Birds of Paradise

Birds of Paradise (Paradisaeidae) were a source of endless fascination in the early modern period and were mentioned in many of the ornithological texts in Edward Worth’s collection. A plume of a bird of paradise might be found in a collection of curiosities such as that of the Danish natural historian Ole Worm (1588–1654), or adorning one of the Magi in Peter Paul Ruben’s Adoration of the Magi, painted between 1609 and 1610 and now in the Prado Museum, Madrid.[1] The colourful feathers of birds of paradise were prized as prestigious head ornaments and it was this use which was initially commented on by Niccolò de’ Conti (1395–1469), a Venetian traveller to the Maluku (Molucca) islands (Indonesian islands of the Malay Archipelago), in the fifteenth century, who was the first European to discuss these strange and beautiful birds.[2]

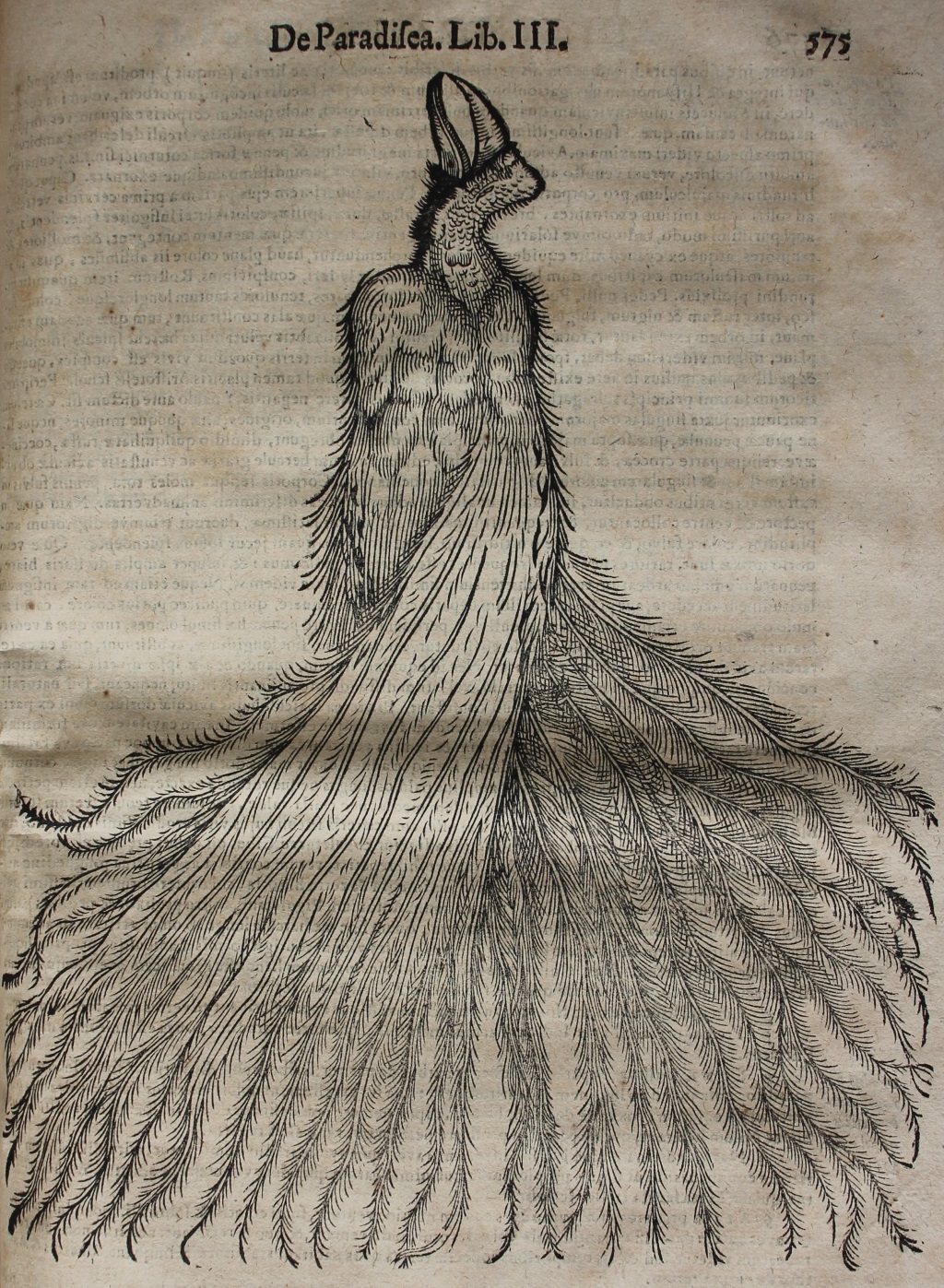

Conrad Gessner, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), Book III, p. 575.

By 1522 specimens of dead birds of paradise had arrived in Europe, along with more detailed accounts of their strange appearance by travellers such as Antonio Pigafetta (c. 1480–c. 1534). Pigafetta, who had sailed with Fernão de Magalhães (Ferdinand Magellan; 1480–1521), offered the first accurate description of the bird, though it was unclear whether he had seen a live one:

These birds are as large as thrushes, and have a small head and a long beak. Their legs are of a palm in length and thin as a reed, and they have no wings, but in their stead long feathers of various colours, like large plumes. Their tail resembles that of the thrush. All the rest of the feathers except the wings are of a tawny colour. They never fly except when there is a wind. The people told us that those birds came from the terrestrial paradise, and they call them bolon diuata, that is the so, ‘birds of God’.[3]

Bird of Paradise, Paradisaea raggiana (P. L. Sclater, 1873), NMNI:1886.28.1.© NMI

To sixteenth-century natural historians such as Conrad Gessner (1516–65), and Pierre Belon (1517–64), they were certainly an oddity and, as Harrison has noted, the latter author, who had seen plumes in the helmets of Turkish janissaries on his travels, later concluded that the beautiful plumes he had seen came from a truly mythical bird, the phoenix:

This feathery creature of which we speak has no legs; but nature, in its effort to supply this defect, has caused it to have two feathers on each side of its tail. These are a foot long and hooked at the end and very hard, so that they hang therewith from trees … Nature gave the Phoenix this peculiarity so that it could avoid the hostility of the beasts who live in the country where it is nurtured. Some are doubtful how the female can cover her eggs. Thus some think that she hatches them on the back of the male and that she covers them on top of him. Others have a different view, thinking that it heaps up twigs, which the sun kindles by its heat, and that from the ash a worm is engendered and from this subsequently the Phoenix is engendered.[4]

One aspect of their appearance was particularly noted in sixteenth-century Europe: they appeared to have no feet. Undoubtedly this was because their feet were cut off in the preparation of the birds for transport, but in Europe their absence gave rise to heated discussions concerning the nature and anatomy of the birds whose appearance was at odds with Aristotle’s well known maxim that all animals (including birds) had legs.[5] As Marciada notes, this ‘legless’ aspect of birds of paradise was generally accepted throughout the sixteenth century.[6] As the above image from Worth’s copy of Gessner’s Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), makes clear, Gessner discounted the testimony of Pigafetta and considered that birds of paradise had no legs. Writing about birds of paradise he argued that:

This account of the bird itself is complete and certain and the most competent of the recent authorities unanimously confirm it, with the sole exception of Antonius Pigafeta, who asserts quite falsely that it is possessed of legs a palm in length, whereas this is, by Hercules, far removed from any truth. I can personally assert that the fact is far different, since on two occasions (for I was not privileged to see it more than twice) I observed it most clearly with my own eyes and hands. This was communicated to me by Guilandinus.[7]

Gessner was not alone in discounting the testimony of Pigafetta, for the Italian natural historian Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), likewise depicted the bird with no legs.

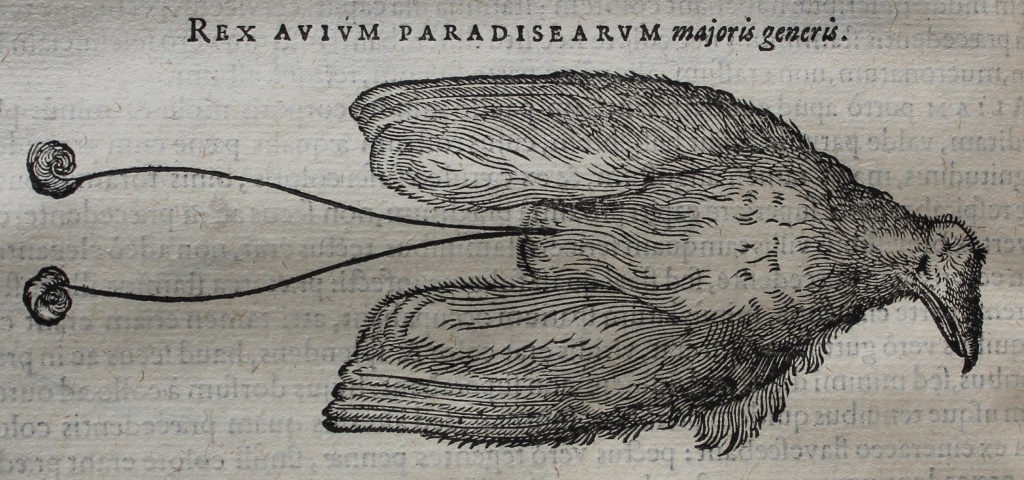

Charles de L’Ecluse (Carolus Clusius), Exoticorum libri decem: quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiæ describuntur: item Petri Bellonii observationes eodem Carolo Clusio interprete (Antwerp, 1605), p. 362: King bird of paradise.

By the beginning of the seventeenth century the view was being challenged and the Flemish physician and botanist Carolus Clusius (1526–1609) led the charge in his Exoticorum libri decem (Antwerp, 1605). As Swadling et al. note, Clusius had access to skins of three species: the Greater, Lesser and King birds of paradise, and unlike Belon, Gessner or Aldrovandi, Clusius, by 1605, was aware that the birds did in fact have legs.[8] Though he included the above image, sent to him by Emanuel Sweerts (1552–1612), of a footless king bird of paradise in his 1605 text, he noted in the appendix to the book that they did indeed have feet.[9] His informant on this point was Jehan de Weely (fl. 1609), who informed Clusius on 13 June 1605 that:

The bird of paradise was in every respect like the vulgar sort, somewhat flat, not of the round kind that they call papauwe, but the other sort with its [snawen?] that they call the feet. It had two feet like a sparrow hawk or harrier, that looked unseemly and ugly; being pressed flat against the belly so that little more than the claws could be seen. The leg was dried and looked ugly too, so that the Indians very sensibly cut off the feet together with the leg, for it is the ugliest part of the bird, and in my opinion they all have similar feet.[10]

Clusius, eager to include this important news ‘hot off the press’, therefore included it in his appendix to his Exoticorum libri decem. It was not until 1609, shortly before his death, that he could verify this fact with his own eyes, when he acquired two birds of paradise.[11] By 1610 another species was brought to Europe: the Twelve-wired bird of paradise.[12] As the century progressed, with the creation of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Comapgnie, VOC), in 1602, more birds of paradise arrived in Holland as it was Dutch merchants who were primarily involved in the trade in birds of paradise.[13]

Francisco Hernández, Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia a Francisco Hernández … primum compilata, dein a Nardo Antonio Reccho in volumen digesta, a Io. Terentio, Io. Fabre, et Fabio, Columna Lynceis notis, & additionibus longe doctissimis illustrata. Cui demum accessere, aliquot ex principis Federici Caesii frontispiciis Theatri naturalis phytosophicae tabulae una cum quamplurimis iconibus ad octingentas, quibus singula contemplanda graphice exhibentur (Rome, 1651), p. 318: Bird of paradise.

The sixteenth-century Spanish physician Francisco Hernández (1517–87), who had been sent by Philip II, King of Spain (1527–98), to New Spain (i.e. Mexico), to study possible medicinal cures and its flora and fauna, also commented on the bird. As Marciada notes, his conclusions were published not only in a 1615 edition in Mexico City and the more famous Roman 1651 edition which Worth owned, and they were also included by the Spanish Jesuit Juan Eusebio Nieremberg (1595–1658), in his Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae … (Antwerp, 1635), which Worth also acquired. Nieremberg combined images based on those of Gessner and Clusius with comments from the manuscript notes of Hernández’s text, then in El Escorial.[14]

Hernández’s dependence on Gessner’s account, with its emphasis on the supposed footless nature of the bird of paradise is clear from his comments on this beautiful bird:

What did those sailors who went to the Moluccas discover but these birds, which do not have the use of their feet, like the oldest species in the world, but these ones are absolutely devoid of feet: instead, in their place they have some feathers, which are orange, hispid, thin, two spans and four inches long, and which grow from the middle of the body like a very thick mane. They use these feathers to hang from trees (when they have stopped flying), since they cannot roost; they also use them to embrace one another when male and female are together, after laying the eggs in a hollow in the male’s back, where they are incubated and protected, hugged in the frontal cavity. Some say that they fly continuously, that they always stay up high, and if by some accident they fall to earth, they are easily captured by children. It is not difficult, given its small body and large feathers, for them to stay airborne and rest on the wing, as if they were roosting in the branches of trees or on the ground.

They are barely bigger than a goldfinch or a tarin, while the length of their plumage is two spans, five inches, no smaller than an eagle’s. This plumage is thin, white tending to reddish, and the feathers grow out of the back and the rest of the body, not from the shoulders or the arms, since they have none. The beak is black, almost two inches long, and somewhat curved. The head and neck are like those of the dove, but that is partly gold and partly royal blue. The neck is royal blue underneath and gold on top. The breast and back are golden with a deeper yellow pattern of semicircles. Toward the tail the feathers, which are short in comparison to the other plumage, is orange tending to gray.

It lives on dew, vapor, and minute animals, or the smallest creatures at the highest altitudes, for nature has ordained that a creature that lives entirely in the air needs no food, or what little can be found there. Yet even though it is perpetually fasting, its little body has plenty of meat and fat on it. The Indians use the dried bird to make headdresses, which they use for the beauty of its plumage, the variety of its colours, and the unusual form and beauty of this bird.[15]

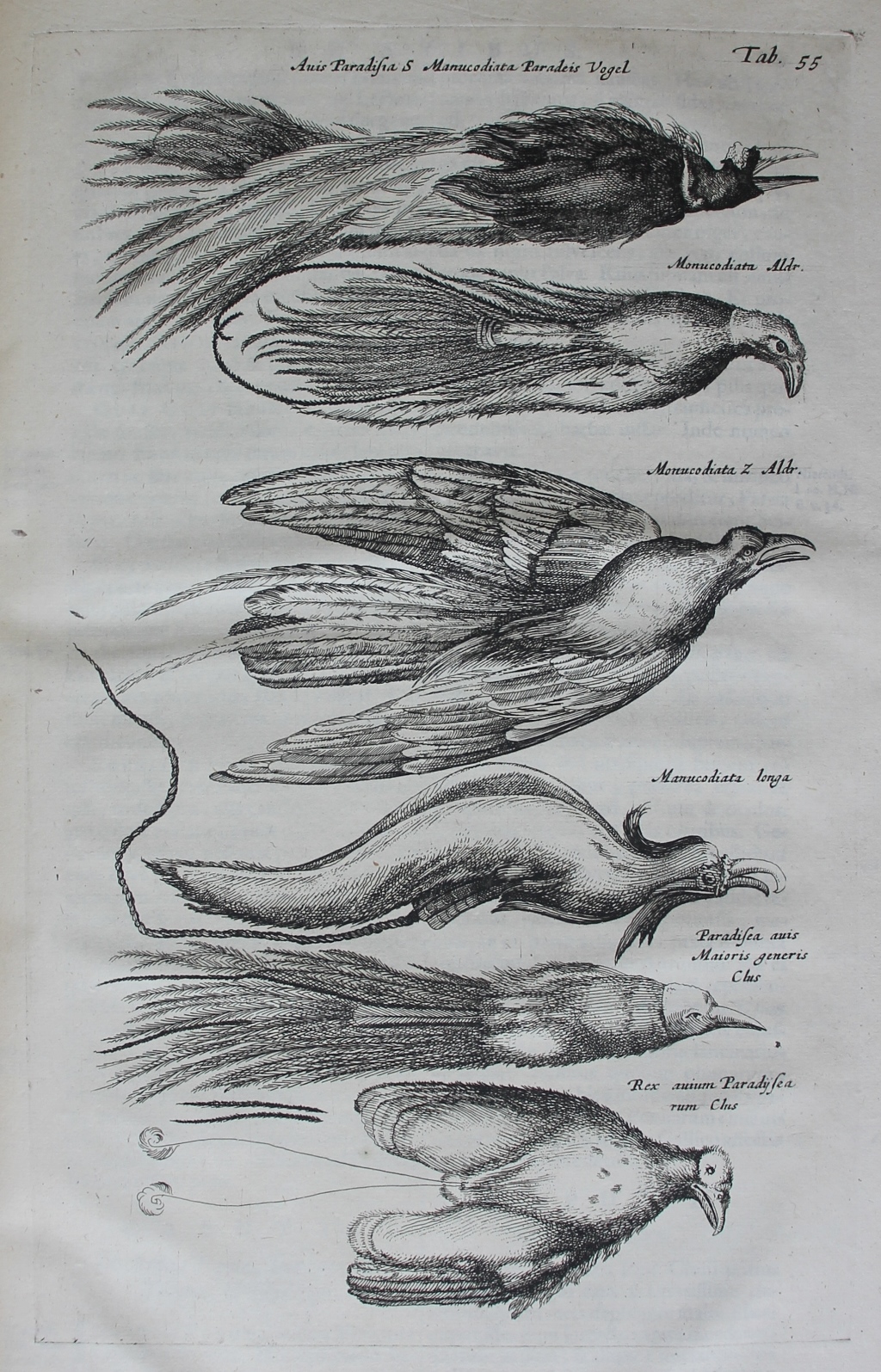

Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), Tab. 55: Birds of paradise.

Jonstonus’s dependence on the ornithological works of Aldrovandi ensured that he too believed that birds of paradise had no legs. In the above image he depicts six skins, including at least two from Aldrovandi and two from Clusius, including a reproduction of Clusius’s above image. His name for the bird ‘Manucodiate Paradeis’ was a latinized version of the Malay name for the bird ‘Manuk dewata’ (God’s birds).[16] But there were in fact many names for these birds: the Portuguese (who had been among the first Europeans to see them in the Maluku Islands), had called them ‘Passaros de Sol’ – ‘birds of the Sun’ (perhaps an allusion to the idea that they lived in the air), while our name, ‘bird of paradise’ was a Dutch construct, for Dutch colonists had called them ‘Avid paradiseus’ (paradise bird).[17]

Red Bird of Paradise, Paradisaea rubra (Daudin, 1800), NMNI:2008.73.246. © NMI

Jonstonus’s work was soon superseded by that of Francis Willughby (1635–72), whose Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676) was owned by Worth (1676–1733). Willughby (and his collaborator John Ray (1627–1705), were trenchant in their demolition of what they termed Aldrovandi’s errors:

That Birds of Paradise want feet is not only a popular persuasion, but a thing not long since believed by learned men and great Naturalists, and among the rest by Aldrovandus himself, deceived by the birds dried or their cases, brought over into Europe out of the East Indies, dismembred, and bereaved of their Feet. Yea, Aldrovandus and others do not stick to charge Antonius Pigafeta, (who gave the first notice of this Bird to the Europaeans) with falshood and lying, because he delivered the contrary. This errour once admitted, the other fictions of idle brains, which seemed thence to follow, did without difficulty obtain belief; viz. that they lived upon the coelestial dew; that they flew perpetually without any intermission, and took no rest but on high in the Air, their Wings being spread; that they were never taken alive, but only when they fell down dead upon the ground: That there is in the back of the Male a certain cavity, in which the Female, whose belly is also hollow, lays her Eggs, and so by the help of both cavities they are sitten upon and hatched. All which things are now sufficiently refuted, and proved to be false and fabulous, both by eye-witnesses, and by the birds themselves brought over entire. I my self (saith Joannes de Laet) have two Birds of Paradise of different kinds, and have seen many others, all which had feet, and those truly for the bulk of their bodies sufficiently great, and very strong Legs. The same is confirmed by Marggravius, Clusius in his Exotics, Wormius in his Museum, page 295. and especially Bontius in the fifth Book and twelfth Chapter of his natural and medic History of the East-Indies, where we have to this purpose; It is so far from being true that these birds of Paradise are nourished by the Air, or want Feet, that with their crooked and very sharp Claws they catch small birds, as Green Linnets, Chaffinches, and the like, and presently tear and devour them like other birds of prey: No less untrue is it, that they are not found but only dead, whereas they sit upon trees, and are shot with Arrows by the Tarnacenses; whence also, and from their swift reciprocal flying, they are by the Indians called Tarnacensian Swallows.[18]

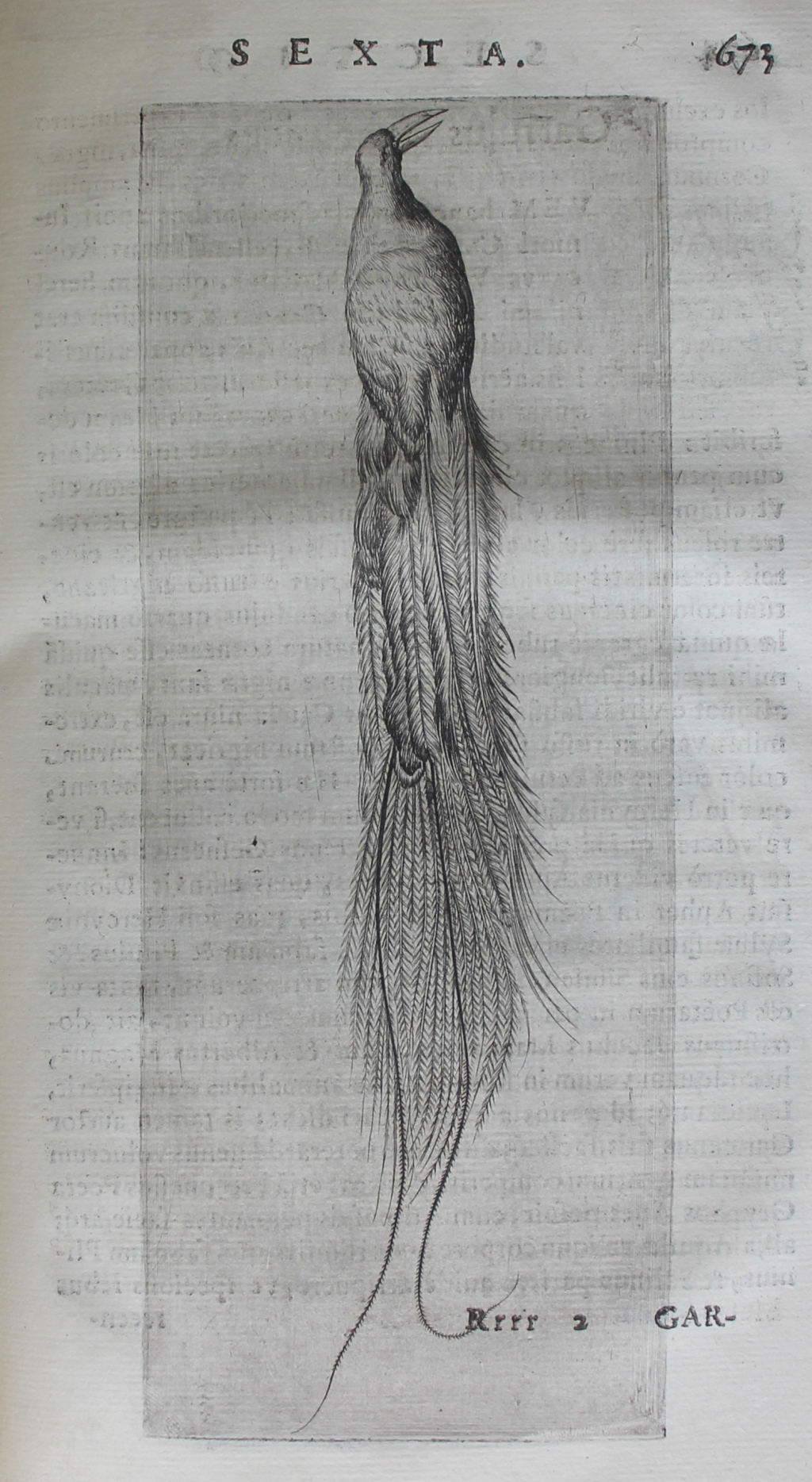

Benedetto Ceruti, Musaeum Franc. CalceolarI iun. veronensis a Benedicto Ceruto medico incaeptum; et ab Andrea Chiocco med. Physico excellentiss. collegii luculenter descriptum & perfectum (Verona, 1622), p. 673: Bird of paradise.

As Mason notes, one of the earliest birds of paradise to find its way into a collection of rarities belonged to Margaret of Austria (1480–1530), Regent of the Netherlands, who in 1523–4 is reported as owning a stuffed bird of paradise – no doubt a gift from her grateful nephew Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–58), on whose behalf she ruled the Netherlands.[19] Birds of paradise were still considered rarities well into the seventeenth century and it is unsurprising to find collectors such as the Danish collector Ole Worm (1588–1654), or the Italian apothecary Francesco Calzeolari (aka Calzolari; 1522–1609), whose cabinet of curiosities was catalogued by Benedetto Ceruti (d. 1620), and brought to press at Verona in 1622, including them in their collections. Fruet draws attention to a gift of a skin of a bird of paradise to Friedrich I, Duke of Württemberg (1557–1608), from Count Philipp von Hohenlohe (1550–1606), and both skins and feathers were clearly considered high-status gifts.[20]

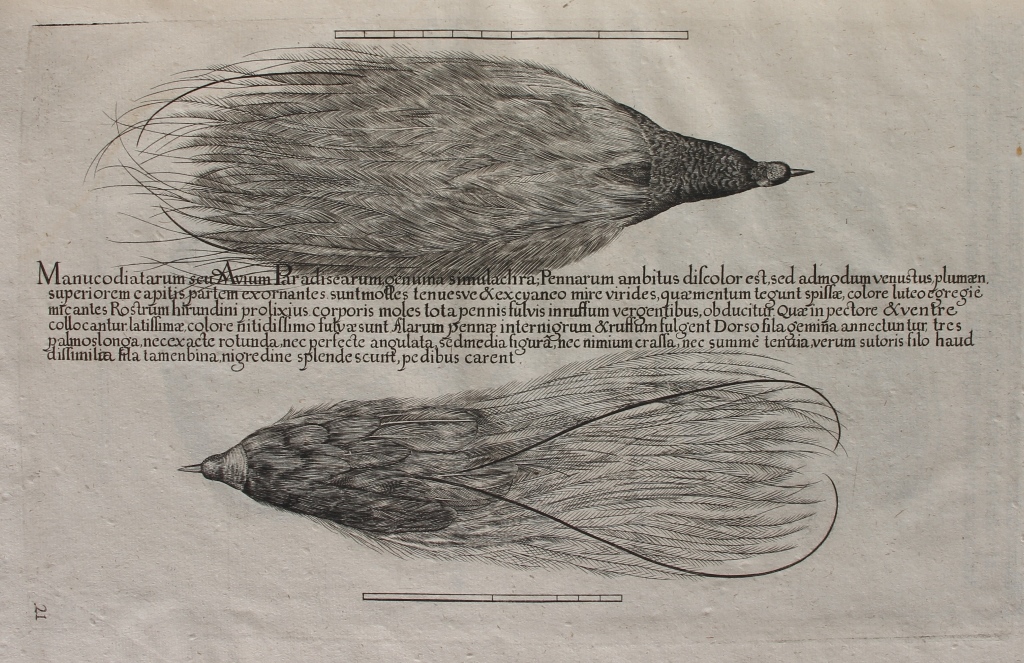

Michael Rupert Besler, Gazophylacium rerum naturalium: e regno vegetabili, animali & minerali depromptarum, nunquam hactenus in lucem editarum, cum figuris aeneis ad vivum incisis, opera Michaelis Ruperti Besleri (Leipzig and Frankfurt, 1716), plate 21: Bird of paradise.

Thirty-eight of the forty-two species of birds of paradise may be found in New Guinea and its islands, and the plumes of these birds have long been prized possessions, both within the islands and beyond.[21] The above image from Worth’s copy of Michael Rupert Besler’s Gazophylacium rerum naturalium: e regno vegetabili, animali & minerali depromptarum, nunquam hactenus in lucem editarum, cum figuris aeneis ad vivum incisis, opera Michaelis Ruperti Besleri (Leipzig and Frankfurt, 1716), gives us some indication of the richness of the plumes and their attraction. Beauty was not their only important characteristic: the islanders of the Maluku Islands were said to consider them to be important aids in battle for wearing plumes was said to render the wearer unbeatable.[22] This had been commented on as early as 5 October 1522, when some of the first plumes were sent as a gift to Charles V, whose secretary Maximilianus Transylvanus (1490–c. 1538), noted this aspect of the famous bird:

They hold these manucodiatas to be celestial, and even when they are dead they never corrupt or smell. Their plumage is of diverse and very beautiful colours, they are the size of turtle-doves, and have a very long tail, and if one of their feathers is plucked, another grows, even when they are dead. The kings take them into battle, and believe that if they have them with them they are safe and invincible in battle.[23]

The seventeenth-century German physician and apothecary Michael Rupert Besler (1607–71), was not concerned with such beliefs about the bird. A nephew of Basil Besler (1561–1629), another apothecary based in Nuremberg, who had been responsible for the massive Hortus Eystettensis (Nuremberg?, 1640), which was likewise owned by Worth, Besler junior aimed instead to provide for his readers ‘genuine images’ of this beautiful bird.

Bird of Paradise, Paradisaea raggiana (P. L. Sclater, 1873), NMNI:1886.28.1. © NMI

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Attenborough, David, and Erroll Fuller, Drawn from Paradise : the discovery, art and natural history of the Birds of Paradise (London, 2012).

Fruet, Arlette, ‘L’idée d’un oiseau : l’oiseaux de paradis ou la fabrication d’une merveille (XVIe et XVIIe siècles)’, in Garrod, Raphaële, and Paul J. Smith (eds), Natural History in Early Modern France: The poetics of an epistemic genre (Leiden, 2018), 70–87.

Harrison, Thomas P., ‘Bird of Paradise: Phoenix Redivivus’, Isis, 51, no. 2 (1960), 173–80.

Kleiter, Christine, ‘Birds, Colour, and Feet: A “Naïf Portrait” of the Brazilian Tanager in Pierre Belon’s L’Histoire de la Nature des Oyseaux’, Journal of the LUCAS Graduate Conference, 8 (2020), 6–29.

Marcaida, José Ramón, ‘Rubens and the bird of paradise. Painting natural knowledge in the early seventeenth century’, Renaissance Studies, 28, no. 1 (2014), 112–127.

Marcaida, José Ramón, ‘Bird of Paradise’, in Thurner, Mark, and Juan Pimentel (eds), New World Objects of Knowledge: A Cabinet of Curiosities (London, 2021), pp 155–57.

Mason, Peter, Before Disenchantment: Images of exotic animals and plants in the early modern world (London, 2009).

Nieremberg, Juan Eusebio, Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae, libris XVI distincta … Accedunt de miris & miraculosis naturis in Europa libri duo; item de iisdem in terra Hebraeis promissa liber unus (Antwerp, 1635).

Norton, Marcy, ‘The Quetzal takes flight: microhistory, Mesoamerican knowledge, and early modern natural history’, in Arredondo, Jaime Marroquín, and Ralph Bauer (eds), Translating Nature: Cross-Cultural Histories of Early Modern Science (Pennsylvania, 2019), pp 119–47.

Swadling, Pamela, with contributions from Roy Wagner and Billai Laba, Plumes from Paradise: Trade Cycles in Outer Southeast Asia and Their Impact on New Guinea and Nearby Islands Until 1920 (Sydney, 2019).

Swan, Claudia, ‘Exotica on the Move: Birds of Paradise in Early Modern Holland’, Art History, 38, no. 4 (2015), 620–35.

Varey, Simon, Rafael Chabrán and Dora B. Weiner (eds), Searching for the secrets of nature: The life and works of Dr. Francisco Hernández (Stanford, 2000).

Varey, Simon (ed.), The Mexican Treasury: The writings of Dr. Francisco Hernández (Stanford, 2000).

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Worth owned a copy of Ole Worm’s Museum Wormianum. Seu Historia rerum rariorum, tam naturalium, quam artificialium, tam domesticarum, quam exoticarum, quae Hafniae Danorum in aedibus authoris servantur (Amsterdam, 1655). On Rubens see Marcaida, José Ramón, ‘Rubens and the bird of paradise. Painting natural knowledge in the early seventeenth century’, Renaissance Studies, 28, no. 1 (2014), 112–127.

[2] De’ Conti’s comments on birds of paradise were later printed in India Recognita (Milan, 1492). This work was not collected by Worth.

[3] Harrison, Thomas P., ‘Bird of Paradise: Phoenix Redivivus’, Isis, 51, no. 2 (1960), 174.

[4] Translated in ibid., 176.

[5] Marcaida, ‘Rubens and the bird of paradise’, 116.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Translated in Harrison, ‘Bird of Paradise: Phoenix Redivivus’, 177.

[8] Swadling, Pamela, with contributions from Roy Wagner, and Billai Laba, Plumes from Paradise: Trade Cycles in Outer Southeast Asia and Their Impact on New Guinea and Nearby Islands Until 1920 (Sydney, 2019), p. 65.

[9] Mason, Peter, Before Disenchantment: Images of exotic animals and plants in the early modern world (London, 2009), p. 134.

[10] Ibid., p. 136.

[11] Swan, Claudia, ‘Exotica on the Move: Birds of Paradise in Early Modern Holland’, Art History, 38, no. 4 (2015), 630.

[12] Swadling, et al., Plumes from Paradise, p. 65.

[13] Swan, ‘Exotica on the Move’, 621, 623.

[14] Nieremberg, Juan Eusebio, Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae, libris XVI distincta … Accedunt de miris & miraculosis naturis in Europa libri duo; item de iisdem in terra Hebraeis promissa liber unus (Antwerp, 1635), p. 211.

[15] Varey, Simon (ed.), The Mexican Treasury: The writings of Dr. Francisco Hernández (Stanford, 2000), pp 216–17.

[16] Harrison, ‘Bird of Paradise: Phoenix Redivivus’, 174.

[17] Swadling, et al., Plumes from Paradise, p. 64.

[18] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 90. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[19] Mason, Before Disenchantment, p. 135.

[20] Fruet, Arlette, ‘L’idée d’un oiseau : l’oiseaux de paradis ou la fabrication d’une merveille (XVIe et XVIIe siècles)’, in Garrod, Raphaële, and Paul J. Smith (eds), Natural History in Early Modern France: The poetics of an epistemic genre (Leiden, 2018), p. 25.

[21] Swadling, et al., Plumes from Paradise, p. 49.

[22] Ibid., p. 62.

[23] Mason, Before Disenchantment, p. 135.