Birds of Prey

‘The Characteristic notes of Rapacious Birds in general are these: To have a great head; a short neck; hooked, strong and sharp-pointed Beak and Talons, fitted for ravine and tearing of flesh’.[1]

So says Francis Willughby (1635–72), in his seminal work Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), which his collaborator, John Ray (1627–1705), translated into English in 1678. Willughby began his descriptions of birds with eagles, the king of the birds, and carried on to discuss other ‘Rapacious Diurnal’ birds of prey such as falcons, hawks, buzzards and vultures, before moving on to examine ‘Rapacious Nocturnal’ birds of prey, such as owls. In this approach Willughby was not alone, for early modern ornithologists were fascinated by birds of prey of all kinds.

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 95: Gyrfalcon with falconer.

Some birds of prey received more attention than others and certainly gyrfalcons were considered to be status symbols in the early modern period. The French natural historian Pierre Belon (1517–64), writing in 1555, noted the rarity of this bird which was believed to come from the north and which was not native to France.[2] Falconers admired gyrfalcons for their hunting prowess, rulers coveted them as high-status gifts, and even famous historians such as Jacques Auguste de Thou (1553–1617), lauded this magnificent bird as ‘the finest, handsomest bird among the raptors, and stands out by her character and strength’.[3] Belon suggests that authors such as Pliny the Elder (23/4–79), had written about it.[4] Gyrfalcons had certainly featured in the famous treatise De arte venandi cum avibus of Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1194–1250), and some of his remarks were reused by contemporaries of Belon such as Conrad Gessner (1516–65), and Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), when writing about the bird in the sixteenth century.[5] Many commentators referred to gyrfalcons as ‘hawks of the fist’ and in his image Belon was perhaps trying to draw attention to the fact that gyrfalcons, like goshawks and sparrowhawks, tend to fly from the fist of the falconer.[6]

Gyrfalcon, Falco rusticolus (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1884.230.1. © NMI

Early modern commentators were fascinated by the etymology of the bird and where it came from. Most, like Belon, associated it with the far-north and it is true that nests of gyrfalcons dating between 6,000 and 6,500 years have been located in Greenland.[7] Travel accounts linked the bird to Russia and certainly the English poet and translator George Turberville (b. 1543/4, d. in or after 1597), appears to have seen a gyrfalcon in Moscow in 1568 during his sojourn there as part of an English embassy to the court of Tsar Ivan the Terrible (1530–84), for he records that ‘At my being in Moscovia, I sawe sundrie Gerfalcons, verie fayre and huge hawkes, and of all other kyndes of hawkes, that onely bryde is there had in accompte and regarde, and is of greater price than any other’.[8] As De Smet has argued, Russia was certainly one source of gyrfalcons coming to western Europe but Scandinavian countries such as Denmark also provided these precious birds.[9] And the birds were certainly precious for Belon notes that they sold for something between twenty and twenty-five écus in France.[10] The Italian natural historian Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605) says that while the birds were also costly in Italy, the French were particularly addicted to gyrfalcons and that consequently they sold there ‘at any price’.[11]

Aldrovandi, with his links to courts, was well-placed to examine expensive birds such as gyrfalcons and in his Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I], which Worth owned in a Bologna edition of 1637–46, he included an image of a Norwegian gyrfalcon which belonged to Alfonso II d’Este (1533–97), Duke of Ferrara.[12] Falconry was big business at early modern courts – Macgregor suggests that James I (1566–1625), King of England, Scotland and Ireland, employed 24 falconers in 1624, and both he and his son, Charles I (1600–49), were keen on building up stocks of birds on royal estates.[13]

Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), plate XIII: falcons.

Gyrfalcons are the largest of the falcon species and their size and strength gives them advantages over other birds of prey.[14] Jonstonus (1603–75), included information about them in his chapter on falcons in Worth’s copy of Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657):

A Faulcon is so strong, that when he strikes a bird, he will cut him in two, from head to tail … The Gyrfaulcons are of divers kinds; They are some white found in Moscovy, Norway, Ireland. They are bold: If one of them be let fly at five Cranes, he will follow them all till he have killed them. The food of it reserved in its Cave, it will take in order. She never wets her self with water, but onely with sand. She loves the cold so well, that she will alwayes delight to stand upon ice, or upon a cold stone: sometimes untaught she is sold for 50 Nobles. There is a Faulcon called Rueus, because the spots, that are white in the rest, are red and black in this kind; yet they seem not to be so, but when she stretcheth forth her wings. The cause of this rednesse is a feeble colour infused into the superficies of the body, and inflaming the smoaky moysture, which is put forth to breed the feathers.[15]

Jonstonus’s reference to Ireland is probably due to his dependence on Aldrovandi (and Gessner) who mistakenly included an Irish link due a mis-translation of ‘Hirlandia’, which was, according to Belisario Acquaviva (1464–1528), the homeplace of a gyrfalcon sent to Emperor Maximilian I (1486–1519). As De Smet notes, in his De venatione et de aucupio de re militari et singulari certamine (Naples, 1519), Belisario Acquavica was not talking about Ireland but Iceland![16]

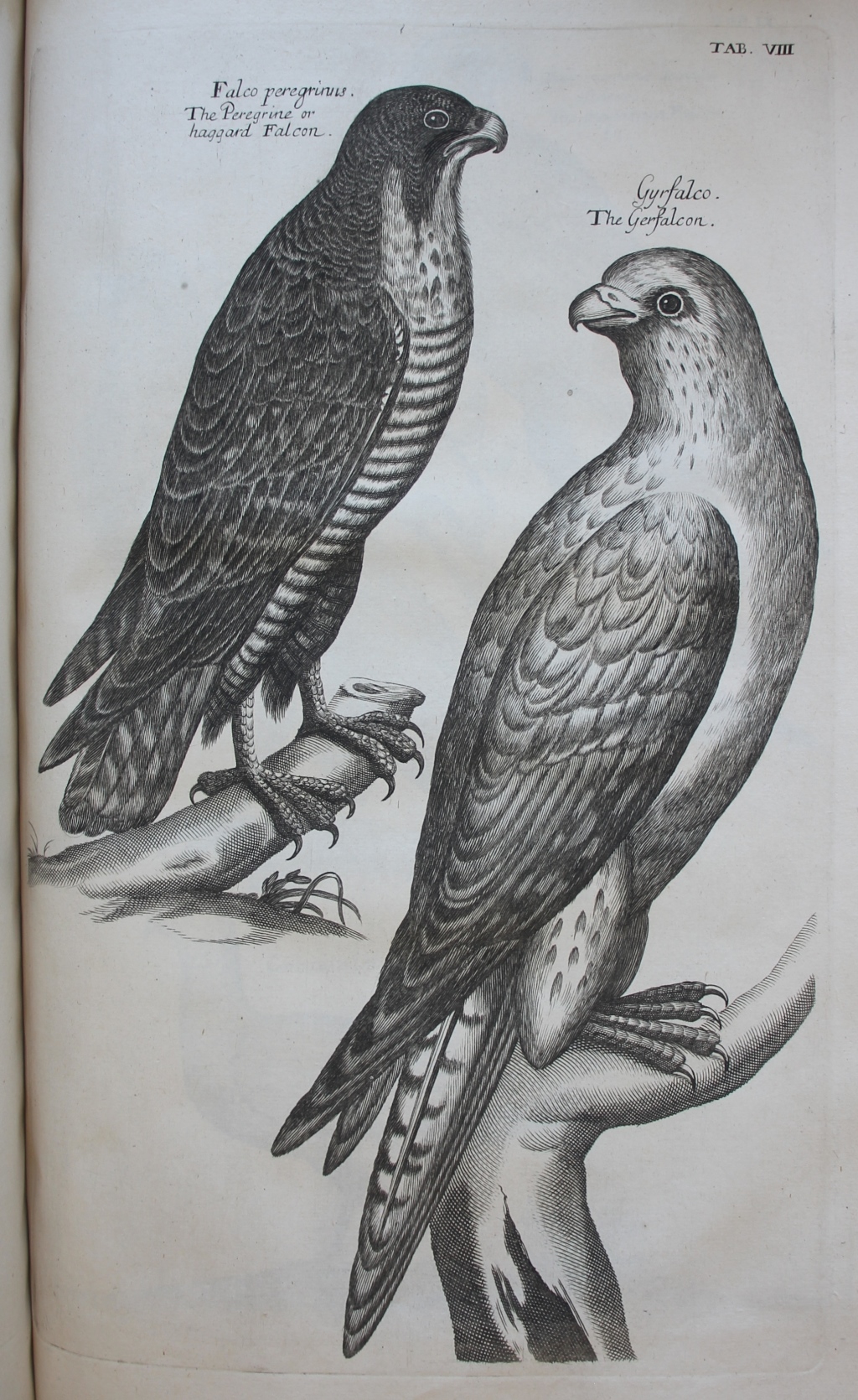

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate VIII: Peregrine falcon and gyrfalcon.

Willughby (and Ray) were also interested in gyrfalcons and included this handsome image of a gyrfalcon (on the right) and a peregrine falcon (on the left). Willughby considered gyrfalcons ‘a couragious, fierce, and very bold Bird, catching all sorts of Fowl how great soever, and is terrible to other Falcons and Goshawks. Its chief Game are Cranes and Herons’, but they had not had the opportunity to see one themselves, and relied instead on earlier sources such as Frederick II’s De arte venandi cum avibus, and Aldrovandi’s Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I], who had greater opportunities to see gyrfalcons up-close. Aldrovandi provided the following detailed description:

Of that which Aldrovandus described this was the shape: The Crown was plain and depressed, of an ash-colour. The Beak thick, strong, short, blue; bowed downward with a mean-sized hook, but very sharp, strong, and blewish. The Pupil of the Eyes very black, the Iris or Circle encompassing the Pupil blue. The Back, Wings, Belly, and Train were white: But the feathers of the Back and Wings were almost every one marked with a black spot, imitating in some measure the figure of a heart, like the Eyes in a Peacocks tail. The flag-feathers of the Wings near their tips beautified with a bigger and longer black mark, which is yet enclosed with a white margin or border. The Wings very long, so that they wanted but little of reaching to the end of the Tail. The Throat, Breast, and Belly purely white, without any spots at all. The Tail not very long, yea, in respect of its body and those of other Falcons rather short, marked with transverse black bars. The Legs and Feet of a delayed blue. The Legs thick and strong. The Toes long, strong, broad-spread, covered all over with a continued Series of board-like Scales.[17]

Peregrine, Falco peregrinus Tunstall, 1771, NMINH:1900.121.1. © NMI

Willughby and Ray were likewise dependent on what Aldrovandi had said concerning peregrine falcons for neither had had a chance to see one.[18] They noted that Aldrovandi had spotted one in mountains near Bologna and he certainly provided an authoritative description of the bird:

From the top of the Head to the end of the Tail it was seventeen Inches long. The Crown of the head flat and compressed: The Beak an Inch thick, of a lovely sky-colour, bending downward with a sharp hook, short, strong, joyned to the head with a yellow Membrane of a deep colour, which compasses the Nosthrils; the Eye blue, the edges of the Eye-lids round yellow. The Head, Neck, Back, Wings of a dark brown, almost black, sprinkled with black spots in almost every feather, the great feathers being crossed with transverse ones. The Throat was of a yellowish white, the lower part thereof being stained with black spots, as it were drops drawn out in length from the corners of the Mouth on each side a black line was drawn downwards almost to the middle of the Throat or Gullet. The Breast, Belly, and Thighs white, crossed with broad, transverse, black lines. The tips of the Wings, when closed, reached almost to the end of the Train. The Train less dusky, marked also with black cross bars. The Legs and Feet yellow; the Thighs long, the Shanks short; the Toes slender, long, covered with scales, as are also the Legs; the Talons black, and very sharp.[19]

Willughby and Ray clearly considered peregrine falcons as important inclusions in their work, declaring that they were including Aldrovandi’s description ‘lest the Ornithology we set out should be defective and imperfect in this particular’, and placing it first in their discussion of falcons.[20] They were, however, ‘not a little troubled’ that they could not provide personal testimony concerning peregrine falcons.[21]

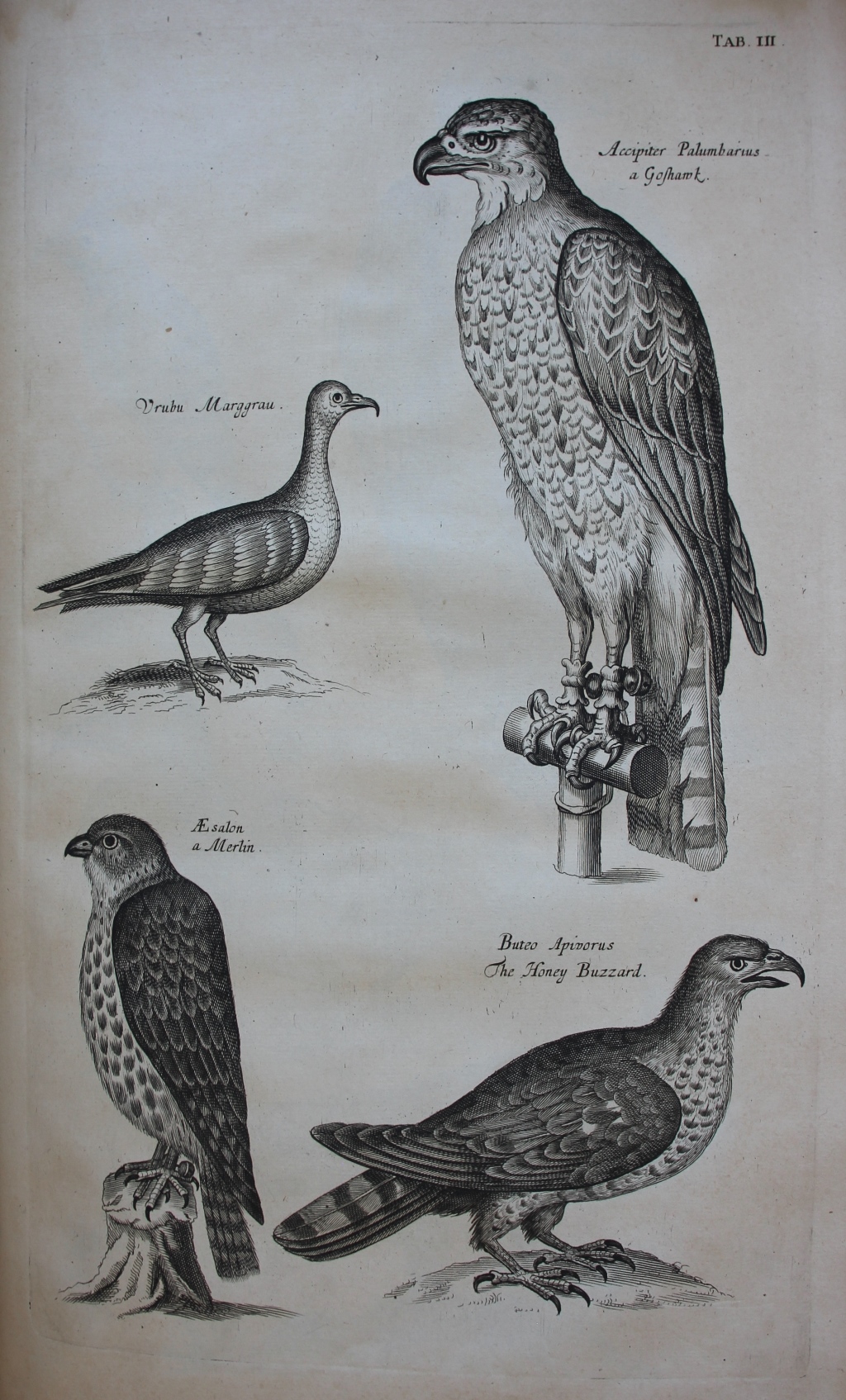

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate III; including a goshawk, a merlin and a honey buzzard.

In other areas Willughby and Ray were in the happy position of being able to provide cutting edge research: Birkhead notes that Willughby was the first ornithologist to make a distinction between the Honey Buzzard (Pernis apivorus) and the Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo). Willughby provided his readers with a detailed description of a Honey Buzzard:

For bigness it equals or exceeds the common Buzzard, is also like it in figure or shape of body, unless perchance it be somewhat longer. It weighed thirty one ounces. The length from Bill-point to Tail-end was twenty three Inches, to the points of the Talons not more than nineteen. Its breadth or the distance between the ends of the Wings spread fifty two Inches. Its beak from the tip to the Angles of the mouth was an inch and half long, black, and very hooked, bunching out between the nosthrils and the head: The Basis of the upper Chap covered with a thick, rugged, black skin beyond the Nosthrils, which are not exactly round, but long and bending. The mouth, when gaping, very wide and yellow. The Angle of the lower Chap, as in other Hawks, semicircular. The Irides of the Eyes of a lovely bright yellow or Saffron colour.

The head is ash-coloured: The Crown flat, broad, narrow toward the Beak. The bottoms of the Plumage in the head and back white, which is worthy the noting, because it is common with this to many other Hawks. The back is of a ferrugineous colour [or rather a Mouse-dun.] The tips of the flag-feathers, as also those of the second and third rows in the wings white. The Wings when closed reach not to the end of the tail. The number of flags in each Wing twenty four. The Tail consists of twelve feathers, near a foot long, variegated with transverse obscure and lucid, or blackish and whitish spaces, rings, or bars. The very tips of the feathers are white, below the white is a cross black line; under that a broad dun or ash-coloured space or bed (the like whereto also crosses the wings, which differ not much from the tail in colour.)

As for the lower side of the body, the feathers under the chin and tail are white; the breast and belly also white, spotted with black spots, drawn downward from the head toward the tail. The Legs are feathered down somewhat below the knee, short, strong, yellow, as are also the feet. The Talons, long, strong, sharp, and black. The Guts shorter than in the former: The Appendices thick and short. In the stomach and guts of that we dissected we found a huge number of green Caterpillars of that sort called Geometrae, many also of the common green Caterpillars and others. It builds its Nest of small twigs, laying upon them wool, and upon the wool its Eggs. We saw one that made use of an old Kites Nest to breed in, and that fed its Young with the Nymphae of Wasps: For in the Nest we found the Combs of Wasps Nests, and in the stomachs of the Young the limbs and fragments of Wasp-Maggots. There were in the Nest only two young ones, covered with a white Down, spotted with black. Their Feet were of a pale yellow, their Bills between the Nosthrils and the head white. Their Craws large, in which were Lizards, Frogs, &c. In the Crop of one of them we found two Lizards entire, with their heads lying towards the birds mouth, as if they sought to creep out. This Bird runs very swiftly like a Hen. The Female as in the rest of the Rapacious kind is in all dimensions greater than the Male.[22]

Willughby was at pains to make it clear that this was not a Common Buzzard: ‘It differs from the common Buzzard, 1. In having a longer tail. 2. An ash-coloured. 3. The Irides of the Eyes yellow. 4. Thicker and shorter feet. 5. In the broad transverse dun beds or stroaks in the wings and tail; which are about three inches broad’.[23] As Birkhead et al. note, the European Honey Buzzard’s liking for feeding on the nests of wasps indirectly gave it its name for the nests looked at times like honey combs.[24]

Top left: Black Vulture, Aegypius monachus (Linnaeus, 1766), NMINH:2003.52.139. © NMI; top right: Goshawk, Astur gentilis (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1919.101.1. © NMI; bottom right: Honey Buzzard, Pernis apivorus (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1881.570.1. © NMI; bottom left: Merlin, Falco columbarius (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1878.16.1. © NMI

As Birkhead et al. emphasise, Willughby was the first to distinguish between the two for though Belon had alluded to a bird he called by various names (‘Boudree’, ‘Goiran’ and ‘Bondree’), his description of it was less than clear:

When the bird is flying, one immediately recognises this species, because it does not have a forked tail, and also because it often flaps its wings, just like the buzzard and not like the kite or the marsh harrier. It is otherwise called Boudree, And to get to the truth of the matter, and to be sure [of its identity], it is very important to pay attention to its identifying marks, Thus, when one turn’s the wings upside down, one finds that the tips of the first five [primary] feathers are black but the rest of the feather is white, except for the outside. In flight it appears white from below because of the white mark on both wings, but, when perched, the bird seems ash-black … Its legs are short, and not completely round, being only smooth in front and back, and scaly on the sides, which are yellow. Its bill is short, black at the tip, and hooked, but yellow around the nostrils, and at the borders of its bill. This is the one that Aristotle, in the 36th chapter of his 9th book on the nature of animals, has named Rubetarius Accipiter … We would not have inserted it in this place [of the book], but for the doubt that the Boudree is in fact a Buzzard’.[25]

Belon appears, in this passage, to understand that there are two species of Buzzard but at the same time includes elements which relate to the Common Buzzard – its yellow cere – and his previous suggestion that the birds were caught ‘especially in wintertime’, also points, as Birkhead et al. point out, to the Common Buzzard and not the European Honey-Buzzard.[26]

Merlin; Donabate, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

If gyrfalcons were among the largest birds of prey, merlins were among the smallest. Belon, Willughby and Ray all noted the relative size of the bird but also that its smaller size did not impact on its hunting abilities. As Willughby noted ‘The Merlin, though the least of Hawks, yet for spirit and mettle (as Albertus truly writes) gives place to none. It strikes Partridge on the Neck, with a fatal stroke, killing them in an instant. No Hawk kills her prey so soon’.[27]

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Birkhead, T. R., et al., ‘Willughby’s Buzzard: names and misnomers of the European Honey-Buzzard (Pernis apivorus)’, Archives of Natural History, 45, no. 1 (2018), 80–91.

De Smet, Ingrid A. R., ‘Princess of the North: perceptions of the gyrfalcon in 16th-century western Europe’, in Gersmann, Karl-Heinz, and Oliver Grimm (eds), Raptor and human – falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale (Schleswig, 2018), pp 1543–69.

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

MacGregor, Arthur, ‘Animals and the early Stuarts: hunting and hawking at the court of James I and Charles I’, Archives of Natural History, 16, no. 3 (1989), 305–18.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 55. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[2] Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), pp 95–6.

[3] De Smet, Ingrid A. R., ‘Princess of the North: perceptions of the gyrfalcon in 16th-century western Europe’, in Gersmann, Karl-Heinz, and Oliver Grimm (eds), Raptor and human – falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale (Schleswig, 2018), p. 1547.

[4] Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, p. 95.

[5] De Smet, ‘Princess of the North: perceptions of the gyrfalcon in 16th-century western Europe’, p. 1545.

[6] Ibid., pp 1555–6.

[7] Ibid., p. 1548.

[8] Ibid., p. 1551.

[9] Ibid., pp 1551–2.

[10] Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, p. 96.

[11] Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1646), i, p. 477.

[12] Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I], pp 472–3, 475; De Smet, ‘Princess of the North: perceptions of the gyrfalcon in 16th-century western Europe’, p. 1554.

[13] MacGregor, Arthur, ‘Animals and the early Stuarts: hunting and hawking at the court of James I and Charles I’, Archives of Natural History, 16, no. 3 (1989), 312.

[14] De Smet, ‘Princess of the North: perceptions of the gyrfalcon in 16th-century western Europe’, p. 1544.

[15] Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657), p. 179. This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

[16] De Smet. ‘Princess of the North: perceptions of the gyrfalcon in 16th-century western Europe’, p. 1548.

[17] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 78.

[18] Ibid., p. 76.

[19] Ibid., p. 77.

[20] Ibid., p. 76.

[21] Ibid., p. 76.

[22] Ibid., p. 72.

[23] Ibid., p. 72.

[24] Birkhead, T. R., et al., ‘Willughby’s Buzzard: names and misnomers of the European Honey-Buzzard (Pernis apivorus)’, Archives of Natural History, 45, no. 1 (2018), 84.

[25] Translation from Birkhead, T. R. et al., ‘Willughby’s Buzzard: names and misnomers of the European Honey-Buzzard (Pernis apivorus)’, 90–1.

[26] Ibid., 90, 82.

[27] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 85.