Belon and Gessner on Finches

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 359: Bullfinch.

Pierre Belon (1517–64), considered bullfinches to be rather corpulent birds, with beautifully coloured plumage.[1] He noted that they were often sighted on their own as they did not live in large flocks.[2] He himself had heard bullfinches ‘singing in the forests of Montboisseur’ and he reported that in Italy, the bird was sighted frequently.[3] There had also been sightings in Bavaria, Bohemia, Saxony and other parts of Germany and these Belon could attest to himself for he had travelled there in the company of Valerius Cordus (1515–44).[4] He and Cordus had studied at the University of Wittenberg together and he mentions that in the early 1540s, they and two others, Gaspar Neuwitz (Naevius) (1514–80), ‘an excellent physician’ who subsequently retired to Leipzig, and Hieronymus Scribonius (d. 1547), a physician at Nuremberg, undertook a series of journeys.[5] He was thus well placed to comment on the regional spread of this colourful bird.

According to Belon, both males and females have a black beak, which is short and slightly hooked.[6] He considered its head to be entirely black, and black also was the predominant colour of its wings though the latter has a lead-coloured line through them. Its long tail was ashen on the back but its chest, throat and belly were red.[7] Its legs too were reddish in colour and it had round black eyes.[8] Belon may had dissected the bird for he notes differences between its tongue and that of other birds.[9]

Bullfinch; Donabate, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Edward Topsell (1572–1625), a Church of England clergyman who produced a number of translations of the Historia animalium of Conrad Gessner (1516–65), and the Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] of the Italian natural historian Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), explains how bullfinches got their name:

This also is a small and wormeating birde called by Aristotle Pyrrhula, an by the Latynes Rubicilla, by the Italians Suffuleno and Stufflotto, and sometimes Franguello montano, and about the Alpes franguel Inuerneng, a winter fynche. By the frenche piuoine and pion, by the Germanes Gutfinck, Brommeiss, Bollenbysser, Bollebick, and Rotuogel, Hail Goll, and Blutfynck, from when cometh our Englishe worde, Bullfynche, for the worde Blutfincke is giuen bycause of the bloud-redd necke it hath … the female is a pale Chesnutt colour on the breast, but the Male, a bright redd like bloud, hauinge a blacke beake very short and broade in forme like a triangle, the tongue broader then any other birdes of that bignes, being at the ende bare, tender, and fleshie, where it tasteth the meate, but vpwarde courered with a thicke skynne like a horne. The backe is of a grayish colour, with some blewns therein, the Crowne of the head, tayle, and types of the Wings blacke: and the wings white next to the belly. Their legs and feete very small and brownishe: the rumpe feathers white vpon blacke quills: and two or three of the longe feathers in the wings are couered with small white feathers. But there onely beauty lyeth in their breast, the vnderpart of their throate and forepart of their belly which is like the purest redd leade or pomegrantate liquor.[10]

William Turner, writing in 1544, noted the ability of the bullfinch to learn a tune: ‘It is the readiest bird to learn, and imitates a pipe very closely with its voice’.[11] This ability, coupled with their striking colouring made bullfinches popular as pets: both Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of Great Britain, and Nicholas II (1868–1918), Emperor of Russia, owned bullfinches.[12] Classifying bullfinches is still difficult for as Birkhead notes, they are quite different from other finches for they bond for life.[13]

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 365: Greenfinch.

Belon tells us that greenfinches are not really green but yellow tinged with green and this accords with the description of Greenfinch Chloris chloris in Collins Bird Guide, which describes the bird as having:[14]

A rather stout body, head and bill. Bill pale pink or ivory-coloured. Recognised by yellow edges to primaries, forming yellow panel on folded wing, by greenish tone to underparts in all plumages, and, in flight, by yellow at base of tail-sides as well as on primaries. Male: Yellowish-green breast, grey-green upperparts, greyish head-side and light grey wing-panel. Much yellow on primaries and tail. Female: Dull grey colours, mantle/back tinged brown, less yellow on wings and tail. Juvenile: Diffusely streaked.[15]

Belon noted that the front of a greenfinch’s head was yellow, with a black line on either side.[16] In the main he attempted to describe a greenfinch in relation to other birds: its short beak he likened to that of a hawfinch in so far as its upper beak was smaller than its lower beak; the colour of its back resembled that of a linnet; its wings were the colour of a goldfinch; its body was longer than that of a bunting.[17] Belon thought that there were two species of greenfinch (his latter one he called a ‘Hedge Greenfinch’), and colour-wise declared that it looked like a cross between a greenfinch and a chaffinch.[18] Its wings were more akin to a Mountain finch than a goldfinch and its head was greener.[19]

Greenfinch; Dursey Island, Cork (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Francis Willughby (1635–72), and John Ray (1627–1705), in The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books (London, 1678), which was an enlarged translation of Worth’s copy of Willughby’s Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), provided a far more detailed analysis of greenfinches, one based on chapter 18 of Book XVIII of Ulisse Aldrovandi’s 3-volume work on birds, which Worth owned in a 1637–46 edition: Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46):

The Green-finch : Chloris, Aldrov. Ornithol. lib. 18. cap. 18. It is bigger than a House-Sparrow; of an ounce and ⅛ weight; of six inches and an half length, measuring from Bill-point to the Feet or Tails end: of ten inches and an half breadth between the extreme terms of the Wings expanded. It is called by some the Green Linnet. Its Bill is like that of the Grosbeak, but much less, of half an inch length, sharp-pointed, and not crooked: The upper Mandible dusky, the nether all whitish. The Tongue is sharp, and as it were cut off, ending in filaments: The Eyes furnished with nictating membranes: The Nosthrils round, situate in the upper part of the Bill next the Head: The Feet of a flesh-colour; the Claws dusky. The outer Toe at bottom sticks fast to the middle one.

The Head and Back are green, the edges of the feathers being grey. The middle of the Back hath something of a Chesnut colour intermingled. The Rump is of a deeper green or yellow: The Belly white: The Breast of a yellowish green: The Throat of the same colour with the Neck: The feathers contiguous to the Bill are of a deep yellowish green. The borders of the outmost quil-feathers of the Wings are yellow, of the middlemost green, of the inmost grey. The inner feathers of the second row are grey, the outer green. All the rest of the covert-feathers of the Wings are green. The feathers along the base or (if you please) ridge of the Wing are of a lovely yellow. The coverts also of the undersides of the Wings are yellow. The Tail is two inches and a quarter long, made up of twelve feathers; of which the two middlemost are all over black, those next have their outer edges yellow: The remaining four on each side from the middle outwardly are black, but all their inner Webs from top to bottom yellow.[20]

To this Willughby and Ray added their own comments, the results of their dissection of a greenfinch and their own observations:

The Liver is divided into two Lobes, and hath a Gall-bladder annexed. The bird we dissected had a large Craw, a musculous stomach, filled with seeds of Plants. It builds in hedges: The outmost part of its Nest is made of hay, grass, or stubble; the middle of Moss; the inmost, on which the Eggs lie, of feathers, wool, and hair. In this Nest it lays five or six Eggs, near an inch long, of a pale green colour, sprinkled with sanguine spots, especially at the blunt end. The colours of the Hen are more languid, not so bright and lively: And on the Breast and Back it hath oblong dusky spots. The Chloris of Aldrovandus, according to his description, seems to be less green than ours. It feeds upon the seed of Rape, Thistles, Docks, and most willingly Canarygrass, as do other birds of this kind.[21]

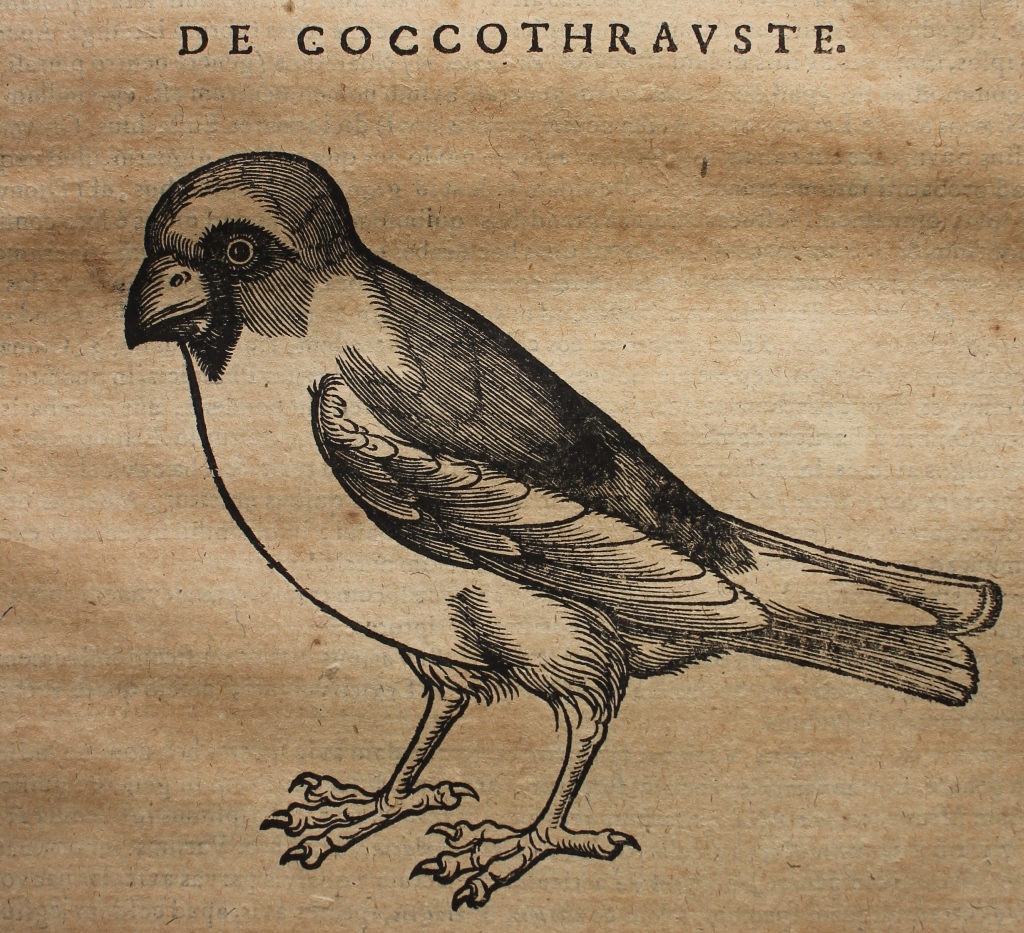

Conrad Gessner, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), p. 242: De Coccothravste – hawfinch.

Conrad Gessner, called hawfinches ‘Coccothraustes’ and concentrated on their large beak, which was used to crack cherry stones and get to the kernel of hard grains.[22] Willughby and Ray’s later seventeenth-century account reflects that of Gessner not only in its description but also in its emphasis on the etymology of the bird’s name:

Of the Gros-beak or Haw-finch, called by Gesner, Coccothraustes. §. 1. The common Gros-beak: Coccothraustes vulgaris. This Bird for the bigness of its body, but especially of its Bill, in which it exceeds all others of this kind, doth justly challenge the first and chief place among thick-billed birds. The French from the bigness of its Bill do fitly call it Grosbec; the Italians, Frisone or Frosone. Hesychius and Varinus of the word [kokkothraustes] write only, that it is the name of a bird, but what manner of bird they do not explain. Gesner observing that name exactly to fit this bird, imposed it upon it.

It is bigger than a Chaffinch by about one third part; short-bodied: Its Head bigger than for the proportion of the body. Its Bill very great, hard, from a broad base ending in a sharp point, of the figure of a Cone or Funnel, half an inch long, having a large cavity within, of a whitish flesh-colour, almost like that of the interiour surface of the mother of Pearl shell, only the tip blackish. The Eyes are grey or ash-coloured, as in Jackdaws. The Tongue seems as it were cut off, as in the Chaffinch. The Feet are of a pale red: The Claws great, especially those of the middle and back-toes. The middle Toe is the longest; the outer fore-toe and the back-toe are equal one to the other.

At the base of the Bill grow Orange-coloured feathers, between the Bill and the Eyes black. The lower Chap in the Males is compassed with a border of black feathers. The head is of a yellowish red, or rusty colour: The Neck cinereous. The Back red, the middle parts of the feathers being whitish. The Rump from yellow inclines to cinereous. The sides and Breast, but especially the sides, are of a mixt colour of red and cinereous. Under the Tail, and in the middle of the Belly the Plumage is whiter. [In another bird the Back was of a grey or ash-colour, tinctured with red: The Head and Throat greenish: The sides and Breast painted with transverse black lines.]

The quil-feathers in each Wing are eighteen in number, of which the nine or ten foremost for half way from the shaft inward are white. The white part from the first inward being dilated. Of the subsequent one half is white, but not so far as the shaft: The three inmost or next the body are red. The tips of all from the second to the tenth shine with a changeable colour of purplish and blue, like the Necks of Pigeons. From the tenth the exteriour borders of the sixth or seventh succeeding are grey, else they are all dusky. The Tail is but short, of about two inches length, composed of twelve feathers, spotted at the top on their interiour Vanes with white, on their exteriour in the middle feathers with red, in the outer with black. [In another bird the middle feathers of the Tail were greenish].[23]

They were likewise interested in where the bird was sighted, its habit and diet:

About Frankefort on the Main, and elsewhere in Germany, and in Italy, it is common. In Summer time it lives in the Woods and Mountains; in the Winter it comes down into the Plains. It seldom comes over to us in England, viz. only in hard Winters. It breaks the stones of Cherries, and even of Olives with expedition, the Kernels whereof it is very greedy of. The Stomach of one we dissected in the Month of December was full of the stones of Holly-berries. It feeds also upon Hemp-seed, Panic, &c. and moreover upon the buds of trees, like the Bulfinch. It is said to build in the holes of trees, and to lay five or six Eggs. It weighs an ounce and three quarters: Is in length from Bill to Claws seven inches and an half; in breadth between the tips of the Wings extended twelve and an half.[24]

Conrad Gessner, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), p. 343: ‘De Fringilla Montana’ – brambling, also known as the mountain finch.

In his discussion of hawfinches, Gessner had noted that around Lake Maggiore they were also known as ‘fringilla montana’ but he later included a separate image of a Brambling Fringilla Montifringilla, noting that, according to his colleague Turner, their English name was ‘Bramling’.[25] He described it as having a yellow beak, with wings of a variety of colours, including white, black and yellow with transverse lines of yellow-black-red, and noted its bluish neck, whitish belly and some red colouring at its breast and throat.[26]

As usual, Willughby and Ray provided an authoritative (and exhaustive) account:

The great pied Mountain-Finch or Bramlin: Montifringilla calcaribus Alaudae seu major. It is equal in bigness to the common Lark, from the tip of the Bill to the end of the Tail being five inches and a quarter long; and between the extremes of the Wings stretched out twelve and three quarters broad. Its Bill is half an inch long, of a yellow colour, with a black tip. The end of the Tongue is divided into filaments. The top of the Head of a fulvous red, darker toward the Bill. [Mr. Johnson attributes to the Head and upper part of the Neck a dusky red or chesnut colour.] The upper side of the Neck, the Rump and sides are also red: So is the Breast, but paler, the rest of the under side, Throat, Belly, Wings, &c. is white. The underside of the Neck, the Back and scapular feathers are elegantly variegated with black and a reddish ash-colour; the middle part of each feather being black, and the outsides red. The black spots appear of a triangular figure. In the upper part of the Wings and bottom of the Back there is more of red.

Each wing hath eighteen prime feathers, of which the eight outmost or longest are black; yet their bottoms, as far as they are hidden by the second row, except the outer edge of the outmost feather are white: Moreover, the very tips, or rather edges of the tips of all excepting the two outmost, are white. The seven next, which take up the middle part of the Wing, are wholly white, save that near the tip on the outside each feather hath an oblong black spot. The remaining three or four next the body are black, having their uppermost edges red. All the covert-feathers of the Wings, excepting those next the body, and two or three, which make up the bastard Wing, are white; those excepted being black. But Nature (as I see) observes not an exact rule in the colours of this birds Wings: For in the bird described by Mr. Willughby the covert-feathers of the black quils were for the most part black, of the white ones white: Yet in general in all birds that we have seen there were large white spaces in each Wing. The Tail is somewhat forked, two inches and an half long, made up of twelve feathers, the two outmost whereof on each side being wholly white, save a very little of the outer edge toward the tip, which is black, more in the outmost, less in the next. The outward Web of the third on each side almost from the top quite down to the bottom is white: The remaining six are black, having only their edges about their tips white. The Legs, Feet, and Claws are cole-black. The back-Claw or Spur is longer than the rest, as in Larks, of about half an inch. The outmost Toe for a good space from the divarication is joyned to the middle one, as in most small birds. This Bird Mr. Willughby found and killed in Lincolnshire.[27]

Ray mentions that a ‘Mr Johnson’ had sent them a Mountain Finch (and a description of it) from Yorkshire:

Mr. Johnson sent us the Bird it self, and the description of it out of the Northern part of Yorkshire. The same Mr. Johnson sent also the description of another bird of this kind by the name of The lesser Mountain-Finch or Bramlin, together with the case of the Bird; which by the case I took to be only the Female of the precedent, he from its difference in bigness, place, and other accidents rather judges it a distinct species. I shall therefore present the Reader with his description of it.

It is of the bigness of a yellow Finch, hath a thick, short, strong Neb, black at the very point, and the rest yellow. All the forehead of a dark chesnut, almost black, growing lighter backwards, about and under either Eye lighter chesnut: The back of the Neck ash-coloured, which goes down the Back to the Tail, but there more spotted with black. Under the Throat white, but Breast and Belly dasht or waved with flame-colour; at the setting on of the Wing grey. The first five feathers blackish brown, all the rest white, save a little dash of brown near the point of each feather. The Tail consists of twelve feathers, the three outmost on either side white, save a little small dash of dark brown: The rest dark brown. The Feet perfectly black. The hind-claw as long again as any of the rest.[28]

The Johnson in question was the naturalist Ralph Johnson (bap. 1629, d. 1695), vicar of Brignall, County Durham, a great friend of Ray’s who describes him in the preface to the 1678 English translation of Ornithologia as living ‘near Greta Bridge in Yorkshire, a Person of singular skill in Zoology, especially the History of Birds, who communicated to us [at my request] his Method of Birds … his judgement concurring with ours in the divisions and characteristic notes of the Genera’.[29]

Brambling, Fringilla montifringilla Linnaeus, 1758, NMINH:1890.62.1. © NMI

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Birkhead, Tim, The Wisdom of Birds: An illustrated history of ornithology (New York, 2008).

Delaunay, Paul, ‘L’aventureuse existence de Pierre Belon, du Mans. Chapitre I. La jeunesse de Pierre Belon’, Revue du seizième siècle, 9, nos. 3–4 (1922), 251–68.

Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617).

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022).

Topsell, Edward, The Fowles of Heauen or History of Birdes, edited by Thomas P. Harrison and F. David Hoeniger (Austin, 1972). Please note that this work is not in the Edward Worth Library.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 358.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.; Delaunay, Paul, ‘L’aventureuse existence de Pierre Belon, du Mans. Chapitre I. La jeunesse de Pierre Belon’, Revue du seizième siècle, 9, nos. 3–4 (1922), 257.

[6] Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, p. 358.

[7] Ibid., p. 359.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Topsell, Edward, The Fowles of Heauen or History of Birdes, edited by Thomas P. Harrison and F. David Hoeniger (Austin, 1972), pp 69–70. Topsell’s work on birds was heavily dependent on that of Aldrovandi. Worth did not collect Topsell’s book.

[11] Quoted in Birkhead, Tim, The Wisdom of Birds: An illustrated history of ornithology (New York, 2008), p. 242.

[12] Ibid., p. 242.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, p. 364.

[15] Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022), p. 394.

[16] Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, p. 365.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 246. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), p. 242.

[23] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, pp 244–5.

[24] Ibid., p. 245.

[25] Gessner, Historiae animalium, pp 242, 343.

[26] Ibid., p. 343.

[27] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 255.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid., Sig. (a)1r.