Willughby on Owls

The brilliant English ornithologists Francis Willughby (1635–72), and John Ray (1627–1705), were clearly fascinated by owls, nocturnal birds of prey, which they had ample opportunity to study, both in England and on their continental travels. They thus included detailed descriptions and beautiful images of them in their section on ‘Rapacious nocturnal birds’.

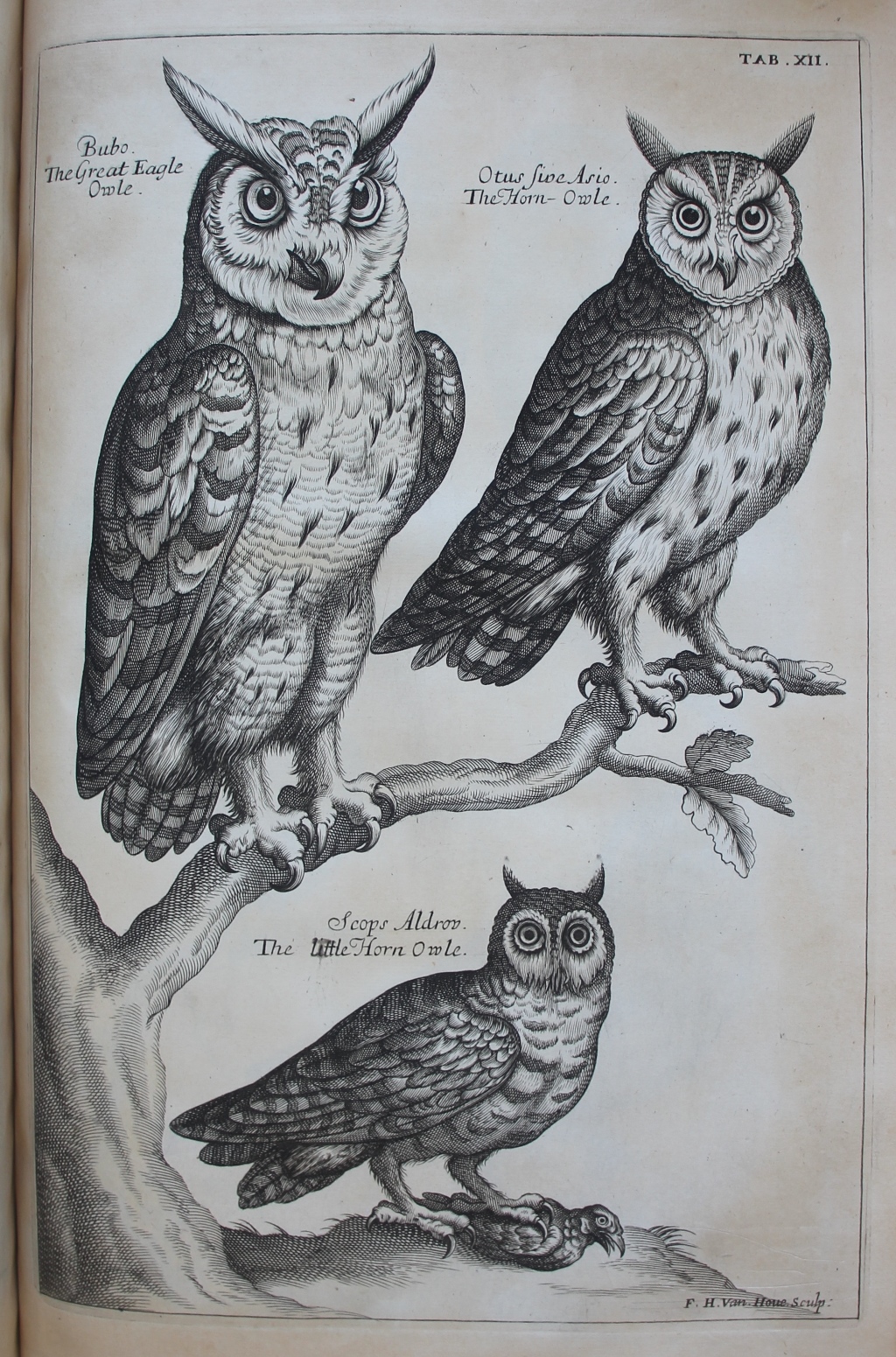

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XII: Owls.

Willughby and Ray included three plates featuring a parliament of owls. The owls on their first plate ranged from some of the largest to the smallest and concentrated on the three owls they called ‘The great Horn-Owl or Eagle-Owl’; ‘The Horn Owl, Otis sive Asio; and ‘The Little Horn Owl Scops Aldrov.’. As usual they began with the biggest, and reported what earlier authorities, such as Conrad Gessner (1516–65) and Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), had said about it. According to Gessner an eagle owl was:

As big or bigger than a Goose; had great Wings, two Feet, and three inches long, when extended in a right line from their beginning to the end of the longest feather, from the top of the uppermost bone of the Wing, to the lowest end was in a right line thirteen inches. The Head both for shape and bigness was like a Cats, for which reason the French do not improperly call it Chat huant [q. felis gemebunda.] Above each Ear stuck out black feathers, three inches high. The Eyes were great: The feathers about the Rump thick and very soft, of more than a fingers length, or an handful high, if my memory fail me not. From the point of the Bill to the end of the Feet or of the Tail (for they were both equally extended) it was two foot and seven inches long. The Irides of the Eyes were of a deep shining yellow or Saffron-colour. The Bill short, black, and hooked. The feathers being put aside the Ear-holes came into sight, which were great and open. On both sides by the Nosthrils grew hair-like feathers, as it were beards [barbulae.] The colour of the feathers all over the body was various, of whitish, black, and reddish spots. The length of the Leg was thirteen inches: The part above the knee thick and brawny: The Claws black, hooked, and very sharp: The Foot hairy or feathered down to the very Claws, the feathers being of a pale red’.[1]

Aldrovandi offered images of two others: the first, though it had much in common with Gessner’s eagle owl disagreed on details such as its claws, the colour of its wings, and ‘certain black strakes’ on its body; the second ‘was in all things like the second, save that the Legs were not hairy, and both Legs and Feet weak’.[2] Willughby and Ray were able to present eyewitness testimony of the last kind for they recorded that they had seen one in the royal palace at Bois de Vincennes, and two more at ‘his Majesties Park of St. James near Westminster’.[3] The eagle owls they saw in France and London were ‘as big as Eagles’ (hence their name).[4] Willughby and Ray described them in detail:

Their Legs and Feet hairy down to the Claws. They had three fore-toes in each foot; but the outmost of them was so framed that it could be turned backward, and made stand like a hind-toe. So that in that respect there is no difference between this and other sorts of Owls, but this may as well be said to have two back toes as they; whatever Aldrovandus hath delivered to the contrary. Their colour was much like to that of a Bittour, the feathers being marked with long black stroaks in the middle, the out-sides of a light bay. About the Belly some of the feathers were beautified with transverse lines. The Irides of the Eyes were of a reddish yellow or flame colour, [rather of a golden.][5]

On left: Eagle owl, Bubo bubo (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:2003.52.261 © NMI; in centre: Long-earred owl, Asio otus (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1900.123.1. © NMI; on right: Scops owl, Otus bakkamoena Pennant, 1769, NMINH:2003.52.1032. © NMI

Included in the same plate was one of the smallest owls, the Scops Owl, which Willughby and Ray noted was smaller than a pigeon.[6] However, while it was much smaller than an Eagle Owl (their Scops measured nine inches long), size was the main difference between it and an Eagle Owl (though there were some variations in colour). They noted that it was common in Italy and provided their readers with a graphic analysis:

Its Head is round like a Ball, covered with small soft feathers, all over of a lead-colour. The Bill short, hooked, and black. The Ears or feathers standing up in fashion of Ears, scarce appear in a dead bird, but are more manifest in a living, and consist only of one feather apiece. The chief colour of the whole body, as far as appears to sight, is cinereous, having here and there something of plumbeous mingled with it, curiously speckled with many white spots, more elegantly than any other Nocturnal Rapacious bird. In the greater feathers of the Wings and Tail it is marked with transverse white spots: All the other feathers besides these transverse marks are distinguished long-ways with a black line running through their middles. It is also besprinkled all over with a lovely tincture of red, especially about the Neck and the beginning of the Wings. The feathers on the Belly are whiter than elsewhere, the bottom or lower part of them, as also of all the rest, being black: particularly, these are red about the middle, else white, powdered with very small black specks. The Eyes like most other night-birds of a fiery shining Saffron colour: The Legs feathered, and of a reddish ash-colour: The Feet small, naked, scaly, approaching to a dark lead-colour, divided into two fore, and two back-toes, armed with dusky Claws.[7]

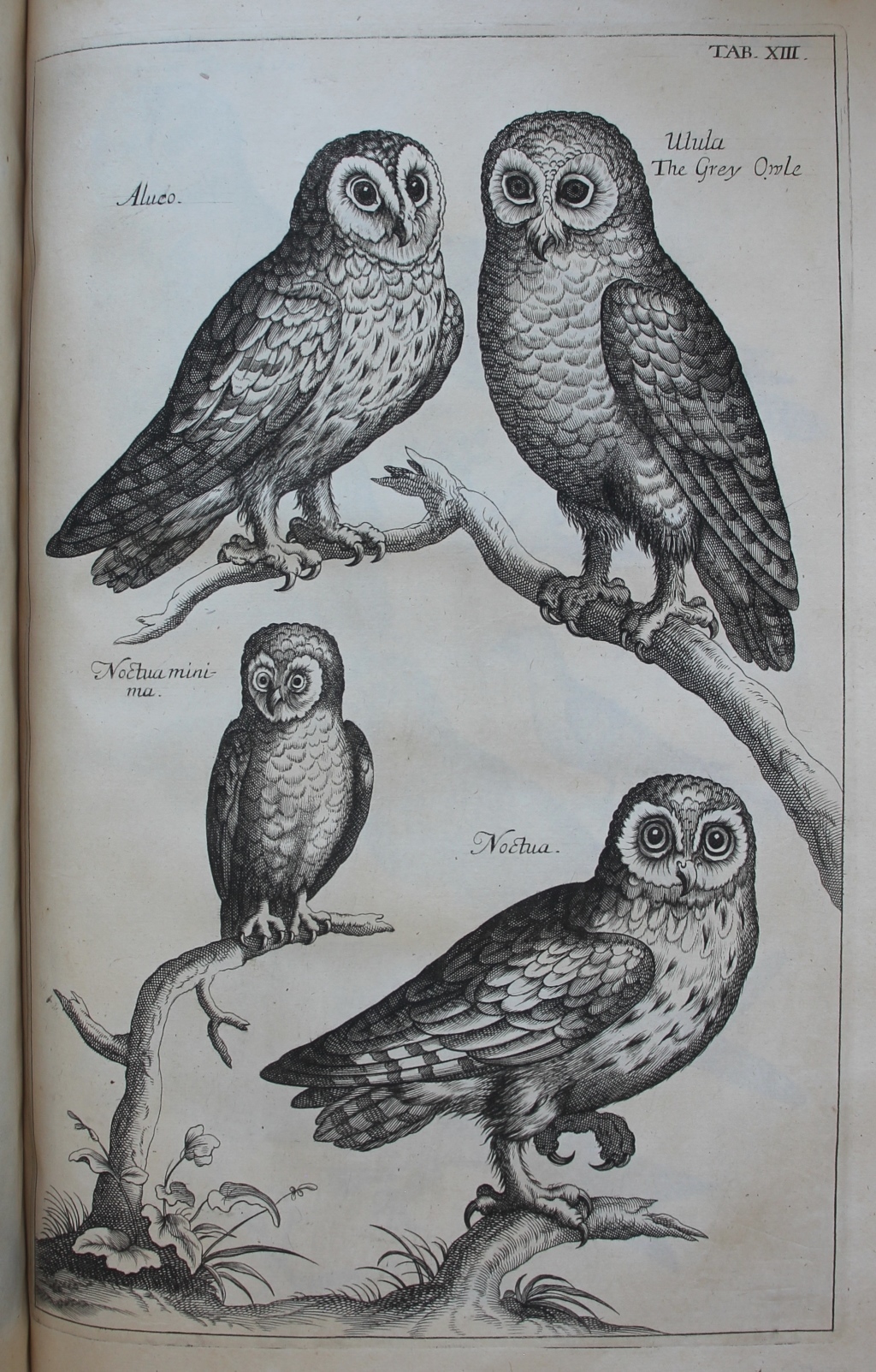

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XIII: Owls.

Perhaps the most recognisable owl is the Barn Owl, which Joannes Jonstonus (1603–75), had suggested was also called the ‘Church Owl’.[8] Willughby and Ray judged it to be about the size of a pigeon, giving precise measurements (from the tip of its bill to the tip of its tail was fourteen inches).[9] It is clear that though they referenced Aldrovandi in the naming of the bird, they had examined a Barn Owl themselves:

The Bill white, hooked at the end, more than an inch and half long: The Tongue a little divided at the tip; the Nosethrils oblong. A circle or wreath of white, soft, downy feathers encompassed with yellow ones, beginning from the Nosthrils on each side, passed round the Eyes and under the Chin, somewhat resembling a black hood, such as women use to wear: So that the Eyes were sunk in the middle of these feathers, as it were in the bottom of a Pit or Valley. At the interiour angle of each Eye the lower parts of these feathers were of a tawny colour. The Ears were covered with a Valve, which arises near the Eye, and falls backwards. The interiour circle we mentioned of white, downy feathers passed just over this Valve, so that part of them grew out of it. The Breast, Belly, and covert-feathers of the inside of the Wings were white, marked with a few quadrangular dark spots. The Head, Neck, and Back, as far as the prime feathers of the Wings, variously and of all Night-birds most elegantly coloured. The feathers toward the tips were waved with small whitish and blackish lines, resembling a grey colour; but about the shaft of each feather there was as it were a bed or row of black and white spots, situate long-ways, made up in some of two white and two black spots, in some of three of each colour, in some of but one.

Else the whole Plumage was of a dilute tawny or orange colour; which same colour was also the field or ground in the Wings and Tail. The master-feathers in each Wing were in number twenty four; whereof the greater have four transverse blackish bars. [In these bars in the exteriour Vane of the feather there is also white mingled with the black, which makes an appearance of a grey spot.] The intermediate spaces are fulvous, and powdered with small black specks; the tips of these feathers incline more to an ash-colour. The Wings when shut up extend full as far or further than the end of the Tail. In the exteriour Vanes of the first or outmost feather of each Wing the ends of the Pinnulae are not contiguous one to another, but stand at distance, like the teeth of a fine Comb. The Tail is made up of twelve feathers, of the same colour with the Wings, having four transverse black bars: four inches and half long. The interiour margins of the feathers both of Wings and Tail are white. The Legs are covered with a thick Down to the Feet, but the Toes are only hairy, the hairs also thin-set The Claw of the middle Toe is serrate on the inside as in Herons, but not so manifestly. It hath but one Toe that stands backward; but the outmost fore-toe may be turned so as to stand a little backward. The Guts were eighteen inches long; the blind Guts but two. It had a large Gall: Its Eggs were white.[10]

Their conclusions were in perfect agreement with Aldrovandi’s description of this bird.[11] Willughby and Ray were especially drawn to the eye of the Barn Owl: ‘The Eye in this Bird, and I suppose in all the rest of this kind, is of a strange and singular structure. That part which appears outwardly, though great, is only the Iris. For the whole bulb or ball of the Eye when taken out somewhat resembles a hat or Helmet, the Iris being the Crown, the part not appearing and extending it self good way further, the brims. The interiour edges of the Eye-lids round about are yellow. The Eyes are altogether fixt and immovable’.[12]

On left: Barn Owl, Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769), NMINH:1932.23.1. © NMI; on right: Little Owl, Athene noctua (Scopoli, 1769), NMINH:1903.180.1. © NMI

Their ‘Little Owl’, named after Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom who was often depicted with owls, according to their sources could be found in Austria, Italy and Germany. They themselves had bought one in a market in Vienna and hence were yet again able to provide their readers with the results of their own examination and dissection of the bird:

It was a Cock, scarce so big as a Blackbird. Its length from the Bill to the end of the tail was almost seven inches: Its breadth, the Wings being extended, more than fourteen inches. The Bill was white, and like to that of other Owls. The Tongue a little divided, as in the rest of this Tribe: The Palate below black, having a wide or gaping cleft, and below it a round hole: The Nosthrils oblong: The Ears great: The Eyes lesser and handsomer than in other Owls. The wreath or circle of feathers encompassing the face, beyond the Ears lesser, and less easily discernable. The upper part of the body was of a dark brown, with a mixture of red, having transverse whitish spots. The Tail was 2¾ inches long, compounded of twelve feathers exactly equal, having five or six transverse white bars. The feathers about the Ears were more variegated with black and white. The Chin and lower part of the belly white; The Breast marked with long dusky spots. The number of beam-feathers in each Wing was twenty four; their interiour webs were spotted with round white spots. It was feathered almost down to the Claws, excepting two or three annulary scales. The Feet were of a pale yellow. It had two back-toes, and as many foreones. The soals of the Feet were yellow; the Claws black: The inner side of the middle Claw is thinned into an edge. It had a great Gall; the length of the Guts was ten Inches; of the blind Guts one inch and a quarter.[13]

They noted the veracity of Gessner’s image – on which their own was based – and noted that they had also seen the birds for sale in Rome, where it was used to catch smaller birds.[14]

Since Aldrovandi had also described the bird in detail, Willughby and Ray decided to include his description also:

Aldrovandus hath described and figured for the Noctua is about the bigness of a Dove, nine inches long, hath a great Head, flat above; large, grey Eyes. The feathers of the whole body are partly of a pale Chesnut colour, partly distinguished with white. Through the extreme parts of the Wings, especially the prime feathers, it hath broad transverse lines or bars of a Chesnut colour. On the Belly it hath lines or spots of the same colour drawn longways, but inverted; the rest of the space or ground (the Heralds call it the field) being white. The Wings when withdrawn and closed reach as far as the end of the Tail. The Legs are feathered and rough down to the Feet, of a colour compounded of cinereous and Chesnut. The Toes are of a dark cinereous, bare of feathers, two standing each way. The Claws black, sharp, and crooked.[15]

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XIV: Owls et al. (including a black martin or swift).

Their last plate was a combination plate, also including other birds, and this may perhaps explain some confusion in the assortment. At the top left they label their image ‘Strix. Aldrovandi. The Brown or Screech Owl’. The image is certainly from Aldrovandi but the description makes it clear that Willughby and Ray were talking about a Tawny (also known as a Brown Owl), which is common in Europe, rather than an Eastern Screech Owl, which is normally found in the Americas:

It hath huge Eyes, at least twice so big as those of the Barn or white Owl, and protuberant. It had Membranes for Nictation, drawn from above downwards, having black edges. The borders of the Eye-lids were broader than ordinary, and their edges red. The Ear-holes were three times as great as in the white Owl, and covered with Valves. A circle of feathers encompasses the Eyes and Chin, like a womans hood, as in the Barn-Owl , but not standing up so high as in that. This circle or hood consists of a double row of feathers, the exteriour more rigid, variegated with white, black, and red; the interiour consisting of soft feathers, of a white mingled with a flame-colour. The middle part of the head without the hood is of a dark brown. The exteriour circle of the hood compasses the ears; the greatest part of the interiour feathers of it, where it passes the ears, grows out of the covers of the Ears. The Eyes in this Bird are nearer to the Ears than in any other Animal I know. Beyond the Nosthrils and below the Eyes grew bristly feathers having black shafts. The back and upper side of the body was particoloured of ferrugineous and dark brown, the black taking up the middle part of each feather, and the ferrugineous the out-sides. If one curiously view and observe each single feather, one shall find them waved with transverse lines, cinereous and brown alternately succeeding each other. The belly and lower side of the body is of the same colour with the back, but more dilute with a mixture of white. The bottoms of all the feathers are black.[16]

Nightjar, Caprimulgus europaeus (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1909.266.1. © NMI

In the same plate Willughby and Ray included another ‘owl’ which they named ‘The Fern-Owl, or Churn-Owl, or Goat-sucker, Caprimulgus’, and which they stated was to be ‘found in the Mountainous Woods, especially in many places of England, as in York-shire, Derby-shire, Shrop-shire’.[17] Yet again they provided a detailed description – but this time there was a note of uncertainty, for they included a number of features which undermined their classification: its head was much smaller than other owls and it differed in colouring, for the colour of its feathers were ‘more like to a Cuckow than an Owl’.[18] Their hesitation was well-founded as it seems likely that their ‘Churn-Owl’ was actually a nightjar![19]

Dominique Crowley: Monstrorum, RHA Ashford Gallery

Dominique Crowley, Owl, Vignette, 2024, oil and acrylic resin on wood panel, 40cm x 40cm. Bird: Short Eared Owl. © Dominique Crowley 2024, image courtesy of the artist).

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617).

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 99. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[2] Ibid., p. 100.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., p. 101.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., p. 22.

[9] Ibid., p. 104.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., pp 105–6.

[14] Ibid., p. 106. See Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), p. 559.

[15] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick. p. 106.

[16] Ibid., p. 102.

[17] Ibid., p. 107.

[18] Ibid.

[19] I am grateful to Dr Paolo Viscardi, Keeper of Natural History at the National Museum of Ireland, for this identification.