Exotic Birds

In the early modern period ‘exotic’ birds were transported to Europe from the far corners of the globe. As Swan notes, their exoticism lay in the fact that they came from far away lands, and hence were highly valued objects which instilled wonder in their viewers.[1] Perhaps none were as famous as the birds of paradise, native to New Guinea and the Maluku Islands, which were brought back as skins in the first decades of the sixteenth century.

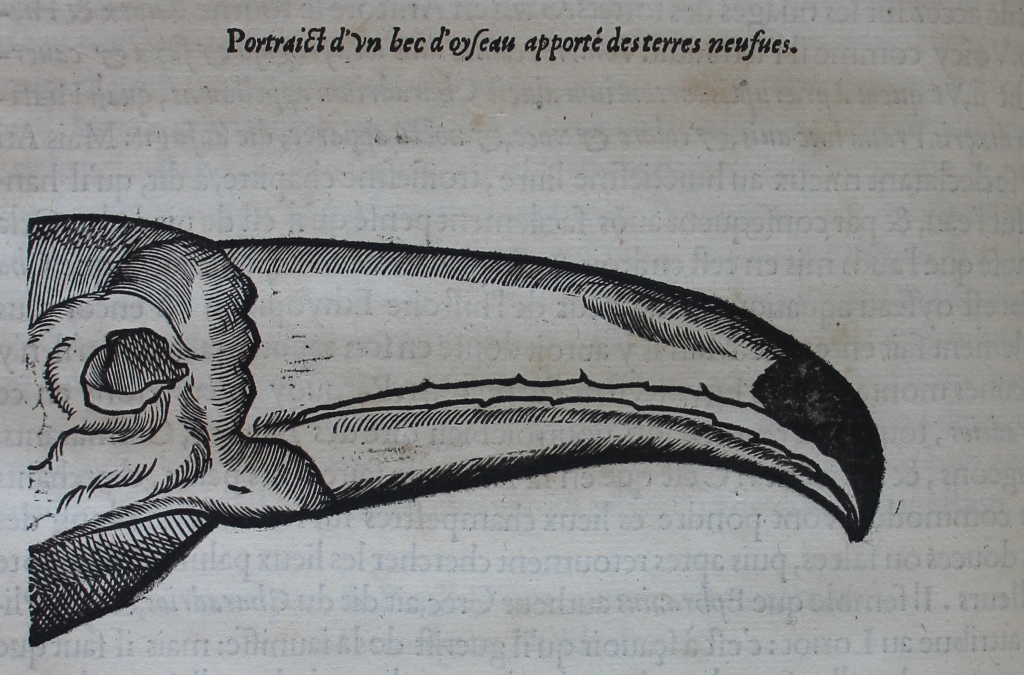

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 184: toucan bill.

In general Pierre Belon (1517–64), the author of one of the earliest and most important ornithological textbooks, said little about birds from the New World, preferring to concentrate on more familiar birds. However, as this image demonstrates, he could not resist the temptation to include images of some of the most famous exotic birds. It is clear from his caption that he was unsure about the name of this unusual bird with such a strange beak: all he could be sure of was that it was a beak of a bird from the New World and one moreover which had been unknown to ancient authors. This description of this bill of a Toco Toucan (Ramphastos toco), would prove influential.[2] As Asúa and French suggest, he probably acquired this toucan beak from a sailor, given the trade in such objects.[3] It was not the only bird he acquired in this manner, for the plumage of his ‘merle de bresil’ (Brazilian tanager), was bought in the same way.[4]

Toucan, Ramphastos (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:2003.52.350. © NMI

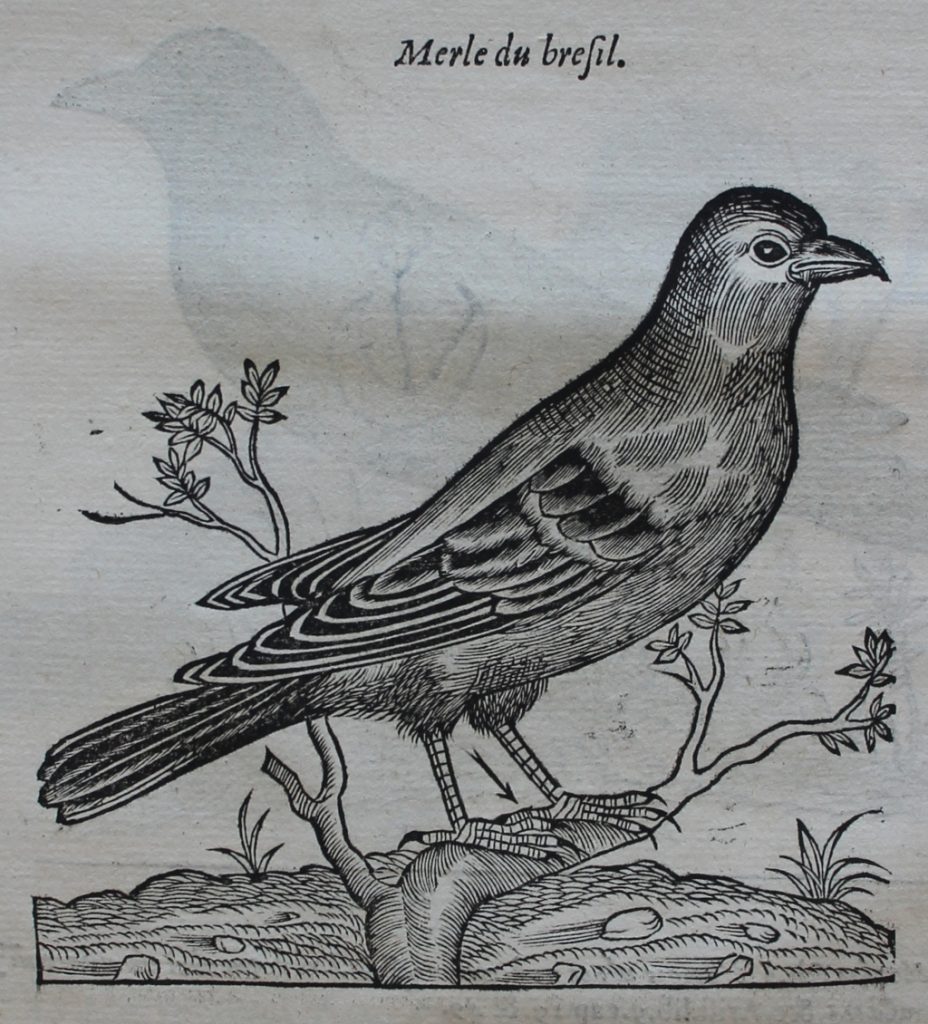

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 319: Brazilian tanager.

Classifying new species from the New World posed a number of challenges for many of these birds did not survive the sea journey and therefore European-based commentators were forced to either rely on images or preserved dead birds.[5] This certainly presented problems for ornithologists such as Belon when attempting to describe and depict birds from the New World, for while they could describe them in words, often the accompanying woodcut might leave much to be desired, not least because it could not replicate the beautiful colours of the original. Belon was well aware of this problem, commenting on it in his ‘Preface to the Reader’:

Consequently, if there are such strong similarities between the beings, how should the Reader then make distinctions between one and other only with a picture but without colour? He who makes a portrait of a little bird, can easily use it for 30 others, if he uses the right colours: because, almost all have the same legs, claws, eyes, beaks, and feathers, which don’t differ if not for the colour. This thought brought us to the decision to colour the portraits.[6]

However, hand colouring was a time-consuming and costly process, not to mention that the colouring might not accurately represent the bird. Most copies of Belon were not coloured and certainly Worth’s copy is un-coloured. Colour, a crucial factor in identification of birds could, however, be addressed in the accompanying text and Kleiter rightly suggests that in Belon’s case word and image were intrinsically connected.[7] This is clearly apparent in Belon’s commentary on the ‘Merle du Brasil’, the Brazilian tanager (Ramphocelus bresilius), a bird which he certainly did not see alive.

Dominique Crowley: Monstrorum, RHA Ashford Gallery

Dominique Crowley, Memento II, 2024, oil and acrylic resin on wood panel, 80cm x 80cm. Birds: Scarlet Tanager, Blue-grey Tanager, Venezuelan Troupial, Purple Honeycreeper. © Dominique Crowley 2024, image courtesy of the artist.

Belon made much of the fact that his images were drawn ‘ad vivum’ (‘from life’), but in this context, this was simply not possible: all Belon could do was present the most accurate image possible, and this he attempted to do. The Brazilian tanager, like other birds from the New World, was included by Belon because he had access to a preserved bird: one which Kleiter suggests, was probably preserved by the indigenous peoples of Brazil for shipment to Europe.[8] As Belon noted in his description of this colourful bird ‘Because likewise they [the merchants] cannot bring the birds alive on their vessels from these lands. They skin them to bring the dead bodies … One cannot bring these birds alive to our shores’.[9]

In Belon’s woodcut we see the bird, looking very lively indeed, perching on a branch (an imaginary habitat). Belon’s name for the bird ‘Merle du bresil (‘blackbird of Brazil’), was not meant to indicate that that bird was black (tanagers are a combination of black and red), but that it had similar feeding habits to European blackbirds. His inclusion of an image of the Brazilian tanager was not only of ornithological interest – it also pointed to French colonial ambitions in the New World, for it had been brought to Europe from the France Antarctique (Guanabara Bay in Rio de Janeiro), where, for a short time (1555–67), the French crown had attempted to colonize the region, intent as it was on developing a new source of red dye, the trade of which had been disrupted by the fall of Constantinople in 1453.[10] As Kleiter notes, the Brazilian tanager ‘became a convenient metonymy for Brazil, because it could represent a place of origin, its commodity, the resulting products, and their attendant wealth’.[11]

Dominique Crowley: Monstrorum, RHA Ashford Gallery

Dominique Crowley, Memento IV, 2024, oil and acrylic resin on wood panel, 40cm x 40cm. Blue-grey Tanager. © Dominique Crowley 2024, image courtesy of the artist.

The Italian natural historian Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), who was particularly interested in depicting the strange birds from the New World was clearly influenced by Belon’s work, for he likewise included the Brazilian tanager among blackbirds in his own three-volume work on birds. Alongside it he also included a strange version without feet, and named the chapter ‘De Merula Apode Indica’ (literally ‘On the Indian footless blackbird’), because he was unsure if it was the same bird as that described by Belon. He noted that he had been sent a dead specimen by Franciscus Malocchius, who was in charge of the Pisan garden of Ferdinando I de’ Medici (1549–1609), Grand Duke of Tuscany.[12] Aldrovandi certainly had doubts about the bird being footless, and although he name checked another reputedly footless bird, the famous bird of paradise, he noted that Aristotle (384–322 BC), had stated that all animals had four limbs (and hence deduced that he might simply be missing the bird’s two legs).[13]

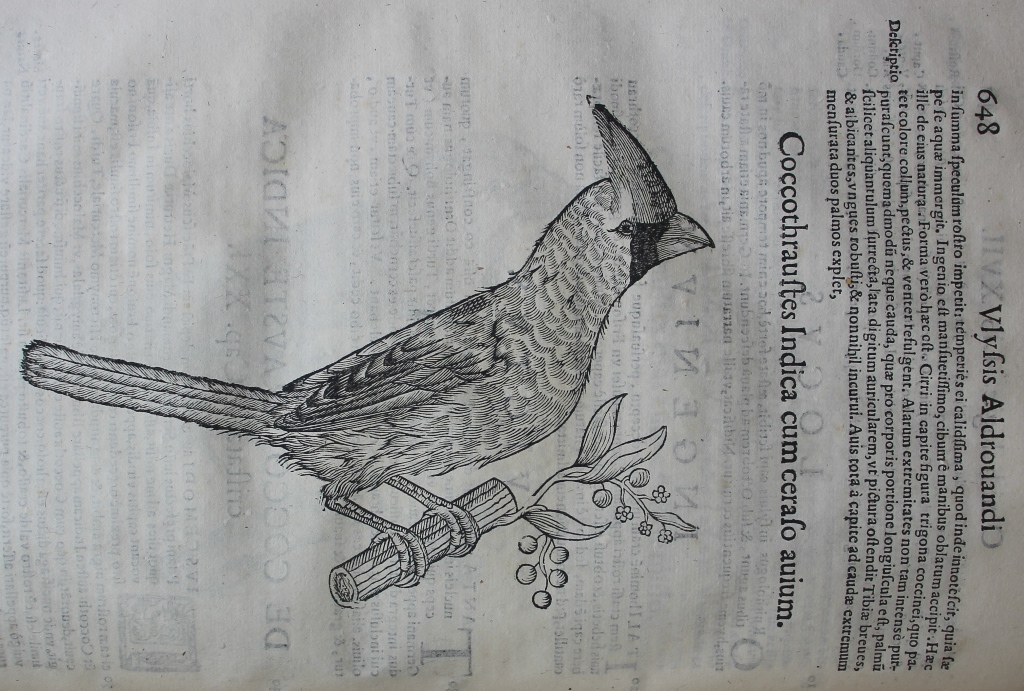

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637), ii, p. 648: Northern Cardinal.

While Aldrovandi might have owed his main tanager image to Belon, he also included a number of woodcuts which in some cases proved to be the first ever image of that particular bird from the Americas. This image of a northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis), is one of them. It first appeared in the 1599 edition and the woodcut was reused in Worth’s copy of Aldrovandi’s Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46). Its name derives from its vibrant red colour which resembled the red clothes of a cardinal (indeed the bird is also known as the ‘red cardinal’). It is likely that Aldrovandi’s bird came from Mexico, rather than Virginia (where the ‘red cardinal’ is now the state bird), for we know that cardinals from Mexico soon became popular cage birds in sixteenth-century Europe.[14]

As the image shows, Aldrovandi gave the bird the name ‘Coccothrautes Indica cum ceraso auium’ and explained both his naming of the bird and the provenance of the image as follows:

A bird of this sort, pictured in the guise of life, was sent to me several days ago on the command of his serene highness, Ferdinand, Duke of Etruria, by the superintendent of his garden at Pisa, F. Franciscus Malocchius, who is in sending it affirmed that in his native land – an island, to be sure, which he called Cape Verde – it is commonly named fruson, a name resembling frison, the species described in our next preceding chapter, to which even in beak it is like: a black patch, however, surrounds the beak, and according to Girolamo Mercuriale, it is the size of a thrush. It has, therefore, seemed good to me to name it Coccothraustes Indica. It eagerly devours almonds, so Malocchius tells me (and in this respect also it corresponds to the Coccothraustes, which breaks fruit of this sort with its beak and is on that account called ‘the nutcracker’), and other seeds, and even small bones. In order to do this equally well, this bird, like ours, is provided with a strong, thick, and sturdy beak. Lusitanis Mercurialis asserts that it is commonly called cardinalitus, perhaps because it is red; it seems to wear a red hood.

Concerning its nature and its habits Malocchius told me these things: It imitates the voices of other birds, particularly that of the nightingale; it feeds eagerly, and devours almonds and chickweed (alsinem herbam); seeing its own image in a mirror, it becomes pitifully agitated, uttering whistles, lowering its crest, raising its tail like a peacock, fluttering its wings, and at length striking the mirror with its beak. Its body temperature is high, as would seem, for it often plunges itself into water. In disposition it is quite tame, and will take food from an extended hand. So much concerning its nature.

As to its form – The triangular crest upon its head is crimson, and this colour spreads down the neck and glows from breast and belly. The tips of the wings are not so intensely reddened, or perhaps not at all; the tail, which proportionately to the body is rather long, is straight, about one palm in length and a finger’s breath, as the picture shows it to be. The tibiae are short and whitish; the claws strong and not at all hooked. The total length of the bird from the bead to the tip of the tail is two palms.[15]

Northern Cardinal, Cardinalis cardinalis (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1890.63.1. © NMI

Malocchius’s testimony that the cardinal was native to Cape Verde is curious, for their habitat is Central and Northern America. As Johnston notes, ‘Today, its range extends from southern Canada through the eastern and central United States, southward through parts of Mexico and Belize’.[16] This was not the only error in Aldrovandi’s commentary for Girolamo Mercuriale (1530–1606), who was also cited by Willughby and Ray in 1678, had not actually commented on the red cardinal. Willughby’s and Ray’s red cardinal was neither from Cape Verde nor Mexico: They note that it was ‘brought into England out of Virginia; whence, and from its rare singing, it is called, The Virginian Nightingale’.[17] As Johnston notes, their image was that of Aldrovandi’s in reverse and minus the cherries.[18]

Francisco Hernández, Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia a Francisco Hernández … primum compilata, dein a Nardo Antonio Reccho in volumen digesta, a Io. Terentio, Io. Fabre, et Fabio, Columna Lynceis notis, & additionibus longe doctissimis illustrata. Cui demum accessere, aliquot ex principis Federici Caesii frontispiciis Theatri naturalis phytosophicae tabulae una cum quamplurimis iconibus ad octingentas, quibus singula contemplanda graphice exhibentur (Rome, 1651), p. 705: Hummingbird.

One of the most iconic birds mentioned by the Spanish physician Francisco Hernández (1517–87), in his Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia a Francisco Hernández, which Worth owned in the 1651 edition, was the hummingbird. This bird, along with the quetzal (which he describes in the same chapter), were vital for Mesoamerican rituals.[19] As Hernández Urraca notes, the hummingbird could only be found in the Americas and 57 of the 330 species of hummingbird in the Americas were visible in Mexico.[20] In Mayan legends they were considered to be messengers from the gods.[21] Aztecs associated them with their god of war, Huitzilopochtli, whose name, as Hernández Urraca notes, was a combination of two Nahuatl words: ‘huitzilli’ (hummingbird) and ‘opochtli’ (left).[22]

Hummingbirds were said to be the embodiment of souls who had died in battle (or who had been sacrificed).[23] Their flesh was also reputed to be of medicinal benefit so it is no surprise to find Francisco Hernández commenting on hummingbirds since his principal mission was to track down new medicinal cures in Mexico.[24] It is clear, however, that his interests transcended solely medical uses – indeed he noted that ‘it is not our purpose to account only for medicaments, but to gather the flora and compose the history of the natural things of the New World, laying out in front of the eyes of our lord Philip and our fellow countrymen all the things produced in this New Spain’.[25]

The hummingbird was also described by the Incan Garcilaso de la Vega (1539–1616), in his Royal Chronicles, which Worth owned in a French 1633 Parisian edition. In this work, in which Garcilaso discussed birds found in Peru, he notes that while the Spaniards called it tominejo, it was called quenti by the Incas.[26] Carolus Clusius (1526–1609), who never had the opportunity to travel to the New World, was eager to include an example of an ourissia (a kind of hummingbird), for he had been sent an image of one by Jacques Plateau.[27] While he discounted some of the information about the bird sent to him by Plateau, he was keen to draw attention to the song of the hummingbird.[28] Clusius, typically, produced a more accurate account of the bird than that of Willem Piso (1611–78), who discusses what he calls the guainumbí (hummingbird), in De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658). In it he produced a rather fanciful account of the genesis of a hummingbird, arguing that it evolved from a caterpillar.[29] This was not the only fanciful account of the generation of the hummingbird emanating from Brazil: the Portuguese Jesuit Fernāo Cardim (c. 1548–1625), in his treatise on Brazil, suggested that while some hummingbirds hatched from eggs, other arose from ‘bubbles’.[30]

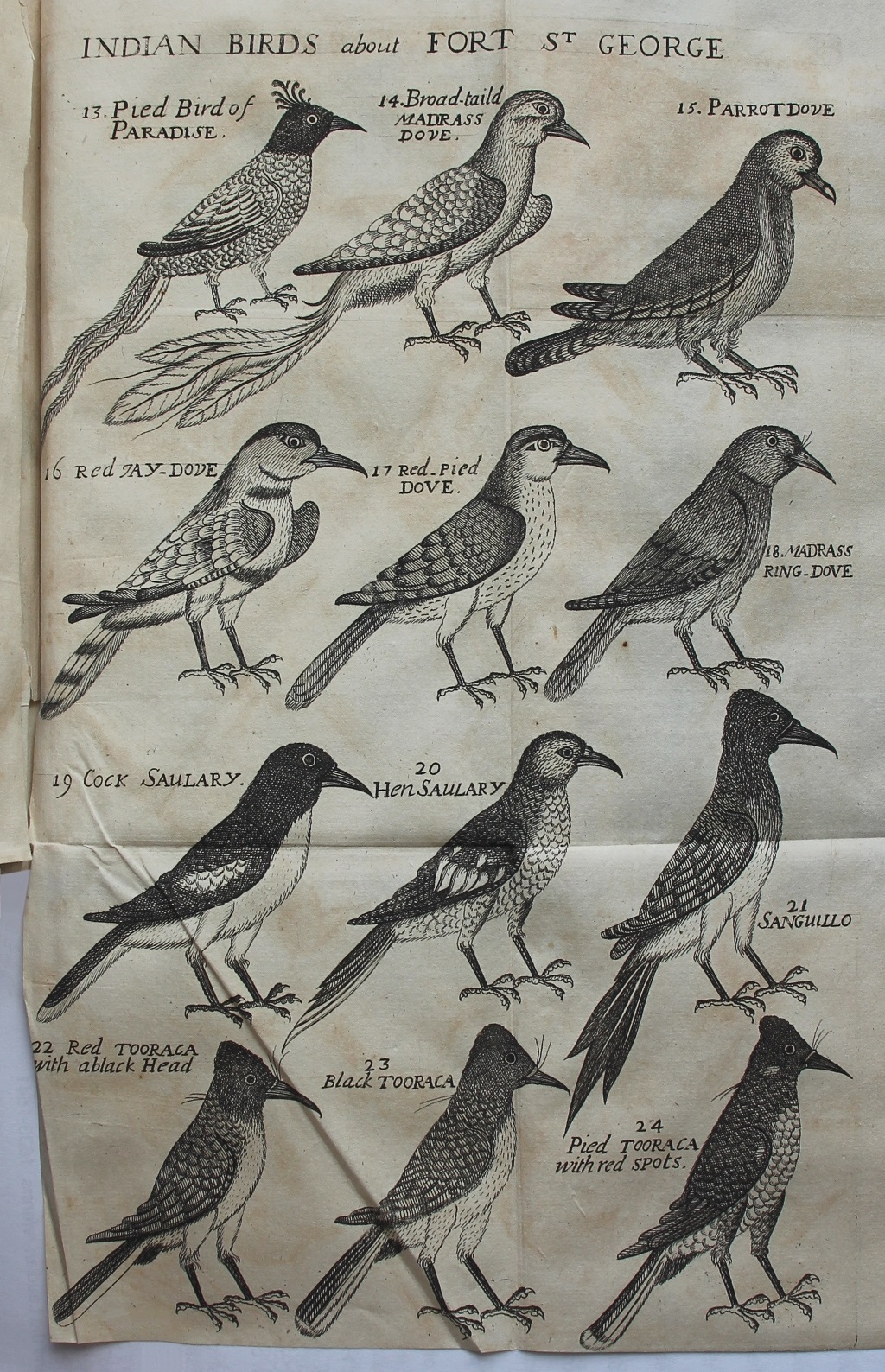

John Ray, Synopsis methodica avium & piscium; Opus Posthumum, quod Vivus recensuit & perfecit ipse insignissimus author: in quo multas species, in ipsius Ornithologiâ & Ichthyologia desideratas, adjecit: Methodumque suam Piscium Naturæ magìs convenientem reddidir. Cum apendice, & iconibus (London, 1713), plate 2: Indian birds about Fort St George.

Just as John Ray (1627–1705) had incorporated botanical information from Hernández’s researches in Mexico into his Historia plantarum (1686–1704), which Worth had included in his magnificent botanical collection, so too did some of Hernández’s comments on birds in the Americas find their way into Willughby and Ray’s Ornithology … (London, 1678).[31] These were not only located in the appendix to the 1678 English translation, which was entitled ‘An Appendix to the history of birds, containing such birds as we suspect for fabulous, or such as are too briefly and unaccurately described to give us a full and sufficient knowledge of them, taken out of Franc. Hernadez especially’, but might also be found in the text.

As the above image demonstrates, Ray was also receiving information about birds from India, for he provided his readers with two plates of birds from Fort St George, in Madras, now Chennai, the largest city in Tamil Nadu in southern India. He had received these illustrations from James Petiver (c. 1663–1718), the London apothecary, natural historian and fellow of the Royal Society, whose Gazophylacii naturæ & artis : decas prima-[quinta] (London, 1702), was also collected by Worth. Petiver, who sometimes acted as an assistant to both Ray and Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753) in turn had sourced them from Edward Bulkley, a surgeon in Madras.[32] As Winterbottom has shown, Bulkley and his predecessor Samuel Browne (d. 1698), had been responsible for sharing a great deal of information about the plants (and in this case birds), with Petiver, who in turn had passed it on to nodes in his extensive scholarly friendship networks.[33] Bulkley had joined Browne at Fort St George in 1692, succeeded him in his post in 1697, and had remained at Madras until 1709, just four years before his own death in 1713.[34] The above image is the second plate, while the first plate included images of a ‘Pied Wag-tail’; a ‘Partridge Snipe’; a ‘Reg-legged Crane’; a ‘Madras Rail Hen’; a ‘Madras Sea-Crow’; a ‘Forked Wag-tail’; a ‘Mottled Jay’; a ‘Yellow Jay’; a ‘Buff Jay’; a ‘Madras Jay’; a ‘Small Blue Jay’; and a ‘Green Jay’.

Fort St George was of strategic important to the East India Company and the two surgeons, Browne and Bulkley, played an important political as well as medical role.[35] Back in England Petiver publicised their findings in natural history and it is clear that the plates of birds from Madras came to Ray from Bulkley, who in turn was, as Winterbottom notes, dependent on the work of local artists.[36] The ‘Icones Avium Maderaspatanarum’, a coloured version of the above plate, is now British Library Additional Manuscript 5266. 24 images were included in two plates in Ray’s posthumously published book on birds and fish: Synopsis methodica avium & piscium (London, 1713). These images of birds from Madras, with accompanying descriptions sent by Bulkley, were the first to be depicted in a European text.[37]

Dominique Crowley: Monstrorum, RHA Ashford Gallery

Dominique Crowley, Memento III, 2024, oil and acrylic resin on wood panel, 40cm x 40cm. Birds: Black throated Mango, Island Canary, Sparkling Violetear. © Dominique Crowley 2024, image courtesy of the artist.

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Ali, Salim, Bird study in India: its history and its importance (New Delhi, 1979).

Anon., ‘Hummingbirds and the afterlife’, online blog from Dumbarton Oaks.

Asúa, Miguel de, and Roger French, A New World of Animals: Early Modern Europeans on the Creatures of Iberian America (Aldershot, 2005).

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Coulton, Richard, ‘‘What he hath gather’d together shall not be lost’: Remembering James Petiver’, Notes and Records, 74 (2020), 189–211.

Hernández, Francisco, Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia a Francisco Hernández … primum compilata, dein a Nardo Antonio Reccho in volumen digesta, a Io. Terentio, Io. Fabre, et Fabio, Columna Lynceis notis, & additionibus longe doctissimis illustrata. Cui demum accessere, aliquot ex principis Federici Caesii frontispiciis Theatri naturalis phytosophicae tabulae una cum quamplurimis iconibus ad octingentas, quibus singula contemplanda graphice exhibentur (Rome, 1651).

Hernández Urraca, Vanessa, ‘The Hummingbird in Mexican culture’, online blog from the Association of Avian Veterinarians (2022).

Johnston, David W., ‘The earliest illustrations and description of the Cardinal’, Banisteria, 24 (2004), 1–7.

Kleiter, Christine, ‘Birds, Colour, and Feet: A “Naïf Portrait” of the Brazilian Tanager in Pierre Belon’s L’Histoire de la Nature des Oyseaux’, Journal of the LUCAS Graduate Conference, 8 (2020), 6–29.

Norton, Marcy, ‘The Quetzal takes flight: microhistory, Mesoamerican knowledge, and early modern natural history’, in Arredondo, Jaime Marroquín, and Ralph Bauer (eds), Translating Nature: Cross-Cultural Histories of Early Modern Science (Pennsylvania, 2019), pp 119–47.

Smith, Paul J., ‘On toucans and hornbills: readings in early modern ornithology from Belon to Buffon’, in Enenkel, Karl A. E., and Mark S. Smith (eds), Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts (Leiden, 2007), pp 75–119.

Swan, Claudia, ‘Exotica on the Move: Birds of Paradise in Early Modern Holland’, Art History, 38, no. 4 (2015), 620–35.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

Winterbottom, Anna, ‘Botanical and medical networks: Madras through the collections of two EIC surgeons’, in Winterbottom, Anna, Hybrid knowledge in the early East India Company World (Basingstoke, 2016), pp 112–39.

__

[1] Swan, Claudia, ‘Exotica on the Move: Birds of Paradise in Early Modern Holland’, Art History, 38, no. 4 (2015), 626.

[2] Smith, Paul J., ‘On toucans and hornbills: readings in early modern ornithology from Belon to Buffon’, in Enenkel, Karl A. E., and Mark S. Smith (eds), Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts (Leiden, 2007), p. 78.

[3] Asúa, Miguel de, and Roger French, A New World of Animals: Early Modern Europeans on the Creatures of Iberian America (Aldershot, 2005), p. 189.

[4] Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 319.

[5] Kleiter, Christine, ‘Birds, Colour, and Feet: A “Naïf Portrait” of the Brazilian Tanager in Pierre Belon’s L’Histoire de la Nature des Oyseaux’, Journal of the LUCAS Graduate Conference, 8 (2020), 14.

[6] Translated in ibid., 19.

[7] Ibid., 10.

[8] Ibid., 17.

[9] Ibid., 14.

[10] Ibid., 18.

[11] Ibid., 20.

[12] Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637), ii, p. 629.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Johnston, David W., ‘The earliest illustrations and description of the Cardinal’, Banisteria, 24 (2004), 3.

[15] Translation by Christy quoted in ibid., 3–4.

[16] Ibid., 3.

[17] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 245. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[18] Johnston, ‘The earliest illustrations and description of the Cardinal’, 5.

[19] On this see Norton, Marcy, ‘The Quetzal takes flight: microhistory, Mesoamerican knowledge, and early modern natural history’, in Arredondo, Jaime Marroquín, and Ralph Bauer (eds), Translating Nature: Cross-Cultural Histories of Early Modern Science (Pennsylvania, 2019), pp 119–47.

[20] Hernández Urraca, Vanessa, ‘The Hummingbird in Mexican culture’, online blog from the Association of Avian Veterinarians (2022).

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Anon., ‘Hummingbirds and the afterlife’, online blog from Dumbarton Oaks.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Quoted in Asúa and French, A New World of Animals: Early Modern Europeans on the Creatures of Iberian America, pp 102–3.

[26] Ibid., p. 50.

[27] Ibid., p. 111.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid., p. 122.

[30] Ibid., p. 146. Worth did not collect Cardim’s treatise.

[31] Ibid., p. 119.

[32] On Petiver’s links with Ray and more generally his extensive correspondence network see Coulton, Richard, ‘‘What he hath gather’d together shall not be lost’: Remembering James Petiver’, Notes and Records, 74 (2020), 189–211.

[33] On this see Winterbottom, Anna, ‘Botanical and medical networks: Madras through the collections of two EIC surgeons’, in Winterbottom, Anna, Hybrid knowledge in the early East India Company World (Basingstoke, 2016), pp 112–39.

[34] Ibid., p. 113.

[35] Ibid., p. 116.

[36] Ibid., p. 128.

[37] Ali, Salim, Bird study in India: its history and its importance (New Delhi, 1979), p. 28.