Waterfowl: Swans, Ducks and Geese

Waterfowl (swans, ducks and geese), classified today as ‘Anatidae’, is a large family made up of some 151–173 species (depending on whether screamers and magpie geese are included).[1] Despite the many different shapes and sizes within the family, all have certain features in common: such as their front three toes being webbed, (useful for their aquatic lifestyle), and a flat broad bill.[2]

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 152: Swan.

Swans fascinated natural historians and these beautiful creatures are included in every book on birds which Worth owned.[3] However, sometimes the swan’s fame militated against an in-depth description for Pierre Belon (channelling Aristotle (384–322 BC)), thought it too familiar to require a lengthy description.[4] Francis Willughby (1635–72), and John Ray (1627–1705), as usual, gave rather more information and discussed two different types of swan: ‘The tame Swan: Cygnus mansuetus’ and ‘A wild Swan, called also an Elk, and in some places a Hooper’.[5] The first is now called Mute Swan (Cygnus olor), and Willughby and Ray noted that it was ‘the biggest of all whole-footed Water-fowl with broad Bills’.[6] They themselves had inspected an old swan that weighed twenty pounds but they were also familiar with younger swans as they include comments about them in their lengthy description.[7] As Cabot notes, Mute Swans are the ‘largest and heaviest flying wildfowl in the world’, and may weigh up to 22.5kg.[8] The swan’s white plumage is not only beautiful – it is also a warning to smaller birds to be make way for them during the breeding season![9]

Mute Swan; Phibsborough, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Belon (1517–64), was interested in both the swan’s outward beauty and inward anatomy, reminding his readers of the importance of dissecting birds in order to recognise differences in bird anatomy.[10] His contemporary, Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), certainly agreed, and included a discussion of their skeleton and organs in the third volume of his massive Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).[11] Joannes Jonstonus (1603–75), who relied heavily on Aldrovandi, synopsised the Italian natural historian’s findings:

The internal constitution of Swans is wonderfull, Aldrovandus dissected them. The Intestines were 14. spans and a hand breadth long; and many of them were covered with fat inwardly, as thick as ones thumb, which served instead of a caul; which being not intricate with many windings and turnings, but onely by a single revolution are turned back into themselves inwardly, with a middle rundle, perchance some of the nutriment might passe by nor distributed; but nature, to help this inconvenience, hath fastened two blind guts; a hands breadth between the anus and their beginning: the right intestine passing between, which should make amends for the windings of the guts that are deficient. The gullet is of a wonderfull structure. For the sharp artery that accompanies the wesand under it, descending to the throat, when it comes there, doth not tend directly to the Lungs as in other Creatures, but is elevated above the chanel bones, and is inserted into a rib of the breast-bone, or Sternon. And this rib is not made of one single bone, but of two side ones, and a third from above, made for a covering to lye upon these; and it is like a scabberd or sheath, and serves for the same use. When the Artery comes to the end of it, it is bent backwards beneath like a Serpent in fashion of the letter S; and by and by it goes forth again beneath the foresaid part of this covering that was placed above it, and ascending to the middle of the channel bones, it leans upon their coupling as on a prop; and being so upheld, it is again bent backwards like a Trumpet, and going under the hollow of the Thorax, before it comes to the lungs, it makes as it were another Larynx, cut athwart, and with a little bone as long as this is broad, and which is covered with a thin membrane; it represents a hollow pipe, or an Organ pipe, in figure and composition, which are open in the neather part of them with the like fissure. Under this Larynx the artery is parted into two channels, each of which in the middle are stretched out wider, and stick forth, and are distributed, going directly to the very small Lungs, that are wholly fastned to the sides behind. This is a wonderfull composition, and it serves for the breathing and voyce.[12]

As Jonstonus notes, the reason this was important was because it allowed the swan to breathe while its long neck was underwater, looking for food.[13]

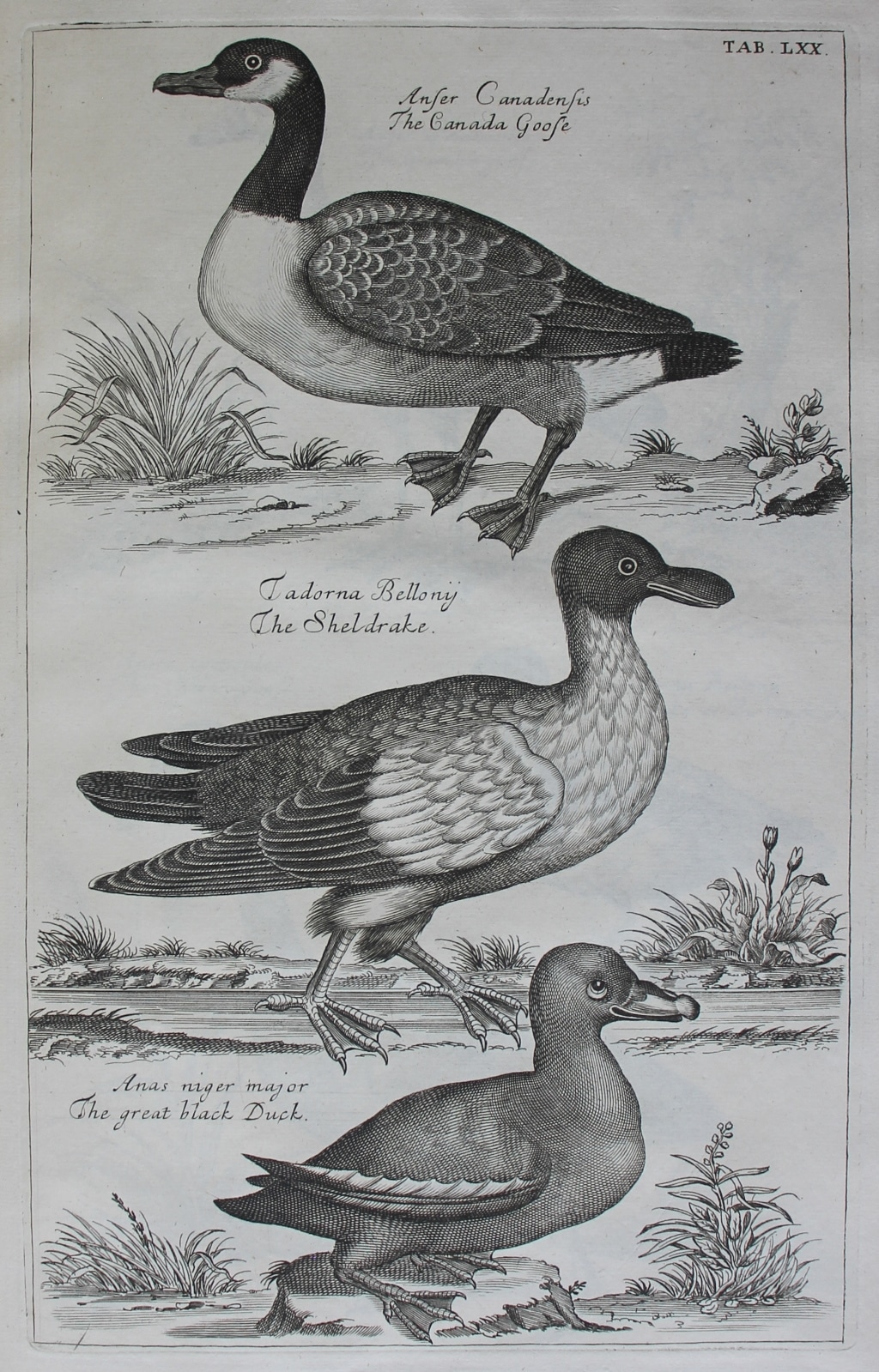

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), Plate 70: The Canada goose, the sheldrake and the great black duck.

Jonstonus had a lot to say about different kinds of geese but his loyalty to his ancestral nation, Scotland, sometimes led him into errors of identification. One example is his whole hearted support for what he calls ‘Soland Geese’, and he argues that ‘amongst all kind of Geese, that is the most wonderful, which in Scotland they call the Soland Goose’.[14] Jonstonus, who was of Scottish ancestry, tells us that he had had the opportunity to see one – or at least smell one, because he declares that when he was in Scotland ‘I smelt of them, and they smelt like Herrings’.[15] This time, channelling the famous Scottish philosopher and historian Hector Boece (1465?–1536), he provided information about nesting and feeding strategies of ‘Soland Geese’:

These so soon as they come at the beginning of the Spring, they do bring so much wood with them to build their nests, that the Inhabitants that dwell there (nor do they repine at it) carry away as much as serves them for fuel a whole year. They feed their young ones with the most choise fish. For if they have caught one, and they see a better swimming at the bottom of the Sea, they let that fall and plunge themselves violently into the waters to catch the other.[16]

Willughby and Ray concurred about the affinity of the ‘Soland Goose’ for Scotland, noting, in particular, that large numbers were to found at the Bass Rock, an island in the Firth of Forth:

In the Bass Island in Scotland, lying in the middle of Edinburgh Frith, and no where else, that I know of, in Britany, a huge number of these Birds doth yearly breed. Each Female lays only one Egg. Upon this Island the Birds, being never shot at or frightned, are so confident as to alight and feed their young ones close by you … They come in the Spring, and go not away again before the Autumn. Whither they go, and where they Winter is to me unknown.[17]

Jonstonus unfortunately does not provide a description of his favourite ‘goose’ but it seems likely that his ‘Soland Goose’ was in fact, not a goose at all, but a Northern Gannet Morus bassanus! Willughby and Ray may have had their doubts about the name and classification of this particular bird because they place their discussion of ‘The Soland Goose. Anser Bassanus’ in their section on ‘Whole-footed Birds with four fore-toes, or four toes all web’d together’, which includes pelicans and cormorants – rather than with other geese.[18]

However, Sir Robert Sibbald (1641–1722), writing in 1684 in his Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684), which Worth also owned, recognised that the ‘Soland Goose’ was, in fact, a gannet, and noted that they were not limited to the Bass Rock but could also be found ‘on Ailsa and other islands of the Hebrides’.[19] This was not the only correction in Sibbald’s work for he included an appendix, hotly disputing the old myth of the origin of Barnacle Geese which he argued had been spread widely by Aldrovandi, who had suggested that they grew on trees in Scotland![20]

Actually Sibbald was being a bit hard on Aldrovandi because various myths concerning Barnacle Geese had been widespread for centuries. As Cabot notes, one of the earliest accounts had been in the controversial Topographica Hibernica of Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis, c. 1146?–c. 1243?):

There are many birds here that are called barnacles, which nature, acting against her own laws, produces in a wonderful way. They are like marsh geese, but smaller. At first they appear as excrescences on fir-logs carried down upon the waters. Then they hang by their beaks from what seems like sea-weed clinging to the log, while their bodies, to allow for their more unimpeded development, are enclosed in shells. And so in the course of time, having put on a stout covering of feathers, they either slip into the water, or take themselves in flight to the freedom of the air. They take their food and nourishment from the juice of wood and water during their mysterious and remarkable generation. I myself have seen many times and with my own eyes more than a thousand of these small bird-like creatures hanging from a single log upon the sea-shore. They were in their shells and already formed. No eggs are laid as is usual as a result of maiting. No bird ever sits upon eggs to hatch and in no corner of the land will you see them breeding or building nests. Accordingly in some parts of Ireland bishops and religious men eat them without sin during a fasting time, regarding them as not being flesh, since they were not born of flesh.[21]

Giraldus Cambrensis must have had extraordinary eyesight indeed if he saw all the things he said he did!

By the end of the sixteenth century the myth was so prevalent that it was even being recorded in herbals. Worth’s herbal collection is extensive and he owned one of the most famous, by the botanist John Gerard (1545–1612), who, in his celebrated Herball describes a ‘Goose Tree’:

There are founde in the north parts of Scotland and the Islands adjacent, called Orchades, certaine trees, whereon do grow certain shells of a white colour tending to russet, wherein are contained little liuing creatures: which shells in time of maturitie do open; and out of them grow those liuing things, which falling into the water do become fowles, whom we call Barnakles; in the North of England, brant Geese; and in Lancashire, tree Geese; but the other that do fall vpon the land perish and come to nothing. Thus much by the writing of others, and also from the mouths of people of those parts, which may very well accord with truth.[22]

Canada Goose; Lough Swilly, Donegal (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Willughby and Ray eschewed such nonsense and were on firmer ground with their description of a Canada Goose for they had had the opportunity to see one in the royal gardens of St James’s Palace in London. In their description they focussed on the colour of the bird’s feathers rather than the bird’s internal structure for clearly they had not had the opportunity to dissect a bird which belonged to the king:

Its length from the point of the Bill to the end of the Tail, or of the Feet is forty two inches. The Bill it self from the angles of the mouth is extended two inches, and is black of colour: The Nosthrils are large. In shape of body it is like to a tame Goose, save that it seems to be a little longer. The Rump is black, but the feathers next above the Tail white: The Back of a dark grey, like the common Gooses. The lower part of the Neck is white, else the Neck black. It hath a kind of white stay or muffler under the Chin, continued on each side below the Eyes to the back of the Head. The Belly is white: The Tail black, as are also the greater quils of the Wings, for the lesser and covert-feathers are of a dark grey, as in the common tame Geese. The Eyes are hazel-coloured, the edges of the Eye-lids in some, I know not whether in all, white: The Feet black, having the hind-toe.[23]

The good news is that, according to BirdWatch Ireland, Canada geese are now thriving in the wild. This image of a Canada Goose Branta canadensis, photographed by Derek O’Reilly at Lough Swilly, Co. Donegal, displays the Canada Goose’s characteristic very long neck and white ‘throat strap’ on its head which, contrasting with the rest of its black head and brown body, makes the bird easily recognisable. While it has some similarities with the Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis, it is much larger.[24]

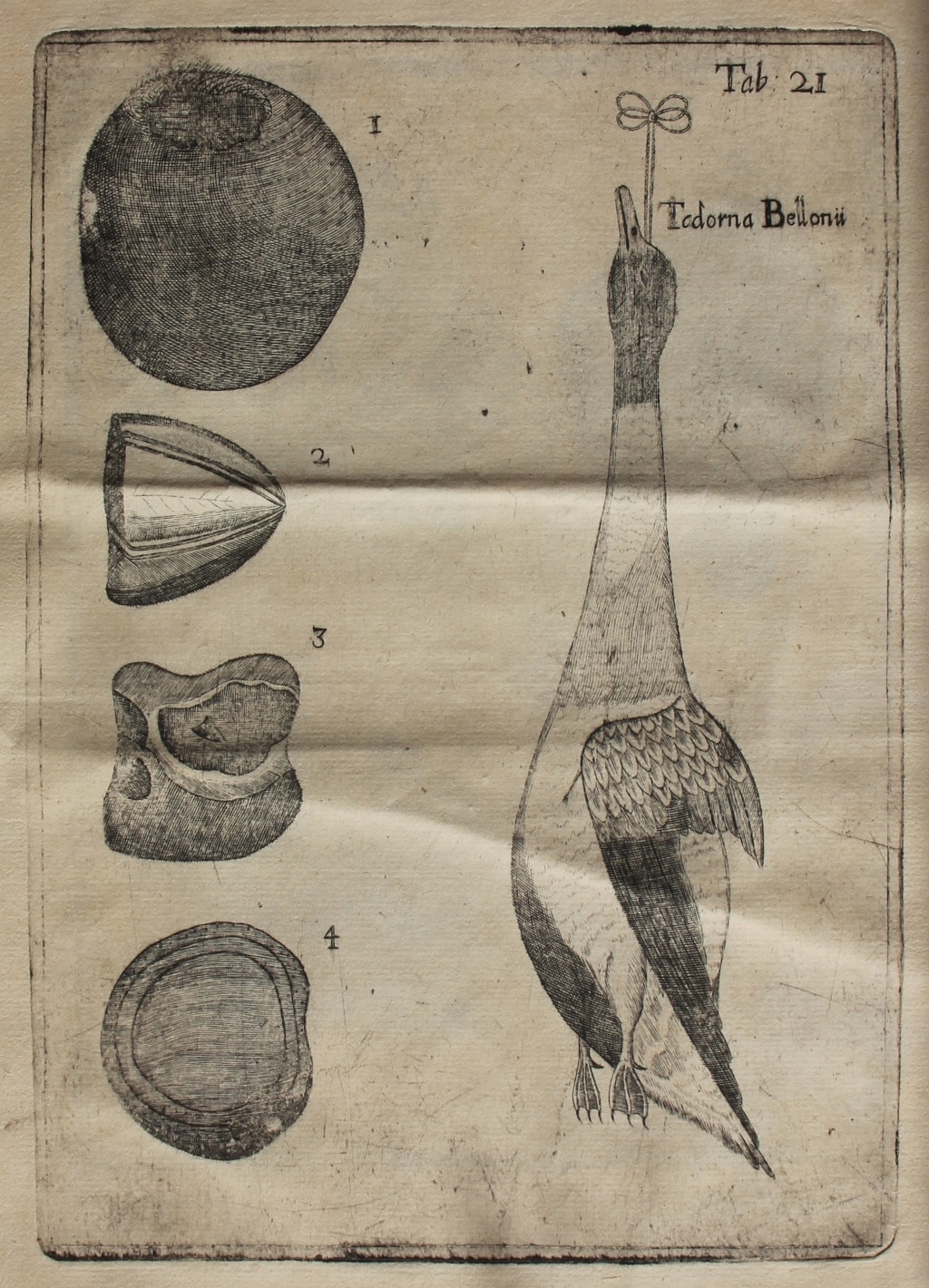

Robert Sibbald, Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684), Tab. 21: ‘Tedorna Bellonii’ – Common Shelduck.

Sibbald’s own section on ducks in his Prodromus concentrated on the large sea-duck the Common Eider Somateria mollissima, and quoted extensively from the Danish scholar Ole Worm’s entry in his Museum Wormianum. Seu Historia rerum rariorum, tam naturalium, quam artificialium, tam domesticarum, quam exoticarum, quae Hafniae Danorum in aedibus authoris servantur. Adornata ab Olao Worm … Variis & accuratis iconibus illustrate (Amsterdam, 1655), which Worth also owned. Worm (1588–1654), could talk more authoritatively about eiders than he had about his much-vaunted ‘penguin’, because Common Eiders were common in Scandinavia.[25] When it came to images, he offered his readers an image of another famous sea-duck, ‘Tedorna Bellonii’, which is the Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna. As Willughby and Ray noted, they were birds with many names for they were ‘called by some, Burrow-Ducks, because they build in Coney-burroughs: By others, Sheldrakes, because they are particoloured: And by others, it should seem, Berganders’ – the latter a name given to them by Aldrovandi.[26]

Shelduck; Bull Island, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Willughby and Ray had seen plenty of them and had noted they could be spotted near ‘the Sea-coasts of Wales and Lancashire’, but they were also ‘frequent about the Eastern shores of England’.[27] This allowed them to provide rather more information than Sibbald had about the dimensions of the bird and the colour of its plumage:

It is of a mean bigness, between a Goose and a Duck. Its Bill is short, broad, something turning upwards, broader at the tip, of a red colour all but the Nosthrils, and the nail or hook at the end, which are black. At the base of the upper Mandible near the Head is an oblong carneous bunch or knob. The Head and upper part of the Neck are of a black, or very dark green, shining like silk, which to one that views it at a distance appears black: The rest of the Neck and region of the Craw milk-white. The upper part of the Breast and the Shoulders are of a very fair orange or bright bay-colour. [The fore-part of the body is encompassed with a broad ring or swath of this colour.] Along the middle of the Belly from the Breast to the Vent runs a broad black line. Behind the Vent under the tail the feathers are of the same orange or bay colour, but paler. The rest of the Breast and Belly, as also the underside of the Wings is white: The middle of the Back white: The long scapular feathers black. All the Wing-feathers, as well quils as coverts, excepting those on the outmost joynt, are white.

Each Wing hath about twenty eight quil-feathers, the ten foremost or outmost whereof are black, as are those of the second row incumbent on them, save their bottoms: Above these toward the ridge of the Wing grow two feathers, white below, having their edges round about black. The next twelve quils, as far as they appear above their covert-feathers, are white on the inside the shaft, on the outside tinctured with a dark shining green. The three next on the inside the shaft are white, on the outside have a black line next the shaft, the remaining part being tinctured with an orange colour. The twenty sixth feather is white, having its outer edge black. The Tail hath twelve feathers, white, and tipt with black, all but the outmost, which are wholly white. The Legs and feet are of a pale red or flesh-colour, the skin being so pellucid that the tract of the veins may easily be discerned through it.[28]

As Cabot rightly remarks, this ‘large, brightly coloured duck is easily mistaken for an exotic goose, bewildering the observer on first encounter’! Luckily we can see them in Ireland – indeed in December 2023 The Irish Bird Blog estimated that there were between 1,000 and 2,000 of them in Dublin Bay alone.[29]

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–1646).

Anon., ‘Dark-bellied brent goose’, Bird Aware Solent.

Anon., ‘Shelduck – the Goosiest Duck’, The Irish Bird Blog, 1 December 2023.

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Besler, Basilius, Rariora Musei Besleriani quae olim Basilius et Michael Rupertus Besleri collegerunt, aeneisque tabulis ad vivum incisa evulgarunt: nunc commentariolo illustrata a Johanne Henrico Lochnero, ut virtuti toy makaritoy exstaret monumentum, denuo luci publicae commisit et laudationem ejus funebrem adjecit maestissimus parens Michael Fridericus Lochnerus (Nuremberg, 1716).

Gessner, Conrad. Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617).

Cabot, David, Wildfowl (London, 2009).

Gerard, John, The herball or Generall historie of plantes (London, 1633).

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

Mullens, W. H., ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, British Birds, 6, no. 2 (1912), 34–57.

Raye, Lee, ‘Robert Sibbald’s Scotia Illustrata (1684): A Faunal Baseline for Britain’, Notes and Records, 72 (2018), 383–405.

Sibbald, Robert, Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684).

Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022).

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Cabot, David, Wildfowl (London, 2009), p. 3.

[2] Ibid., pp 4–5.

[3] Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657), p. 177. This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

[4] Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 151.

[5] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library, pp 355–58.

[6] Ibid., p. 355.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Cabot, Wildfowl, p. 39.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres, p. 151.

[11] Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1640), iii, pp 10–15 (swan skeleton and organs).

[12] Jonstonus, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality, pp 177–8.

[13] Ibid., p. 178.

[14] Ibid., p. 170.

[15] Ibid., p. 171.

[16] Ibid., pp 170–1.

[17] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 329.

[18] Ibid., p. 327.

[19] Mullens, W. H., ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, British Birds, 6, no. 2 (1912), 49.

[20] Sibbald, Robert, Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684), Appendix, pp 36–7.

[21] Cabot, Wildfowl, p. 10.

[22] Gerard, John, The herball or Generall historie of plantes (London, 1633), p. 1588.

[23] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 361.

[24] Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022), p. 20.

[25] Ibid., p. 36.

[26] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 363.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Anon., ‘Shelduck – the Goosiest Duck’, The Irish Bird Blog, 1 December 2023.