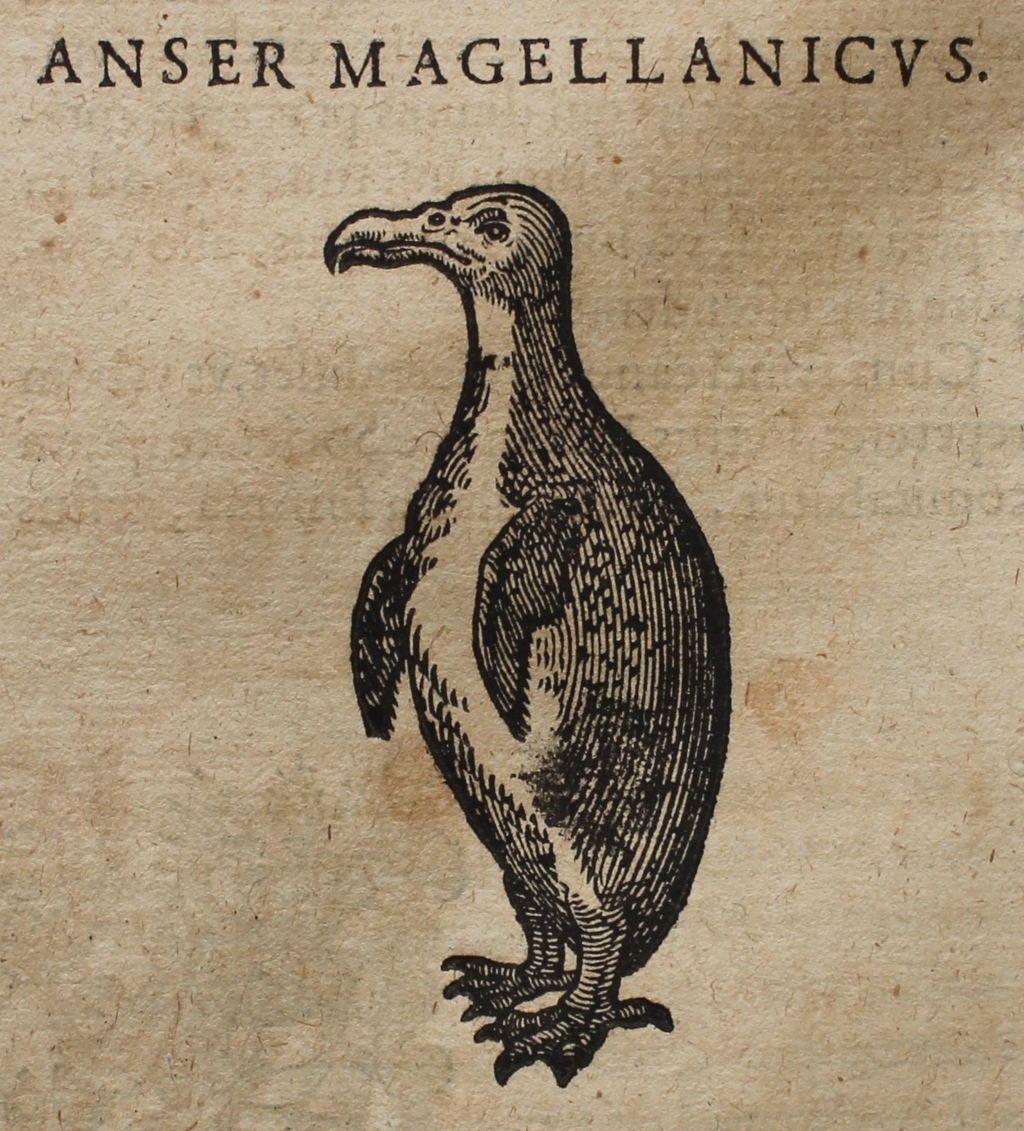

Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae, libris XVI distincta … Accedunt de miris & miraculosis naturis in Europa libri duo; item de iisdem in terra Hebraeis promissa liber unus (Antwerp, 1635), p. 206: ‘Anser Magellanicus’.

Clusius’s image of a penguin soon became iconic, and we can see that the above image, in Worth’s copy of Juan Eusebio Nieremberg’s Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae, libris XVI distincta … Accedunt de miris & miraculosis naturis in Europa libri duo; item de iisdem in terra Hebraeis promissa liber unus (Antwerp, 1635), is in fact a copy of Clusius’s woodcut. The reuse of such woodcuts was common and Nieremberg’s text added little to early modern knowledge of penguins for he replicated Clusius’s account, only adding in one comment, suggesting that they may in fact be the birds without feathers mentioned by ‘Gomara’.[10] Undoubtedly the reference was to the Spanish historian Francisco López de Gómara (1511–64), whose Historia general de las Indias was first printed in Zaragoza in 1552. Nieremberg’s decision to replicate Clusius’s text did not indicate a lack of interest in birds but was simply due to two facts: a) he did not have any first-hand material to add to Clusius’s seminal account; and b) his aim was to produce an encyclopaedic account of the natural history of the New World.

Magellanic penguin, Spheniscus magellaniscus (Forster, 1781), NMINH:1883.30.1. © NMI

Nieremberg (1595–1658), was a Spanish Jesuit who had grown up at the Spanish court at Madrid and who had entered the Colegio Imperial of the Jesuit order in the city. From there he travelled to the University of Salamanca but gave up his studies in civil and canon law to become a member of the Society of Jesus. He became an important voice for the Jesuits, aided in his role as professor of natural history at the Colegio Imperial.[11] There he produced a number of important texts but perhaps none was so widely known as this work, his exploration of the plants and animals of the New World. As Henrickson notes, this encyclopaedic text ultimately owed much to the research of a fellow Spaniard, Francisco Hernandez (1515–87), whose explorations of Mexico had first been partially printed in 1607 and which Worth owned in the famous 1651 edition: Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia a Francisco Hernandez … primum compilata, dein a Nardo Antonio Reccho in volumen digesta, a Io. Terentio, Io. Fabre, et Fabio, Columna Lynceis notis, & additionibus longe doctissimis illustrata. Cui demum accessere, aliquot ex principis Federici Caesii frontispiciis Theatri naturalis phytosophicae tabulae una cum quamplurimis iconibus ad octingentas, quibus singula contemplanda graphice exhibentur (Rome, 1651). Like Hernandez (and many other early modern natural historians interested in ornithology), Nieremberg also proved to be obsessed by Birds of Paradise.

Hendrickson rightly calls Nieremberg a polymath, writing on a host of topics all ultimately aimed at inculcating in his readers an understanding of nature as a sign of God.[12] This motivation is clearly enunciated in his Oculta filosofía, where he states that:

The wonder of nature ought to serve in reverencing its architect, in composing oneself and reforming one’s heart so as to aspire to reach Heaven – all of which can be learned in the same natural world. Everything in it feigns something higher, it all longs for something celestial.[13]

Nieremberg therefore did not look on ornithology (or more generally the study of nature) as an end in itself but as a means to an end. He ultimately viewed his studies (and birds) through the prism of his Jesuit upbringing. By contemplating nature (and in this case the birds of the New World), he hoped that his readers might be led to a deeper understanding of God’s will.

The afterlife of Ole Worm’s ‘Penguin’

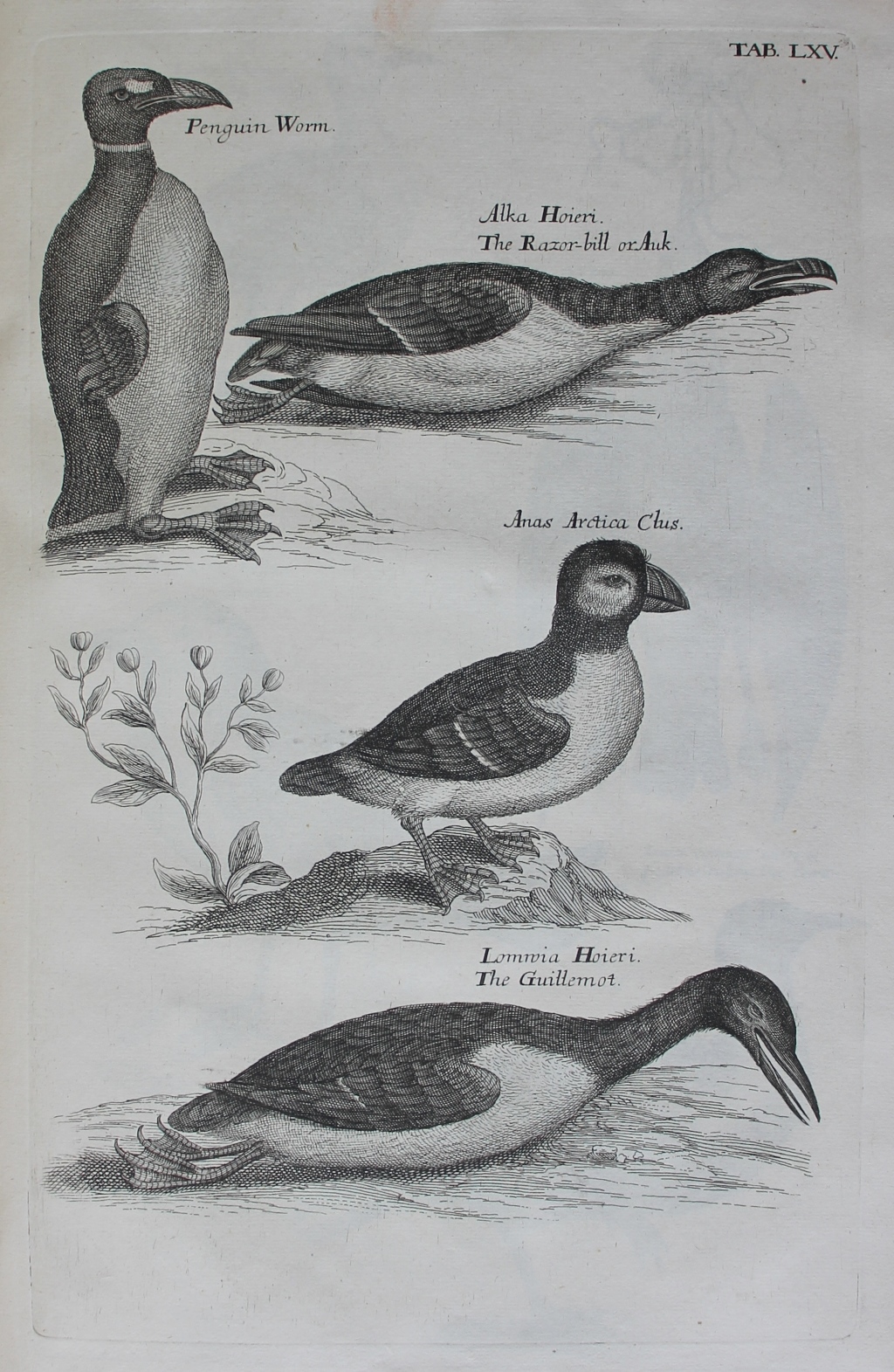

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate LXV: Ole Worm’s ‘penguin’ (actually an auk), a razorbill, a puffin, and a guillemot.

Sometimes the replication of an image or an error in interpretation could lead to misunderstandings and this is nowhere more obvious than in the case of the ‘penguin’ of Ole Worm (1588–1654), a Danish collector whose cabinet of curiosities had been immortalised in Museum Wormianum. Seu Historia rerum rariorum, tam naturalium, quam artificialium, tam domesticarum, quam exoticarum, quae Hafniae Danorum in aedibus authoris servantur (Amsterdam, 1655), a copy of which was also owned by Worth. In it Worm produced two images of what he called a ‘penguin’ and the same image is reproduced (reversed) in Worth’s copy of Willughby’s Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate LXV above.

Worm had mixed up two images of flightless birds which Clusius had included in his Exoticorum libri decem for along with his Magellanic penguin Clusius had been the first to describe (and depict) the great auk, naming it Mergus Americanus. As Valledor de Lozoya et al. note, Clusius had copied his auk from a painting sent to him in 1602 by a French collector of curiosities in Tournai, Jacques Plateau, and the image of the great auk had subsequently been reused by Nieremberg (correctly), in his description of a great auk in 1635.[14] However, when Ole Worm’s collection of curiosities in Copenhagen (Museum Wormianum), was published at Amsterdam in 1655, an error occurred for though Worm also depicted an auk (which he said he had sourced from the Faroe Islands), he captioned it ‘Anser Magellanicus seu Pinguinus’. To add to the confusion, Worm’s auk was depicted as having a ring of white feathers around its neck. As Valledor de Lozoya et al. suggest, this may have been for two reasons – Worm had kept the auk from the Faroe Islands in captivity and it might have been tethered around the neck; or it might have been added as a stylistic flourish to bring it in line with Clusius’s comments concerning the white neck feathers of the true Anser Magellanicus.[15]

As we see in the above plate, it was ‘Penguin Worm’ which was included in Willughby’s Ornithologia of 1676. Willughby and Ray did, however, address the issue, for in their plate they depicted four different birds, labelled (respectively) as ‘Penguin Worm’, ‘Alk Hoieri. The Razor-bill or Auk’, ‘Anas Artica Clus’ (a puffin), and ‘Lommia Hoieri The Guilemot’. It is clear that Willughby and Ray are depicting these birds together because they are related: as BirdWatch Ireland notes, guillemots are the most common species of auks, while puffins are among the smallest species of auks in Ireland.[16] The former may be found around the cost of Ireland (especially at Great Saltee, Co. Wexford) while the latter favour the west coast, especially Skellig Michael, Co. Kerry. The range of the great auk, before it became extinct, was likewise in the northern hemisphere, particularly in the region of Newfoundland.[17]

On right Puffin; Great Saltee Island, Wexford; top left Razorbill and bottom left Guillemot; Howth, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Willughby and Ray were clearly aware of the confusion for they titled their commentary on Worm’s penguin as follows: ‘The Bird called Penguin by our Seamen, which seems to be Hoiers Goifugel’. They report that they had in fact witnessed specimens, both in the Royal Society and in the Tradescant collection at Lambeth, and describe it as follows:

In bigness it comes near to a tame Goose. The colour of the upper side is black, of the under white. Its Wings are very small, and seem to be altogether unfit for flight. Its Bill is like the Auks, but longer and broader, compressed sideways, graven in with seven or eight furrows in the upper mandible, with ten in the lower. The lower Mandible also bunches out into an angle downward, like a Gulls Bill. It differs from the Auks Bill in that it hath no white lines. From the Bill to the Eyes on each side is extended a line or spot of white. It wants the back-toe, and hath a very short tail.[18]

Clearly they wished to make a distinction between this bird and Clusius’s Anser Magellanicus, and their account of the Magellanic penguin therefore closely follows those of Clusius and Nieremberg:

The Birds of this kind, found in the Islands of the strait of Magellane, the Hollanders from their fatness called Penguins … This (saith Clusius) is a Sea-fowl of the Goose-kind, though unlike in its Bill. It lives in the Sea; is very fat, and of the bigness of a large Goose, for the old ones in this kind are found to weigh thirteen, fourteen, yea, sometimes sixteen pounds; the younger eight, ten, and twelve. The upper side of the body is covered with black feathers, the under side with white. The Neck (which in some is short and thick) hath as it were a ring or collar of white feathers. Their skin is thick like a Swines. They want Wings, but instead thereof they have two small skinny fins, hanging down by their sides like two little arms, covered on the upper side with short, narrow, stiff feathers, thick-set; on the under side with lesser and stiffer, and those white, wherewith in some places there are black ones intermixt; altogether unfit for flight, but such as by their help the birds swim swiftly. I understood that they abide for the most part in the water, and go to land only in breeding time, and for the most part lie three or four in one hole. They have a Bill bigger than a Ravens, but not so high; and a very short Tail; black, flat Feet, of the form of Geese feet, but not so broad. They walk erect, with their heads on high, their fin-like Wings hanging down by their sides like arms, so that to them who see them afar off they appear like so many diminutive men or Pigmies. I find in the Diaries [or Journals of that Voyage] that they feed only upon fish, yet is not their flesh of any ungrateful relish, nor doth it taste of fish. They dig deep holes in the shore like Conyburroughs, making all the ground sometimes so hollow, that the Seamen walking over it would often sink up to the knees in those vaults. These perchance are those Geese, which Gomora saith are without feathers, never come out of the Sea, and instead of feathers are covered with long hair. Thus far Clusius, whose description agrees well enough to our Penguin; but his figure is false in that it is drawn with four toes in each foot.[19]

Willughby and Ray then proceed to recount Worm’s own eye witness testimony of his bird (a great auk), pointing out some discrepancies with Clusius’s account:

Olaus Wormius treating of this bird, to Clusius his description adds of his own observation as followeth. This Bird was brought me from the Ferroyer Islands; I kept it alive for some months at my house. It was a young one, for it had not arrived to that bigness as to exceed a common Goose. It would swallow an entire Herring at once, and sometimes three successively before it was satisfied. The feathers on its back were so soft and even that they resembled black Velvet. Its Belly was of a pure white. Above the Eyes it had a round white spot, of the bigness of a Dollar, that you would have sworn it were a pair of Spectacles, (which Clusius observed not) neither were its Wings of that figure he expresses; but a little broader, with a border of white. Whether it hath or wants the back-toe neither Clusius nor Wormius in their descriptions make any mention. In Wormius his figure there are no back-toes drawn.[20]

If there was any doubt, Worm’s own testimony – that he had acquired his bird from the Faroe Islands – would alone have made it clear that he was not dealing with Magellanic penguins, which are found in the southern hemisphere. Instead, he had sourced his bird exactly where great auks could be located in the early modern period: ‘the cold water of the North Atlantic’.[21] Unfortunately they may be found there no longer, for great auks, like their more famous avian flightless counterparts, the dodo, have long been extinct – each species a victim of human activities. The very fact that both species were unable to fly made them vulnerable when humans came calling. The last known pair of great auks were killed on Eldey Island, southwest of Iceland, in 1844. As Iglésias and Fournier-Sowinski note, ‘The intensive hunting pressure exerted on the great auk throughout history is responsible for the collapse of its populations as demographic reconstructions obtained from ancient DNA indicate’.[22]

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Anon., ‘Magellanic Penguin: Spheniscus magellanicus’: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Anon., ‘Guillemot’ on BirdWatch Ireland website, accessed 29 July 2025.

Anon., ‘Puffin’ on BirdWatch Ireland website, accessed 29 July 2025.

Burghartz, Susanna, ‘Apocalyptic Times in a “World without End”: The Straits of Magellan around 1600’, in Puff, Helmut, Ulrike Strasser and Christopher Wild (eds), Cultures of Communication: Theologies of Media in Early Modern Europe and beyond (Toronto, 2017), pp 228–48.

Egmond, F., ‘Clusius, Cluyt, Saint Omer: The origins of the sixteenth-century botanical and zoological watercolours in the Libri Picturati A. 16-30’, Nuncius: Journal of the history of science, 20, no. 1 (2005), 11–67.

Fuller, Errol, The Greak Auk: The Extinction of the Original Penguin (Boston, 2003).

Hendrickson, D. Scott, ‘Juan Eusebio Nieremberg’, in Hendrickson, D. Scott, Jesuit Polymath of Madrid: The Literary Enterprise of Juan Eusebio Nieremberg (1595–1658) (Leiden, 2015), pp 9–50.

Hendrickson, D. Scott, ‘Contemplating the Book of Nature’, in Hendrickson, D. Scott, Jesuit Polymath of Madrid: The Literary Enterprise of Juan Eusebio Nieremberg (1595–1658) (Leiden, 2015), pp 86–125.

Hume, Julian, ‘The history of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius’, Historical Biology, 18, no. 2 (2006), 65–89.

Iglésias, Samuel P., and Jérôme Fournier-Sowinski, ‘An account of the natural history and exploitation of the great auk (Pinguinus impennis) in ‘Histoire des pesches’, an illustrated eighteenth-century manuscript’, Archives of Natural History, 51, no. 2 (2024), 234–52.

Mason, Peter, Before Disenchantment: Images of exotic animals and plants in the early modern world (London, 2009).

Nieremberg, Juan Eusebio, Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae, libris XVI distincta … Accedunt de miris & miraculosis naturis in Europa libri duo; item de iisdem in terra Hebraeis promissa liber unus (Antwerp, 1635).

Ommen, Kasper van, The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609: Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009. With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond (Leiden, 2009).

Paris, Jolyon C., The dodo and the solitaire: a natural history (Bloomington, Indiana, 2013), kindle edition.

Patiño Loira, Javier, ‘Curiosity and Artifice in Juan Eusebio Niermberg’s Natural Philosophy’, Humanities, 14, no. 54 (2025) 1–13.

Valledor de Lozoya, Arturo, David González Garcia and Jolyon Parish, ‘A great auk for the Sun King’, Archives of Natural History, 43, no. 1 (2016), 41–56.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] As Burghartz notes, though the Straits of Magellan had been discovered in 1520, the end of the sixteenth century witnessed a colonial struggle between Spain, Portugal, England and the Netherlands, each interested in controlling this important sea route: Burghartz, Susanna, ‘Apocalyptic Times in a “World without End”: The Straits of Magellan around 1600’, in Puff, Helmut, Ulrike Strasser and Christopher Wild (eds), Cultures of Communication: Theologies of Media in Early Modern Europe and beyond (Toronto, 2017), p. 228.

[2] Ommen, Kasper van, The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609: Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009. With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond (Leiden, 2009), p. 95.

[3] Ibid.

[4] On this set see Egmond, Florike, ‘Clusius, Cluyt, Saint Omer: The origins of the sixteenth-century botanical and zoological watercolours in the Libri Picturati A. 16-30’, Nuncius: Journal of the History of Science, 20, no. 1 (2005), 11–67.

[5] L’Ecluse, Charles de (Carolus Clusius), Exoticorum libri decem: quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiæ describuntur: item Petri Bellonii observationes eodem Carolo Clusio interprete (Antwerp, 1605), p. 101.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Anon., ‘Magellanic Penguin: Spheniscus magellanicus’: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2020. Spheniscus magellanicus in 2020 listed their status as ‘least concern’ but noted that numbers were decreasing.

[10] Nieremberg, Juan Eusebio, Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae, libris XVI distincta … Accedunt de miris & miraculosis naturis in Europa libri duo; item de iisdem in terra Hebraeis promissa liber unus (Antwerp, 1635), p. 207.

[11] On Nieremberg’s life see Hendrickson, D. Scott, ‘Juan Eusebio Nieremberg’, in Hendrickson, D. Scott, Jesuit Polymath of Madrid: The Literary Enterprise of Juan Eusebio Nieremberg (1595–1658) (Leiden, 2015), pp 9–50.

[12] Hendrickson, D. Scott, ‘Contemplating the Book of Nature’, in D. Scott Hendrickson, Jesuit Polymath of Madrid: The Literary Enterprise of Juan Eusebio Nieremberg (1595–1658) (Brill, 2015), pp 88 and 90.

[13] Ibid, p. 123

[14] Valledor de Lozoya, Arturo, David González Garcia and Jolyon Parish, ‘A great auk for the Sun King’, Archives of Natural History, 43, no. 1 (2016), 41. See also Mason, Peter, Before Disenchantment: Images of exotic animals and plants in the early modern world (London, 2009), p. 143.

[15] Ibid., 44.

[16] ‘Guillemot’ and ‘Puffin’ on BirdWatch Ireland website, accessed 29 July 2025.

[17] Valledor de Lozoya, et al., ‘A great auk for the Sun King’, 50.

[18] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 322.

[19] Ibid., p. 323.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Fuller, Errol, The Greak Auk: The Extinction of the Original Penguin (Boston, 2003), p. 21.

[22] Iglésias, Samuel P., and Jérôme Fournier-Sowinski, ‘An account of the natural history and exploitation of the great auk (Pinguinus impennis) in ‘Histoire des pesches’, an illustrated eighteenth-century manuscript’, Archives of Natural History, 51, no. 2 (2024), 235.