Hoopoes and Hornbills

Hoopoes have enthralled us for millennia. Their distinctive crest may be found lurking on more than one tomb of ancient Egypt. The earliest image located to date was on the mortuary temple of Userkaf (2494–2487 BC), the first ruler of the fifth dynasty, and they continued to be depicted on tomb wall-paintings in ancient Egypt.[1] One reason for their popularity was because they were thought to be connected to Horus, son of Isis and Osiris, who is sometimes depicted holding a hoopoe in his hand in statutes of the god as a child.[2]

Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 293: Hoopoe.

The hoopoe, called in Greek ‘Epopa’ and in Latin ‘Upupa’ due to its distinctive call was evidently well known to the French natural historian Pierre Belon (1517–64), for he suggests that it hardly needs to be described.[3] He does, however, comment on its fairly large feet, short legs and black tail, composed of twelve feathers marked with white.[4] Its wings were significantly more colourful, combining brown, black, white and ash-grey and this was set off by its fawn-coloured head, with some black mixed in it.[5] Like all commentators on hoopoes, Belon drew attention to the hoopoe’s colourful crest which he said was made up of about twenty long feathers.[6] From this level of detail it is clear that Belon was describing a bird he had examined in detail but he adds ruefully that despite having had a chance to examine the bird little was known about its characteristic crest.[7]

Hoopoe; Bull Island, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Hoopoes certainly made a comeback in Britain and Ireland in Spring 2025! They are generally distributed throughout Europe, North Africa and Asia but usually they don’t make it this far north in large numbers. That changed in March 2025 where there was a host of hoopoe sightings, primarily in the south of the country.[8] Bird watchers were treated to a real feast and were able to see hoopoes on multiple occasions and verify for themselves the description of them in that ‘bible’ of bird watching, Collins Bird Guide:

One of the most striking and distinctive birds of the whole region: buffy-pink with black- and white-striped, broadly rounded wings, and crown with an erectile crest like an Indian chief’s (though normally raised momentarily on landing, otherwise rarely).[9]

As Jones noted, the hoopoes who had made it to our shores were Eurasian hoopoes (Upupa epops), rather than African hoopoes (Upupa africana).[10]

It is interesting to compare Derek O’Reilly’s image with Willughby and Ray’s detailed description in Ornithologia (London, 1676):

Its Bill is two inches and an half long, black, sharp, and something bending. The Tongue small, as Aldrovandus rightly hath it, deep withdrawn in the mouth, triangular, being broad at bottom, and sharp at top, like a perfect equilateral triangle. The shape of the body approacheth to that of a Plover. The Head is adorned with a most beautiful Crest, two inches high, consisting of a double row of feathers, reaching from the Bill to the nape of the Neck, all along the top of the Head: Which it can at pleasure set up, and let fall. It is made up of twenty four or twenty six feathers, some of which are longer than others; the tips of them are black; under the black they are white, the remaining part under the white being of a Chesnut, inclining to yellow. The Neck is of a pale red: The Breast white, variegated with black strokes tending downward. The older birds had no black strokes in their Breasts, but only in their sides. The Tail is four inches and an half long: [Aldrovandus saith six] made up of ten feathers only, black, with a cross mark or bed of white of the figure of a Crescent or Parabola, the middle being toward the Rump, the horns toward the ends of the feathers. The Tail is extended further than the Wings complicated. There are in each Wing eighteen quils or master-feathers, of which the ten foremost are black, having a white cross bar, which in the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh is more than half an inch broad. The seven following feathers have four or five white cross bars. The limbs or borders of the last are something red: The Rump is white. The long feathers springing out of the shoulders and covering the back are varied with white and black cross lines or bars, after the same manner as the Wings.[11]

Conrad Gessner, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), Book III, p. 703. Hoopoe.

Belon’s contemporary, the Swiss natural historian Conrad Gessner (1516–65), provided his readers with a lengthy account of the bird, commenting on its name, and reminding his readers that the hoopoe had even made it into the Old Testament where they were listed as ‘unclean birds’.[12] Gessner was keen to provide citations from ancient authorities such as Pliny the Elder (23/24–79), but also gave his views on the hoopoes’s call, the food they preferred, their habitats, and how they had previously been classified.[13] He also included comments by the third century Roman author Aelian who had noted that Egyptians honoured the hoopoe due to the example hoopoes gave of filial piety.[14]

As Kunstmann has noted, as a result the hoopoe had for centuries been a symbol of love of parents.[15] Indeed, the hoopoe has been a familiar figure in folklore: a hoopoe was said to have received his crest from King Solomon – and in Surah 27 he is portrayed as acting as an intermediary between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.[16] Medicinal and magical powers were also attributed to hoopoes.[17] However, not all of the commentary about hoopoes was positive for often they were connected with dirt and talked about as the bird that fouled its own nest.[18] Yet, as Attia notes, this may be due to a misunderstanding for during breeding season female hoopoes secrete a noxious smelling substance in order to guard their eggs from infection.[19] Aristotle had suggested something similar – though in his case he surmised that hoopoes smeared their nests with human dung in order to ward off humans![20]

Walter Charleton, Onomasticon zoicon, plerorumque animalium differentias & nomina propria pluribus linguis exponens. Cui accedunt mantissa anatomica; et quædam de variis fossilium generibus. Autore Gualtero Charletono, M.D. Caroli II. Magnæ Britanniæ Regis, medico ordinario, & Collegii Medicorum Londinensium Socio (London, 1668), plate between pp 92 and [93]. Hoopoe.

This image of a hoopoe comes from Onomasticon zoicon (London, 1668), by the English physician and natural philosopher Walter Charleton (1620–1707). As Mullens argues, though Charleton’s section on birds in Onomasticon zoicon was soon overshadowed by the seminal Ornithologia (London, 1676), of Francis Willughby (1635–72) and John Ray (1627–1705), it is more than the mere listing of bird names it is sometimes characterised to be.[21] For this charming image of a hoopoe alone it should receive greater acclaim than it has heretofore but given Charleton’s massive output, his Onomasticon zoicon is too easily overlooked. Not by Worth however, who duly added it to his collection! Charleton might not tell us much about birds but he did note that hoopoes were rarely to be seen in England.[22] The above plate was based on a hoopoe which had been killed near London and sent to him and which he duly added to this text precisely because the bird was so rarely seen in England.[23] Charleton tells us that his hoopoe, called in German ‘ein Widhopff’ was about the size of a thrush and that it had black and white feathers and an identifiable crest which from the top of its beak all the way back to the back of its head, which could be raised and lowered, depending on the bird’s mood![24]

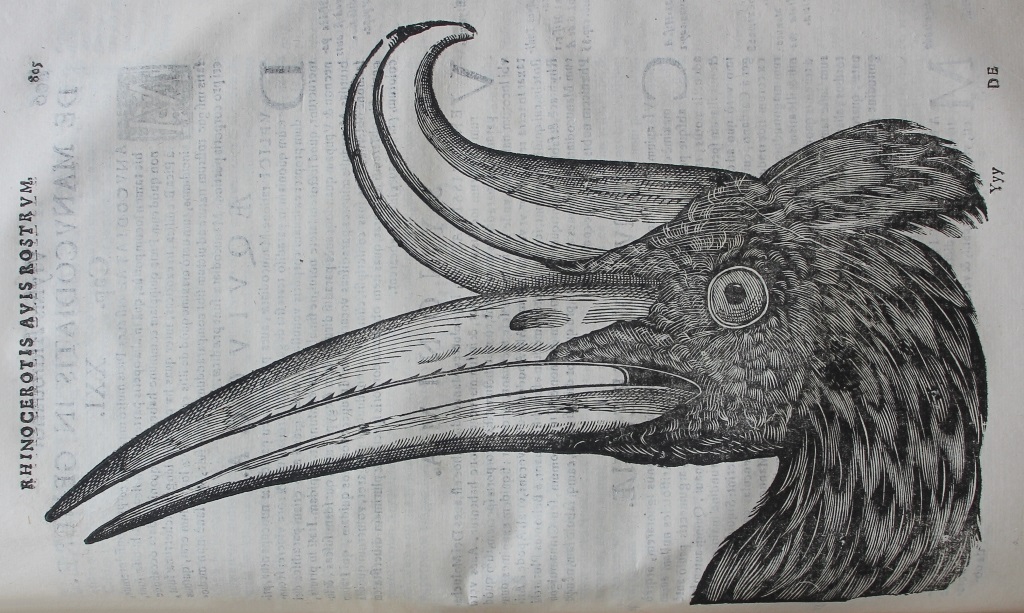

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1646), i, p. 805: Hornbill.

Though hoopoes and hornbill look decidedly different they are both members of the order Bucerotiformes. In the early modern period it was common to conflate hornbills and exotic birds such as toucans for they both had extraordinary bills but while toucans could only be found in the tropical forests of the New World, hornbills were creatures of the Old World.[25] While toucans had become known from the early 1520s onwards, hornbills had to wait until the Italian natural historian Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605) decided to include this striking image of a hornbill in his magnum opus. Aldrovandi clearly thought toucans and hornbills were linked as he includes this image of a hornbill directly after his toucan image. As the caption ‘Rhinocerotis avis rostrum’ makes clear, Aldrovandi was not quite sure what to make of it and grasped at classical allusions in Pliny the Elder, and the fourth-century writer Claudianus for clues.

Willughby and Ray in Ornithologia (London, 1676), summarized Aldrovandi’s comments on the hornbill as follows:

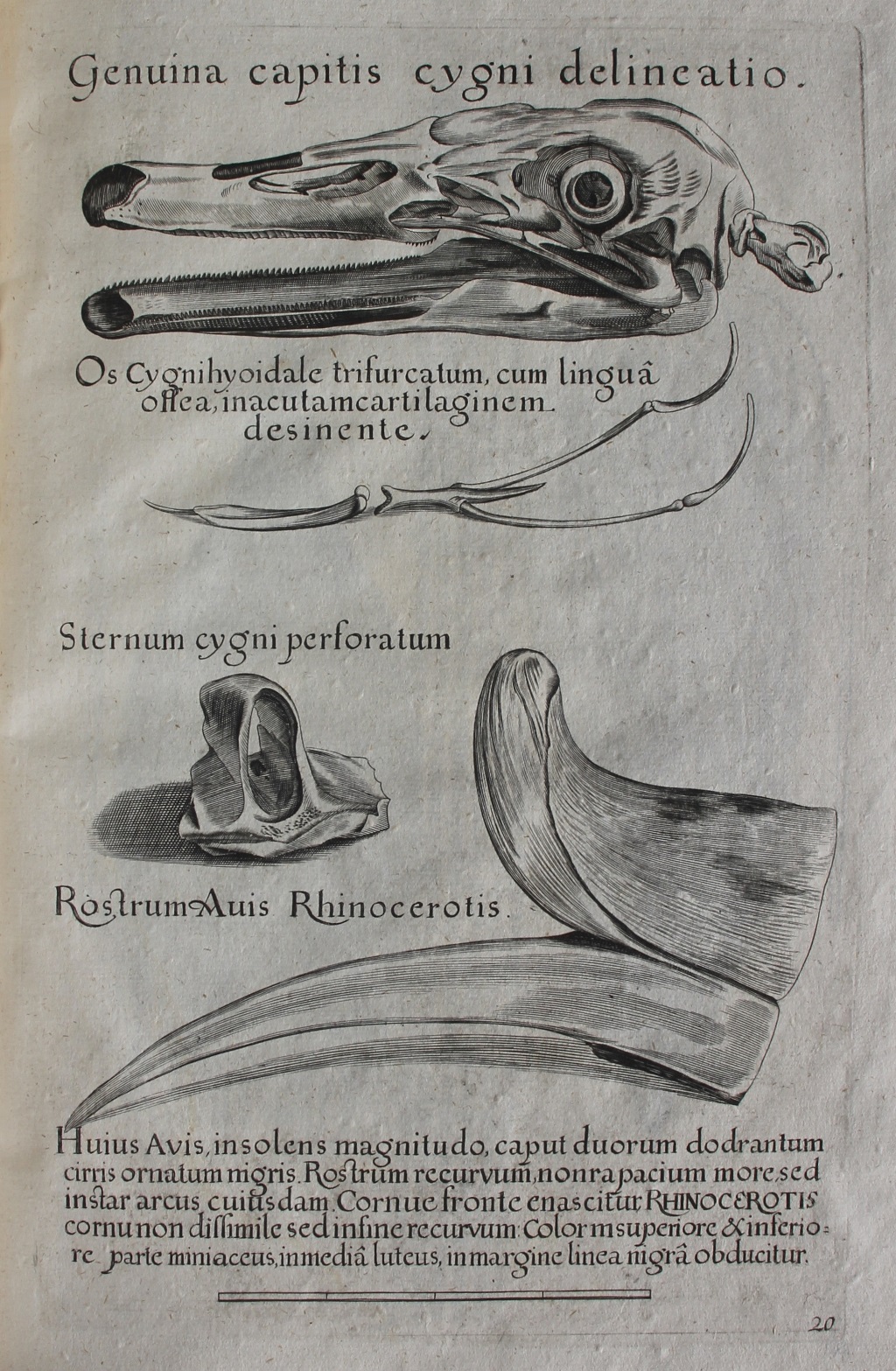

Aldrovandus describes the Bill thus: It is almost twenty eight inches long, crooked, not after the manner of rapacious birds, but like a Bow. All the lower part is of a pale or whitish yellow, the upper part toward the Head of a red or Vermilion, else of the same colour with the lower. The upper Mandible only within is serrate or dented after the manner of the Toucan. The horn springs out of the forehead, and grows to the upper part of the Bill, being of a great bulk, so that near the forehead it is a Palm broad; not unlike the Rhinocerots horn, but crooked at the tip: The colour both in the upper and lower part is Vermilion, in the middle yellow. If the rest of the parts of the body are answerable to the Head; I am of Cardans and Plinies opinion, that this Bird is bigger than an Eagle.[26]

Aldrovandi’s image displays the bill of Rhinoceros Hornbill (Buceros rhinoceros), and Smith argues that it was in fact the bill of a hornbill from Borneo.[27]

Rhinoceros Hornbill, Buceros rhinoceros (Linnaeus, 1758). © Paolo Viscardi

As Aldrovandi explains, his image was not drawn from life but rather was based on an image he had been sent of a bird said to have been killed during the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.[28] As he ruefully noted, ‘once they have found this bird, others will be able to treat all this more precisely, and to verify our conjecture’.[29] The bill of Rhinoceros Hornbill was included in the first edition of Aldrovandi’s three-volumes on birds (1599–1603), and within two years European readers were offered more information about the hornbill by the Flemish physician and botanist Carolus Clusius (1526–1609), in his Exoticorum libri decem (Antwerp, 1605), a fascinating study of all things exotic, which Edward Worth (1676–1733), duly acquired.

Michael Rupertus Besler, Gazophylacium rerum naturalium: e regno vegetabili, animali & minerali depromptarum, nunquam hactenus in lucem editarum, cum figuris aeneis ad vivum incisis, opera Michaelis Ruperti Besleri (Leipzig and Frankfurt, 1716), plate 20: The skull of a swan and a hornbill.

As Smith notes, Clusius’s hornbill was a different species (a Southern Ground Hornbill from Africa), which he had been sent by Jacques Plateau, a collector of curiosities in Tournai.[30] It was actually more unusual to find a hornbill in an early modern collection than a toucan and in the decades after Aldrovandi and Clusius confusion reigned. The Dutch physician Willem Piso (1611–78) and the German polymath Georg Marcgraf (1610–c. 1643/4), in their ground-breaking natural history of Brazil, Historia Naturalis Brasiliae (1648), had provided a description which was subsequently adopted by Willughby and Ray in their attempt to describe what they called ‘The horned Indian Raven or Topau, called the Rhinocerot Bird’:

This horned Bird as it casts a strong smell, so it hath a foul look, much exceeding the European Raven in bigness. It hath a thick Head and Neck, great Eyes; the Bill but moderate in respect of the body: The longer and more acuminate part bending downward argues the Bill to be made and designed for rapine: But the upper part, which is shorter, thicker, and bending upward doth resemble a true Horn, both to the sight and touch: The one moity whereof, viz. that toward the Head, is contiguous to the Bill, so that both together after the same manner grow to [or rather spring out of] the end of the Head: The other moity is separate from the Bill, bending the contrary way, viz. upwards, so that they seem to be like the forked tail of a Fish. It lives upon Carrion and Garbage, i. e. the carkasses and Entrails of Animal.[31]

As Smith notes, this description by Piso and Marcgraf remained influential for a long time.[32]

However, even Piso and Marcgarf were unsure of what they were dealing with:

I have also a very light and very large bird’s bill, which has on the upper part a prominent horn emanating from the upper part of the bill, and which is hollow and red-coloured, especially at the bill. I do not know if this bill comes from Brazil or from the East Indies. Those who have been in Brazil cannot remember having seen it, whereas the toucan is a very common bird there.[33]

Worth would have been well aware of these doubts as he owned a copy of Piso’s De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim. Quorum contenta pagina sequens exhibit (Amsterdam, 1658), which combined Historia Naturalis Brasiliae with material from the Dutch East Indies by Jacob de Bondt (1592–1631).[34] However, though Willughby and Ray put toucans and hornbills together in their chapter on ‘Birds of the Crow-kind’, but they did, at least, differentiate between them. And, most importantly, they had access to actual specimens, noting that they had seen three varieties ‘all which we have caused to be engraven and exhibited to the Readers view’.[35]

Rhinoceros Hornbill, Buceros rhinoceros (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:2003.52.264. © NMI

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Attia, Venice Ibrahim, ‘Hoopoe in Ancient Egypt’ (2018).

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

BirdWatch Ireland report on hoopoes in Ireland in Spring 2025: ‘March migrations: Rare birds and returning migrants’, 31 March 2025.

Charleton, Walter, Onomasticon zoicon, plerorumque animalium differentias & nomina propria pluribus linguis exponens. Cui accedunt mantissa anatomica; et quædam de variis fossilium generibus. Autore Gualtero Charletono, M.D. Caroli II. Magnæ Britanniæ Regis, medico ordinario, & Collegii Medicorum Londinensium Socio (London, 1668).

Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617).

Jones, Calvin, ‘Unprecedented Eurasian Hoopoe influx into Ireland’, Ireland’s Wildlife, 10 April 2025.

Kunstmann, John Gotthold, The Hoopoe: A study in European folklore (Chicago, 1938).

Mullens, W. H., ‘Walter Charleton and the “Onomasticon Zoicon”’, British Birds, 5, no. 3 (1911), 64–71.

Smith, Paul J., ‘On toucans and hornbills: readings in early modern ornithology from Belon to Buffon’, in Enenkel, Karl A. E., and Mark S. Smith (eds), Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts (Leiden, 2007), pp 75–119.

Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022).

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Attia, Venice Ibrahim, ‘Hoopoe in Ancient Egypt’ (2018), 7.

[2] Ibid., 9.

[3] Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 293.

[4] Ibid., p. 294.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] BirdWatch Ireland, ‘March migrations: rare birds and returning migrants’, 31 March 2025, reported that most sightings were in Wexford, Waterford, Kilkenny and Cork, though they were spotted as far north as Co. Down.

[9] Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed (London, 2022), p. 248.

[10] Jones, Calvin, ‘Unprecedented Eurasian Hoopoe influx into Ireland’, Ireland’s Wildlife, 10 April 2025.

[11] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 145. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[12] Leviticus 11: 19 and Deuteronomy 14: 18.

[13] Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), Book III, p. 705.

[14] Ibid. See also Attia, ‘Hoopoe in Ancient Egypt’ (2018), 11.

[15] Kunstmann, John Gotthold, The Hoopoe: A study in European folklore (Chicago, 1938), p. 22.

[16] Ibid., p. 7.

[17] Ibid., p. 11.

[18] Ibid., pp 42; 62.

[19] Attia, ‘Hoopoe in Ancient Egypt’ (2018), 2.

[20] Kunstmann, The Hoopoe: A study in European folklore, p. 45.

[21] Mullens, W. H., ‘Walter Charleton and the “Onomasticon Zoicon”’, British Birds, 5, no. 3 (1911), 64.

[22] Charleton, Walter, Onomasticon zoicon, plerorumque animalium differentias & nomina propria pluribus linguis exponens. Cui accedunt mantissa anatomica; et quædam de variis fossilium generibus. Autore Gualtero Charletono, M.D. Caroli II. Magnæ Britanniæ Regis, medico ordinario, & Collegii Medicorum Londinensium Socio (London, 1668), p. 92.

[23] Mullens, ‘Walter Charleton and the “Onomasticon Zoicon”’, 69.

[24] Charleton, Onomasticon zoicon, p. 92.

[25] Smith, Paul J., ‘On toucans and hornbills: readings in early modern ornithology from Belon to Buffon’, in Enenkel, Karl A. E., and Mark S. Smith (eds), Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts (Leiden, 2007), p. 76.

[26] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books, p. 127.

[27] Smith, ‘On toucans and hornbills: readings in early modern ornithology from Belon to Buffon’, p. 88.

[28] Ibid., p. 91.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid., p. 92.

[31] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books, p. 127.

[32] Smith, ‘On toucans and hornbills: readings in early modern ornithology from Belon to Buffon’, p. 98.

[33] Translation from Smith, ‘On toucans and hornbills: readings in early modern ornithology from Belon to Buffon’, p. 96.

[34] This work is explored on our Flightless birds webpage.

[35] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books, p. 127.