Dead Dodos

‘In the dark of an early morning in 1667, say, during a rainstorm, she took cover beneath a cold stone ledge at the base of one of the Black River cliffs. She drew her head down against her body, fluffed her feathers for warmth, squinted in patient misery. She waited. She didn’t know it, nor did anyone else, but she was the only dodo on Earth. When the storm passed, she never opened her eyes. This is extinction’.

David Quammen, The Song of the Dodo.[1]

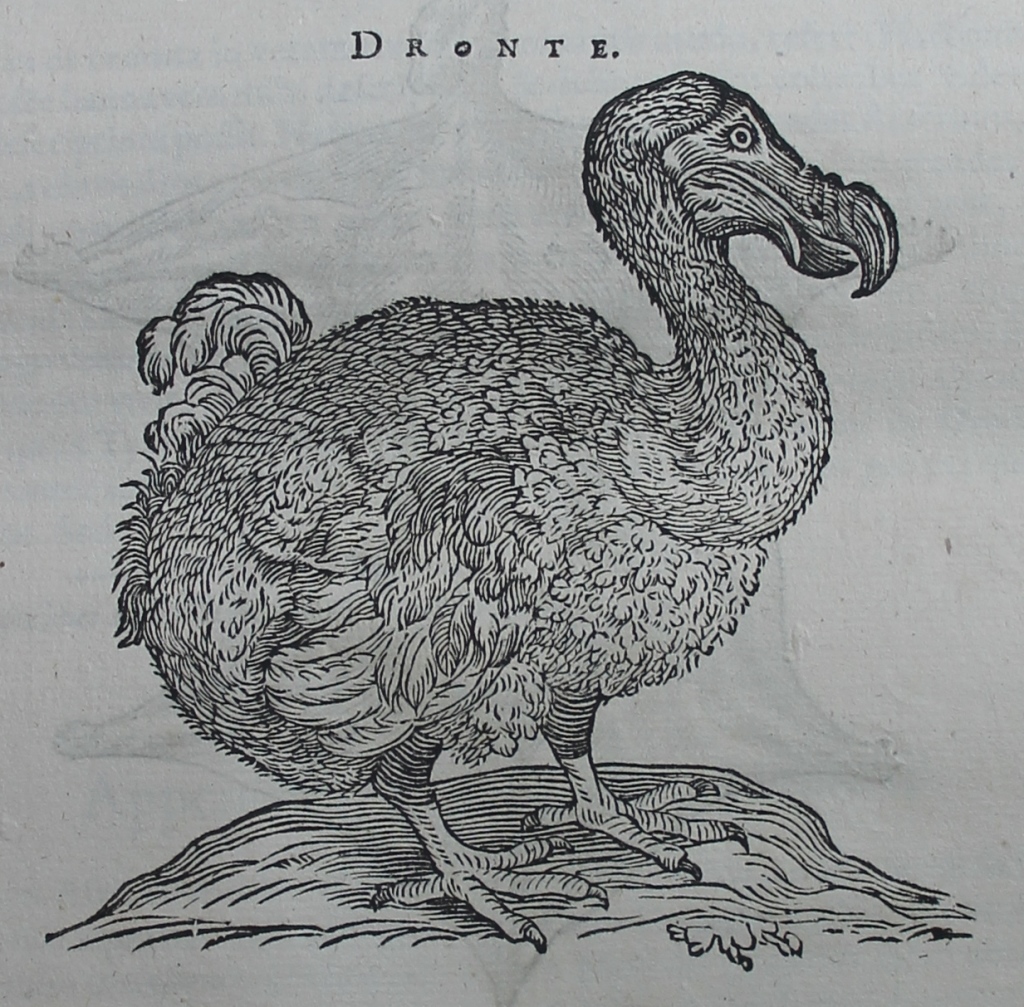

Charles de L’Ecluse (Carolus Clusius), Exoticorum libri decem: quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiæ describuntur: item Petri Bellonii observationes eodem Carolo Clusio interprete (Antwerp, 1605), p. 100: Dodo.

Hume rightly says that the dodo is perhaps the most written about bird in the world.[2] The ‘rediscovery’ of Mauritius in 1598 by the Dutch East India Company fuelled fascination with this unusual bird, for the accounts brought back to the Netherlands by Dutch sailors soon found their way into print. The earliest account was by Vice-Admiral Wybrant Warwijck who had sailed in the flotilla of Admiral Jacob Cornelisz. van Neck (1564–1638), in 1598. This 1598 account was sketchy, mentioning only that they have found ‘large birds, with wings as large as of a pigeon, so that they could not fly and were named penguins by the Portuguese’.[3]

More accounts followed but the first truly scientific account of the dodo was provided by the Flemish physician and botanist Carolus Clusius (1526–1609).[4] This appeared in his seminal Exoticorum libri decem: quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiæ describuntur: item Petri Bellonii observationes eodem Carolo Clusio interprete (Antwerp, 1605), which Worth owned, and in it Clusius decided to place the dodo, which he called ‘Gallinaceus Gallus peregrinus’, in Book V, chapter IV, along with other flightless birds (the section on the dodo is between his discussion of a cassowary and a penguin).

Clusius included the above woodcut of a dodo, reputedly based on an image from a diary of the 1598 voyage, and this image was soon replicated.[5] It was not the only one for soon live dodos were being included (and painted) in the imperial menagerie of Emperor Rudolf II (1552–1612), and there was at least one other in London in 1638 (judging by the account of Sir Hamon L’Estrange).[6] Body parts also found their way into the collections of collectors of curiosities: in the Netherlands the Dutch physician and scientist Bernard Paludanus (1550–1633), obtained a skull of a dodo (now known as the ‘Copenhagen skull’), and Pieter Paaw (1564–1617), Professor of Medicine at the University of Leiden, acquired a leg of a dodo, which Clusius would later describe in his Exoticorum libri decem. In England it seems likely that the live bird viewed in 1638 may have been the property of John Tradescant the Younger (1608–62), who later became gardener to King Charles II (1630–85), and who had a museum at Lambeth. By 1659 the Tradescant collection (including items collected by his father John Tradescant the Elder (c. 1570–1638)), had become an important part of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. It was probably in Oxford that Francis Willughby (1635–72) and John Ray (1627–1705), saw a dodo but by that time it was long dead for Ray mentioned that ‘We have seen this Bird dried, or its skin stuft in Tradescants Cabinet’.[7] Only bits of the Oxford dodo survive today, now housed in the University Museum of Natural History, Oxford.

Clusius offers his readers the following description:

Moreover, that foreign [peregrina] bird indeed equalled a swan in size or it exceeded it, but its form was very different: since its head was large, covered as if with a membrane resembling a hood; the beak was not flat, but thick and oblong, yellowish color in the part near the head, with the extreme point black, upper part of it bent hooked and curved, actually, on the inferior or on that lying face upwards, a bluish spot occupied the median part between the yellow and black. They said that [this bird] was covered in thin/few and short feathers, and that it lacked wings, but has in their place at least four or five rather long black feathers: the posterior part of the body was very fat and very thick, in place of a tail there were four or five curled rolled around small feathers of ash colour; its legs were rather thick than long, their upper part to the knee was covered in black feathers, the inferior [part] with the feet was of yellowish colour; the feet certainly were divided into four toes, the three longer directly anteriorly, the fourth shorter turned posteriorly, all of them furnished with black claws.[8]

In the above account Clusius was clearly relaying information he had received from the various accounts provided by Dutch sailors who had seen the bird but in his next section he added direct eye witness testimony for he had the opportunity to examine the leg of the Dodo which belonged to his colleague Pieter Paaw:

But after I put together and described as faithfully as I could the history of this bird, I happened to see its leg [crus] cut off as far as the knee, at the house of that most illustrious man Petrus Pawius Primary Professor of Medicine in the University of Leiden, recently brought out of Mauritius Island. It was but not very long, from the knee all the way to the bending of the foot a little more than four inches only; its thickness, however, was great, being almost four inches in circumference, and was covered in thick skin as scales, in the front part wider and yellow, on the back, however, smaller and dusky; besides the upper part of the toes was also furnished with broad single scales, but on the back these were totally callous: the toes were short enough for such a thick leg; for the length of the largest or middle to the claw was not much over two inches, the other two next to it were scarcely an inch, the posterior an inch and a half; however, all claws thick, hard, black, less than an inch in length, but that of the posterior tow was longer than the rest, and over an inch.[9]

Clusius also reported on what the sailors had said about the taste of the bird (always a source of interest in the early modern period):

Sailors name this bird in their language Walgh-vogel, that is, nauseating bird, partly because from after long boiling its flesh did not become more tender, but remained hard and difficult to digest (except its breast and stomach, which were ascertained to be no despicable flavour) [and] partly because they could get many turtledoves, which were found to be delicate and more pleasant to the palate …[10]

Clusius was, however, far more interested in the stones that had been found in the stomach of dodos and which he had viewed at the house of Christian Porret (fl. 1605), an apothecary based in Leiden:

They were of different forms, one flat and round, the other irregular and angular, an inch in size, which is figured next to the feet of this bird, the latter larger and heavier, and both of ash colour; it is probable that they were picked up by this bird on the seashore, and then they were devoured, not formed in its stomach.[11]

In fact, he depicted one of these stones beside his dodo – which may be seen in the image above.

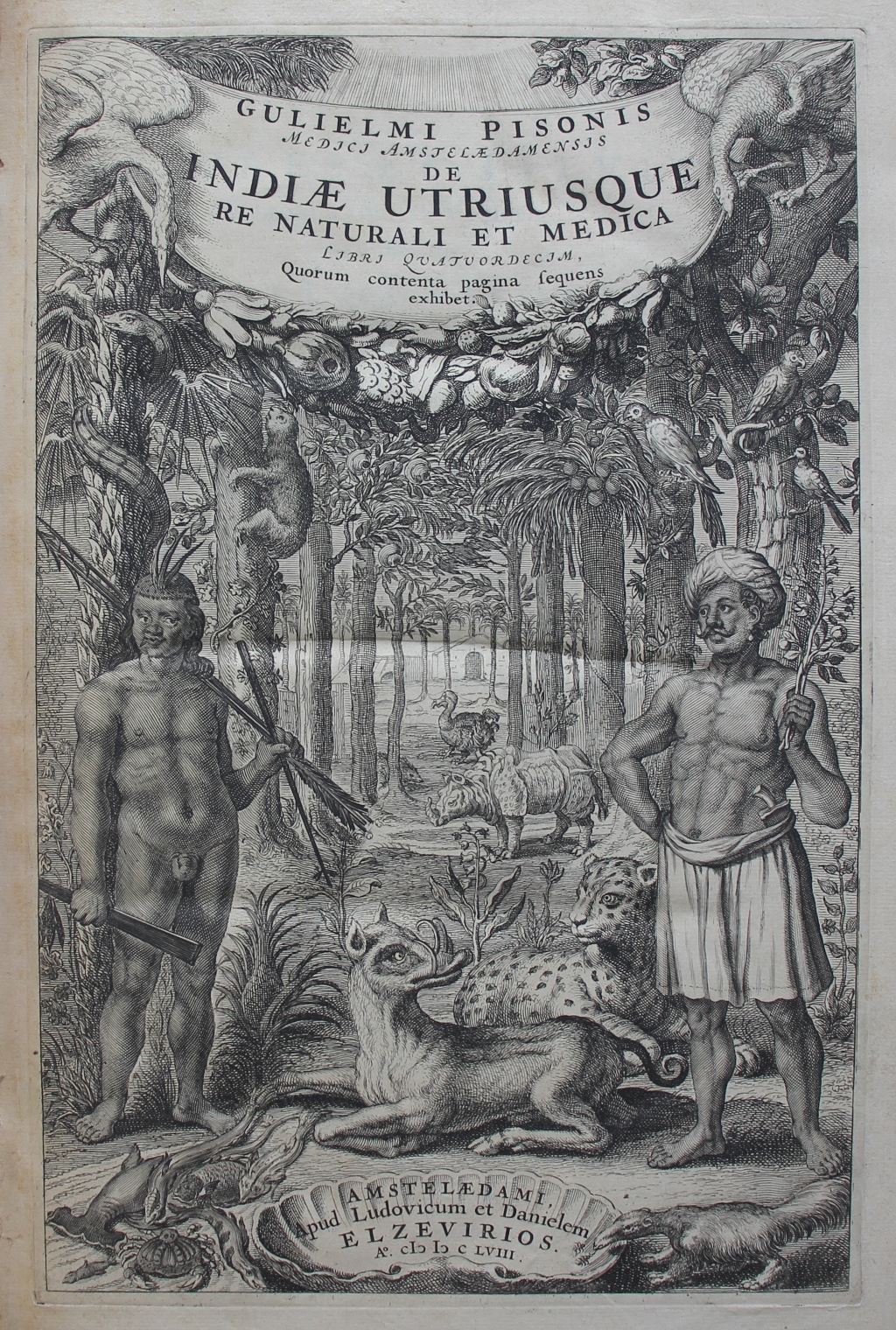

Willem Piso, De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), title page.

If Worth wanted to hear more about dodos he had only to reach for his copy of Willem Piso’s De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), which included Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex’ by the Dutch physician Jacob de Bondt (1592–1631), who had travelled to Indonesia as part of the Dutch East India Company. Piso (1611–78), another Dutch physician, but in his case one who had been in the train of the Dutch West India Company, had decided to add De Bondt’s text to Historia Naturalis Brasiliae, an important text on the natural history of Brazil which was the work not only of Piso but also the German polymath Georg Marcgraf (1610–c. 1643/4), and which had appeared ten years previously. By adding De Bondt’s text Piso could rightly claim that the work covered the natural history of the two Indies. To bring home the point, Piso changed the engraved title page of the 1658 edition to include some of the amazing animals and birds discussed by De Bondt and in pride of place, right in the centre of the page, we can see the dodo. Certainly the dodo of Mauritius fitted in very well with other flightless birds which De Bondt had encountered on his travels, such as the cassowary he found in Indonesia.[12]

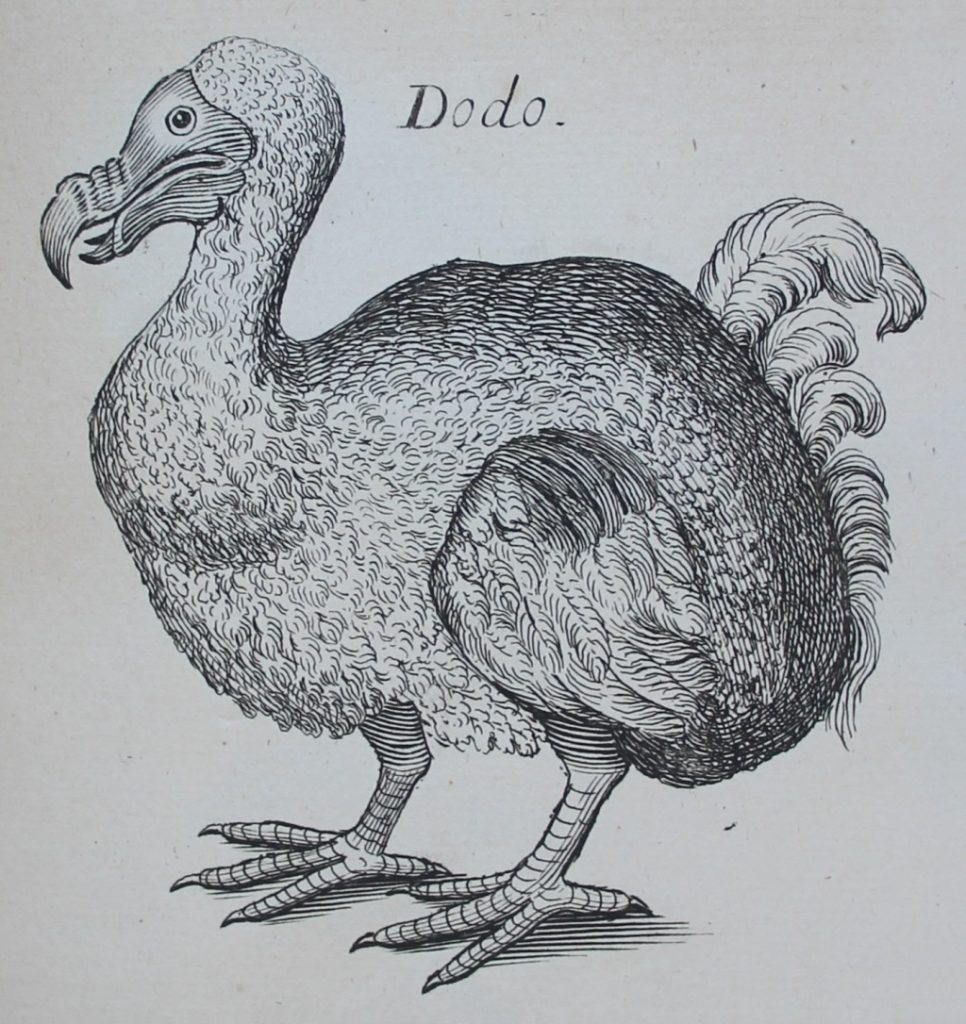

Willem Piso’s commentary on Jakob de Bondt’s ‘Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex’ in Willem Piso, De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), p. 70: Dodo.

De Bondt provides his readers with the following description of what he calls ‘The Dronte or Dod-aers’:

Among the East Indian Islands is considered that which by others is called Cerne; the name agreed on by those of our country is Mauritius, chiefly famous on account of its black ebony. In this island a bird of wonderful form named Dronte is numerous. Of the size between an ostrich and Indian hen [turkey], from which it partly differs in shape, and partly agrees, especially with the African ostrich, if one considers the rump, feathers, and plumes; so that it appears as if a pygmy among, if one regards the shortness of the legs.

In other respects, the head is very large, deformed, covered by a membrane, resembling a cowl. The eye large, black; neck curved, prominent, fat; beak long beyond proportion, strong, of bluish white, except the extremities, of which the lower is black, the upper yellowish, both sharp pointed and hooked. The gape hideous, greatly broad, as if formed for gluttony. Body obese, rotund, clothed in soft grey plumes, in the manner of ostriches; adorned on both sides, in place of quills, with small feathered wings of yellow-ash, and behind the rump, in place of the tail, five wavy feathers of the same colour. Legs are yellow, thick, but very short: four pedal digits are stout, long, scaled, all having strong black claws attached.[13]

Unlike the Huguenot François Le Guat (1637–1735), whose sympathy for the flightless Solitaire of Rodrigues Island was obvious in his Voyage et avantures de François Leguat, & de ses compagnons, en deux isles desertes des Indes Orientales. Avec la Rélation des choses les plus remarquables qu’ils ont observées dans L’Isle Maurice, à Batavia, au Cap de Bonne-Esperance, dans L’Isle St. Helene, & en d’autres endroits de leur Route. Le tout enrichi de cartes & de figures (London, 1708), De Bondt apparently held the dodo in contempt : in his eyes the bird was ‘slow going and stupid, and easily taken by hunters’, who sometimes regretted their hunting as the meat of the bird, was, as previous Dutch sailors had complained, ‘difficult of digestion’.[14] Like Clusius, De Bondt was also interested in the mysterious stones found in the stomachs of the birds but he did not depict it. It was of interest to him because it linked the dodo with the ostrich, another bird who was reputed to swallow ‘hard things’.[15]

The section in De Bondt’s Historiæ Naturalis & Medicæ Indiæ Orientalis libri sex certainly reads as an eye witness account but did De Bondt actually see a dodo? Paris points out that the entry on the ‘Dronte’ is not present in a manuscript copy of De Bondt’s work and it is possible that the text was a later addition by Piso (who certainly had not seen a dodo himself), from earlier texts.[16] As Lawrence notes, it bore certain similarities with earlier written accounts and included some of Clusius’s observations, but it was not a new eye witness account – rather it was ‘old material used in a new way’.[17] Controversy also reigns over the image, which Paris (and Lawrence) suggest may have been based on a painting of a dodo by the artist Roelandt Savary (1576–1639).[18] What was being created was not an account of an encounter with an actual bird, but a presentation of a bird, in this case the dodo, as a symbol of empire. As Lawrence notes: ‘Piso was including a ‘set-piece’ animal, made up of images demonstrating the Dutch influence across the Indian Ocean world’.[19]

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate XXVII: detail of a dodo.

When Willughby and Ray decided to add an image and description of this famous bird to their Ornithologia libri tres of 1676, they therefore had a variety of accounts from which to choose – a circumstance noted by them in the title of their section on the dodo: ‘The Dodo, called by Clusius Gallus gallinaceus peregrinus, by Nieremberg Cygnus cucullatus, by Bontius Dronte’. As we have seen in the case of Nieremberg’s description of a penguin, his text and image was heavily reliant on that of Clusius and the same was true of his description of a dodo. For this reason Willughby and Ray concentrate on the two most widely available descriptions: those of Clusius and De Bondt.

This is clearly visible in their description of a dodo which at times copies Clusius and De Bondt’s accounts verbatim:

This Exotic Bird, found by the Hollanders in the Island called Cygnaea or Cerne by the Portugues, Mauritius Island by the Low Dutch, of thirty miles compass, famous especially for black Ebony, did equal or exceed a Swan in bigness, but was of a far different shape: For its Head was great, covered as it were with a certain membrane resembling a hood: Beside, its Bill was not flat and broad, but thick and long; of a yellowish colour next the Head, the point being black: The upper Chap was hooked; in the nether had a bluish spot in the middle between the yellow and black part. They reported that it is covered with thin and short feathers, and wants Wings, instead whereof it hath only four or five long, black feathers; that the hinder part of the body is very fat and fleshy, wherein for the Tail were four or five small curled feathers, twirled up together, of an ash-colour. Its Legs are thick rather than long, whose upper part, as far as the knee, is covered with black feathers; the lower part, together with the Feet, of a yellowish colour: Its Feet divided into four toes, three (and those the longer) standing forward, the fourth and shortest backward; all furnished with black Claws.[20]

Indeed their account of the dodo’s leg, the sailors’ name for the bird and the gastrolith is literally taken word for word from that of Clusius for it was Clusius who had the chance to examine the dodo’s leg owned by Pieter Paaw.

The same is true of their account from De Bondt’s treatise:

Bontius writes, that this Bird is for bigness of mean size, between an Ostrich and a Turkey, from which it partly differs in shape, and partly agrees with them, especially with the African Ostriches, if you consider the Rump, quils, and feathers: So that it shews like a Pigmy among them, if you regard the shortness of its Legs. It hath a great, ill-favoured Head, covered with a kind of membrane resembling a hood: Great, black Eyes, a bending, prominent, fat Neck: An extraordinary long, strong, bluish white Bill, only the ends of each Mandible are of a different colour, that of the upper black, that of the nether yellowish, both sharp-pointed and crooked. It gapes huge wide, as being naturally very voracious. Its body is fat, round, covered with soft, grey feathers, after the manner of an Ostriches: In each side instead of hard Wing-feathers or quils, it is furnished with small soft-feathered Wings, of a yellowish ash-colour; and behind the Rump, instead of a Tail, is adorned with five small curled feathers of the same colour. It hath yellow Legs, thick, but very short; four Toes in each foot, solid, long, as it were scaly, armed with strong, black Claws. It is a slow-paced and stupid bird, and which easily becomes a prey to the Fowlers. The flesh, especially of the Breast, is fat, esculent, and so copious, that three or four Dodos will sometimes suffice to fill an hundred Seamens bellies. If they be old, or not well boyled, they are of difficult concoction, and are salted and stored up for provision of victual. There are found in their stomachs stones of an ash-colour of divers figures and magnitudes; yet not bred there as the common people and Seamen fancy, but swallowed by the Bird; as though by this mark also Nature would manifest, that these Fowl are of the Ostrich kind in that they swallow any hard things, though they do not digest them. Thus Bontius.[21]

However, Willughby and Ray had one advantage over De Bondt – like Clusius they had the opportunity to see a dried and stuffed bird in Tradescant’s collection at Oxford and it seems likely that their image of a dodo is based on the Tradescant bird.[22]

By the time Willughby and Ray’s Ornithologia appeared in 1676 to revolutionise the classification of birds, the dodos were already in decline. We do not know exactly when the dodo became extinct. Though hunting was one factor in their demise, there were others, for the ship rats Rattus rattus, once they arrived in Mauritius, proved to be as much if not a greater threat to dodos for they not only attacked nests, but were also competitors for food.[23] As Hume notes, the introduction of other animals to the island by humans, especially pigs, would prove to be especially detrimental to the ground nesting dodos.[24] There were sightings of dodos on Mauritius while the island was under the command of Opperhoofd Isaac Joan Lamortius, whose tenure as Dutch East India Company commander on Mauritius was the longest (1677–92), but by this time they were becoming rare and though there was a reputed sighting in 1688 it is, as Hume notes, unclear whether the bird sighted was in fact a dodo.[25]

The mid nineteenth-century witnessed a search for dodo bones on Mauritius and these digs not only yielded dodo bones but also pointed to the existence of other extinct birds on Mauritius. As Hume et al, note, as a result of these archaeological digs Victorians expanded their list of extinct birds to include the Rodrigues Night Heron Nycticorax megacephalus, the Rodrigues Rail Erythromachus leguati, the Rodrigues Turtle Dove Nesoenas rodericana, the Rodrigues Parrot Necropsittacus rodericanus and the Rodrigues Lizard Owl Mascarenotus murivorus.[26]

Climate Change

On the left is a skeleton of a solitaire, Pezophaps solitaria, NMINGF21701, and on the right, a skeleton of a dodo, Raphus cucullatus, NMINGF21700. © NMI

The dodo, with its cousin the solitaire on Rodrigues Island, and the great auk in the far north, all became extinct due to human interventions. Flightless birds such as the dodo and solitaire, who had been secure on their islands, were easy game for the humans who arrived there, and the animals in their train. Moss notes that ‘Recent studies have shown that birds found on oceanic islands have a forty times greater chance of being threatened by extinction than those living on larger, continental landmasses. As a result, of all the world’s threatened bird species, 39 per cent are confined to islands’.[27]

Today humans might not actively hunt such birds but we are still having a major impact on bird populations by our actions. As Moss argues, ‘The dodo’s disappearance heralded what has become known as ‘the Age of Extinctions’.[28] The dodo, which along with the solitaire of Rodrigues Island, are members of the Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves), which is one of the biggest bird families. As Moss reports, it is a huge bird family with almost 350 species but already 21 of these species have gone extinct.[29]

Pigeons and doves are not the only birds at risk. In 2006, in a World Wildlife Fund report on the potential impact of climate change on bird species, Wormworth and Mallon pointed to the numerous direct and indirect ways climate change affects birds, changes which were already evident nearly twenty years ago: for example, seasonal shifts in timing greatly impact on nesting and migration.[30] They noted that already, in 2006, there was strong evidence that birds were ‘already shifting their range boundaries pole-ward’.[31] They advised that birds which were dependent on specific habitats would be at particular risk unless they could somehow adapt to new environments.[32] They noted that many species were attempting to adapt – and this was supported by studies which examined shifting patterns in the timing of migrations, mating, nest-building, egg-laying and even clutch size.[33] By 2006, already in the UK, ‘between 26 per cent and 72 per cent of recorded migrant bird species have earlier spring arrival’ – some of them up to two weeks earlier.[34] Since 2006 we have witnessed a host of ways in which birds are being impacted by climate change. As Tim Birkhead reminded us in 2023, climate change affects not only their diet on land but also at sea, with changing patterns in plankton leading to a noticeable decline in puffins in the far north: Norway, Iceland, the Faroes Islands and the north of Scotland.[35] Puffins are not alone in their plight: populations of Common Guillemots in roughly the same area (Norway, Iceland and the Faroes), are likewise plummeting. And that is the tip of the iceberg because according to the International Fund for Animal Welfare, many of the 10,000 bird species with whom we are lucky to share our planet, are now ‘on the brink of extinction’.[36] Birds are, as Wormworth and Mallon stated in 2006, ‘highly sensitive to climate and weather’, and thus are literally the ‘canaries in the cool mine’ for what is happening to our natural world.[37]

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Anon., ‘19 of the World’s most endangered birds in 2025’, International Fund for Animal Welfare, 4 June 2025.

Birkhead, Tim, Birds and Us: A 12,000-Year History, from Cave Art to Conservation (London, 2023).

Hume, Julian, ‘The history of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius’, Historical Biology, 18, no. 2 (2006), 65–89.

Hume, J. P., L. Steel, A. A. André and A. Meunier, ‘In the footsteps of the bone collectors: nineteenth-century cave exploration on Rodrigues Island, Indian Ocean’, Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology, 27, no. 2 (2015), 265–86.

Lawrence, Natalie, ‘Assembling the dodo in early modern natural history’, British Society for the History of Science, 48, no. 3 (2015), 387–408.

Moss, Stephen, Ten birds that changed the world (London, 2023).

Ommen, Kasper van, The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609: Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009. With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond (Leiden, 2009).

Paris, Jolyon C., The dodo and the solitaire: a natural history (Bloomington, Indiana, 2013).

Rodriguez-Pontes, Martin A., ‘Digital reconstruction of Rodrigues Solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria) (Aves: Columbidae) physical appearance based on early descriptive observation and other evidence’, Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology, 28, no. 3 (2016), 398–414.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

Wormworth, Janice, and Karl Mallon, Bird species and climate change: The Global Status Report: a synthesis of current scientific understanding of anthropogenic climate change impacts on global bird species now, and projected future effect (Sydney, 2006).

__

[1] Quoted in Moss, Stephen, Ten birds that changed the world (London, 2023), p. 136.

[2] Hume, Julian, ‘The history of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius’, Historical Biology, 18, no. 2 (2006), 65.

[3] Ibid., 67.

[4] Paris, Jolyon C., The dodo and the solitaire: a natural history (Bloomington, Indiana, 2013), kindle edition.

[5] Hume, ‘The history of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius’, 73. Clusius mentions this in his Exoticorum libri decem: ‘Meanwhile, while they were abiding on the island, they observed birds of a varied type; among those one very strange, of which [I saw] a rough small figure sketched in the journal containing the whole history of that voyage, which on their return they undertook to portray which is set forth in this chapter’. English translation from Paris, The dodo and the solitaire, kindle edition.

[6] Hume, ‘The history of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius’, 79. See also Moss, Stephen, Ten birds that changed the world (London, 2023), p. 120.

[7] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 154. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[8] Paris, The dodo and the solitaire, kindle edition.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.; On Porret see Ommen, Kasper van, The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609: Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009. With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond (Leiden, 2009), p. 9.

[12] To find out more about Piso and De Bondt’s texts see the Flightless Birds webpage.

[13] Paris, The dodo and the solitaire, kindle edition.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Lawrence, Natalie, ‘Assembling the dodo in early modern natural history’, British Society for the History of Science, 48, no. 3 (2015), 388, 395.

[18] Paris, The dodo and the solitaire, kindle edition.

[19] Lawrence, ‘Assembling the dodo in early modern natural history’, 397.

[20] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books …, p. 153. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[21] Ibid., pp 153–4.

[22] Ibid., p. 154.

[23] Hume, ‘The history of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius’, 82.

[24] Ibid., 83.

[25] Ibid., 84.

[26] Hume, J. P., L. Steel, A. A. André and A. Meunier, ‘In the footsteps of the bone collectors: nineteenth-century cave exploration on Rodrigues Island, Indian Ocean’, Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology, 27, no. 2 (2015), 282.

[27] Moss, Ten birds that changed the world, p. 127.

[28] Ibid., p. 114.

[29] Ibid., pp 116–7.

[30] See Wormworth, Janice, and Karl Mallon, Bird species and climate change: The Global Status Report: a synthesis of current scientific understanding of anthropogenic climate change impacts on global bird species now, and projected future effect (Sydney, 2006).

[31] Ibid., p. 7.

[32] Ibid., p. 9.

[33] Ibid., p. 18.

[34] Ibid., p. 19.

[35] Birkhead, Tim, Birds and Us: A 12,000-Year History, from Cave Art to Conservation (London, 2023), p. 169–70.

[36] Anon., ‘19 of the World’s most endangered birds in 2025’, International Fund for Animal Welfare, 4 June 2025.

[37] Wormworth and Mallon, Bird species and climate change, p. 6.