Land Fowl

In their classification of birds, Francis Willughby (1635–72), and John Ray (1627–1705), had a very broad conception of the term ‘land-fowl’, declaring that ‘Birds in general may be divided into Terrestrial and Aquatic, or Land and Water-fowl’.[1] In this view, land fowl might include birds of prey, parrots, and a host of other species. Today the term ‘land fowl’ is used in a far more limited sense, and denotes large ground-feeding birds such as chickens, quails, turkeys, pheasants, peacocks, capercaillies and guinea fowl (among others).

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637), ii, p. 337: Guinea fowl.

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), included a relatively lengthy commentary on guinea fowl in his massive book dedicated to the study of chickens and hens (Book XIV of the second volume of Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I], which Edward Worth (1676–1733), owned in a Bologna edition of 1637). He did so because he argued that guinea fowl resembled chickens ‘in almost every detail except crest and spurs’.[2] Much of his description was not his own – a fact he readily acknowledged – but was based on a description in the Historia animalium of Conrad Gessner (1516–65), an even more massive encyclopaedic work on natural history which had first been printed in 1555 and which Edward Worth owned in a Frankfurt 1617 edition:

Since the Ornithologist describes them very exactly, I gladly follow his description. The Mauritanian rooster, he says, is a very beautiful bird similar to a pheasant in size and body, shape, beak, and feet, armed with a vertex of horn rising into a horny peak at the rear, but gently sloping in a front elevation. Nature seems to have desired to fit the bird in the lower part of the head with thee projecting flaps, joining one between the eye and ear and one in the middle of the front – all the same colour as the vertex – in such a way that the entire group of flaps is placed on the bird’s head in the same way the ducal cap rests on the head of the most illustrious Duke of Venice, if you turn his cap around, from to back. The lower part of the cap is wrinkled all around. Where it rises on the top of the neck to the occiput, some black hairs (not feathers) grow out erectly turned in the reverse direction. The eyes are entirely black and so are the eyelids, if you except a spot at the top and rear part of the upper lid of each eye. At the end of the head on both sides there is a certain callous flesh the colour of blood, which nature has folded back so that it may not hang forward like a wattle; it ends in an averted fold in two sharp processes free from the head. From this flesh arise two carunculae which clothe the nostrils as they pass around them and separate the head in the anterior part from the rest of the pallid beak. The lower edges of these carunculae are folded lightly back near the beak and also under each nostril.[3]

However, as Aldrovandi makes clear, the true author of this description was not Gessner, who had incorporated it into his Historia animalium, but the English physician John Caius (1510–73). As Funk has shown, it was not Caius’s only contribution to Gessner’s encyclopaedia for the two scholars were friends.[4] They had first met in 1544, when Caius was returning to England from a fruitful research trip to Italy.[5] Both were academics: Caius had studied medicine at the famous University of Padua and had subsequently gone on to teach there in the early 1540s. He would later become President of the College of Physicians and in 1557 would re-found Gonville and Caius College at Cambridge.[6] Gessner was also a physician and had been professor of Greek at Lausanne and would later teach at Zurich. Both men had a keen interest in Galen but were also fascinated by the natural world. Gessner was indebted to Caius for many images and comments, including both the image and description of the Guinea Fowl, Numida meleagris.[7]

Guinea Fowl, Numida meleagris (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1903.94.1. © NMI

Caius was an excellent observer and it is interesting to compare his description of the bird’s unique colouring with this image of a stuffed Guinea Fowl, Numida meleagris in the Natural History Museum in Dublin. Caius tells us that:

The bird is of an exquisite purple colour under the throat; it is indistinctly purple on the neck. On the rear of the body, to one who looks at the bird from the top as it is rising, it looks as if the creature is sprinkled here and there with black and white powder, finely crushed into a darkish colour, but not completely mixed. There are some white oval spots to be seen and some round ones over the entire body, smaller at the top, larger at the bottom and held together by intervals of lines. These appear in the natural composition of the feathers, as they crisscross in a slanting stroke through the upper part only of the body, not similarly below. You would perceive this not from the entire body alone, but from separate feathers plucked away from the bird. The upper feathers, with slant lines intersecting each other, or, if you prefer, make of some circles of black and white powder joined at the end as in honeycombs or in nets, embrace oval or round spots in dark spaces; the lower feathers do not have the same design. Both, however, are arranged in the same fashion. In some feathers they are joined in such a way that they make almost acute triangles; in others, so that they present an oval form. There are three or four lines of this sort among separate feathers, arranged so that the smaller ones are placed in the embrace of the larger. At the end of the wings and on the tail, the spots proceed lengthwise with equidistant straight lines.[8]

Caius also pointed to the close resemblance of both the male and female guinea fowl – the only distinguishing mark (in his eyes), being that the hen’s head was ‘entirely black’.[9] Exactly where he saw and heard the bird is unclear but he clearly heard it for he tells us that ‘Their call is a divided whistle not more sonorous nor louder than the call of the quail, but similar to the call of the partridge, except that it is more shrill and less clear’.[10] As Aldrovandi truthfully concluded, ‘All this comes from Caius’.[11] However, he too wished to add in his own comments, commenting that he would call it ‘a Meleager or Numidian chicken’, and disagreeing with Caius that the hen’s head was completely black.[12]

How did a ‘Numidian chicken’ make its way to Bologna? Aldrovandi, quoting the French natural historian Pierre Belon (1517–64), gives us a clue: ‘As many of the products which merchants bring to France from Guinea were at first unknown, hence these hens were familiar to none of us before navigation to that region began, but now they are prominent enough and common in the residences of rich men’.[13] Belon, commenting on their name, points to the important role played by trade routes in making such birds known in Europe:

We now see how the common name of guinea hen must be accepted. For if we consider Africa, we shall see that the appellation is fitting. Numidia and Guinea are regions of Africa; one is on the shores of Ocean; the other, on the shore of the Mediterranean. The ancient Romans preferred to sail out at Cadiz, although some times, but rarely, they sailed straight across the sea. On the other hand, the Portuguese and the Normans or other inhabitants of the shores of Mediterranean Africa frequent the shores of Guinea more than those of the strait of Cadiz. Therefore it is not surprising that guinea hens are more frequently found in France than in Italy. For ships from these regions more often sail to our shores than to Italy.[14]

Belon’s logic is rather convoluted and it is tempting to commiserate with Aldrovandi when he writes ‘I do not see by what arguments he makes them African or Numidian’![15]

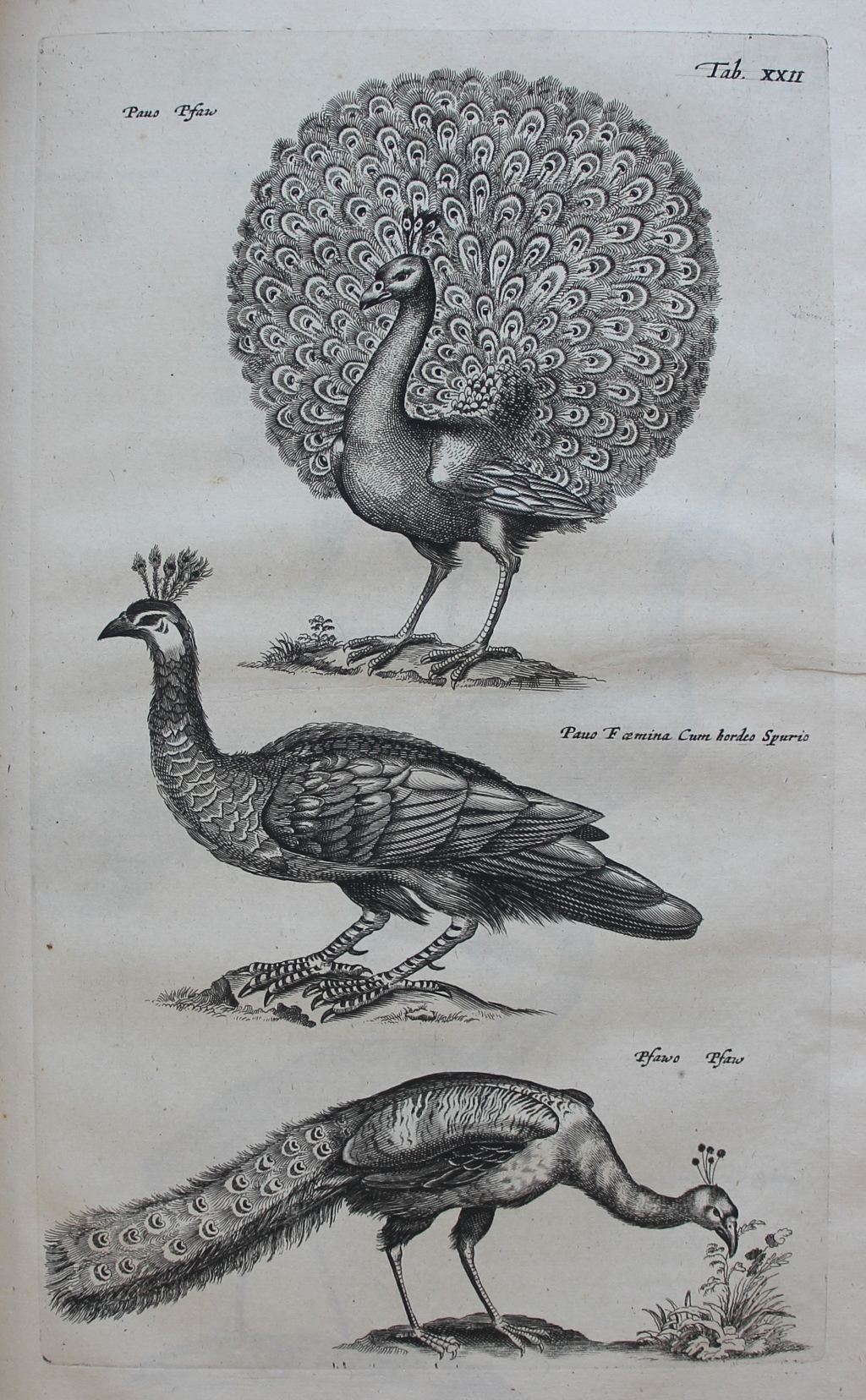

Joannes Jonstonus, Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri: cum aeneis figuris Johannes Jonstonus medicinae doctor concinnavit (Amsterdam, 1657), plate XXII: peacocks.

Joannes Jonstonus (1603–75), offers his readers his usual smorgasbord of information on peacocks, and, as usual is heavily dependent on Aldrovandi as a source:

Of old Peacocks were rare in Europe; when Alexander saw one in India, he forbad to kill it on pain of death; but afterwards in Athenaeus his time they grew so common, that they were as ordinary as Quails. In the Land Temistana, they lay sometimes 20 or 30 eggs, Martyr. They are so cleanly, that when they are young, they will die if they be wet; Albert. When they want cooling, they spread their wings, and bending them forward, they cover their bodies with them, and so drive off the force of heat: but if the wind blow on their back-parts, they will open their wings a little, and so are they cooled by the wind blowing between. They are said to know when any venomous medicament is prepared, and they will fly thither and cry. Aelian reports, that a Peacock will seek out the root of flax as a natural Amulet against Witchcraft, and will carry it thrust close under one of its wings. The Peacock suffers such languishing pains as children are wont to suffer when their teeth first come forth, and they are in great danger when their crest first grows out, Palladius l. 1. de re rustica c. 20. When in the night they double their clanging note, it foreshews rains at hand. The cause is said to be, that by doubling of that troublesome noise, is shewed, that with heat that sharp vocal spirit breaks forth, Mizaldus. Their flesh will not corrupt easily. After a whole year it will not stink, onely it appears drier. Antonius Gigas gave a piece of the boyl’d flesh to Aldrovandus in 1598; it was boyl’d Anno 1592; and it was full of round holes quite through, like a sieve, out of which, if it were a little shaked, dust did fall, as rotten powder doth out of some Trees; it was salt in taste, and somewhat bitter, Aldrovand.[16]

His account does, however, show the lengths to which Aldrovandi would go in the pursuit of knowledge: eating a six-year old piece of peacock flesh would be a step too far these days!

Peacock, Pavo cristatus (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1901.306.1. © NMI

To be fair to Jonstonus, he was not the only one to rely on Aldrovandi’s seminal description: even Willughby and Ray resorted to reproducing Aldrovandi’s account of a bird which Willughby judged was ‘so well known every where, and so sufficiently characterized by the length and glorious eye-like spots of his Tail alone, that it may perchance seem superfluous to bestow many words on describing of it’.[17] Aldrovandi’s description was certainly worth copying:

In the Cock (saith he) the Head, Neck, and beginning of the Breast are of a deep blue. The Head in proportion to the body little, and (as Albertus notes) in a manner Serpentine, adorned with two oblong white spots, the one above the Eyes, the other, (which is the lesser, but much the thicker) under them, which is also succeeded by a black one; else, as I said, blue. It hath a tuft on the top of its head, not entire, as in some other birds, but consisting of a kind of naked, but very tender, green stalks or shafts of feathers, bearing on their tops as it were Lily-flowers of the same colour. Of which most beautiful tuft or crest thus Pliny, Pavonis apicem crinitae arbusculae constituunt: And indeed they seem not to be feathers, but the tender shoots of Plants newly put forth. The Bill is whitish and slit wide, being a little crooked at the tip, as it is in almost all granivorous birds, and in it wide Nosthrils: The Neck long, and for the bigness of the Fowl very slender. The Back of a pale ash-colour, besprinkled with many transverse black spots. The Wings closed (for spred I cannot see them, who describe it painted by the life) above towards the Back are black, lower towards the Belly and withinside red. The Tail is so disposed, that it is as it were divided into two. For when he spreads it round, certain lesser feathers making as it were an entire Tail by themselves, and being of another, to wit, a dusky colour, do not stand up like those long ones, but are seen extended as in other birds: So that without doubt the longer must needs be inserted into another muscle, by help whereof they are so erected and spread. These long feathers, (as Bellonius writes) spring out of the upper part of the Back near the vent, that is, out of the Rump: And those other lesser ones are made by Nature to support the longer. The Rump is of a deep green, which together with the Tail it erects; the feathers whereof are short, and so disposed, that they do as it were imitate the scales of an Aethiopian Dragon, and cover and take away the sight of part of the long feathers of the Tail. The longer feathers are all of a Chesnut colour, beautified with most elegant gold lines tending upward, but ending in tips of a very deep green, and those forked like Swallows Tails. The circular spots, or (as Pliny calls them) the eyes of the feathers, are particoloured of a deep green, shining like a Chrysolite, a Gold and Sapphire colour. For those Eyes consist of four circles of different colours, the first a golden, the second a chesnut, the third a green: The fourth or middle place is taken up by a blue or Sapphire coloured spot, almost of the figure and bigness of a Kidney-bean. The Hips, Legs and Feet are of an ash-colour besprinkled with black spots, and armed with spurs after the manner of Dunghil-Cocks. The Belly near the Stomach is of a bluish green, near the vent it is black, or at least of a dusky colour.[18]

The reference to an Ethiopian dragon might sound strange but Aldrovandi had a keen interest in dragons of all kinds and had devoted a whole book to serpents and dragons – including ones said to be from Ethiopia. In fact he claimed to have been given a mummified one as a present!

Peacocks’ feathers might have reminded him of his ‘Ethiopian dragon’ but though he commented on the beauty of their feathers he was not enamoured of them generally for he complained that:

Though he be a most beautiful bird to behold, yet that pleasure of the Eyes is compensated with many an ungrateful stroke upon the Ears, which are often afflicted with the odious noise of his horrid, or, as he calls it, hellish cry. Whence by the common people in Italy it is said to have the feathers of an Angel, but the voice of a Devil, and the guts of a Thief.[19]

Not only that but they played havoc with his garden for Aldrovandi complained that ‘They are pestilent things in Gardens, doing a world of mischief: They also throw down the Tiles, and pluck off the Thatch of houses!’[20]

Conrad Gessner, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), p. 146: Male capercaillie.

This splendid image of a male capercaillie comes from Gessner’s Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), where he mixes information from medieval sources such as the thirteenth-century Albertus Magnus, with contemporary commentators, such as the Scottish philosopher and historian Hector Boece (1465?–1536).[21] A capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) is a large grouse species, which forms its nest on the ground, preferably in forested mountain areas (hence its colloquial name ‘Cock of the Wood’). It is one of eighteen grouse species and like other grouse species, is particular about its habitat.[22] Male capercaillies are bigger than females and they also differ in other ways. First of all the male capercaillie is a darker colour than the female and, has a ‘red streak’ over its eye which is missing in females. It also has white markings, most notably on its tail but also on the stomach. Its bill is white and curved and, as the image below demonstrates, it has a ‘beard’ of stiff feathers on its throat. The female is a mixture of grey, white and black, with a predominant fawn colour but it has a recognisable red-brown breast.[23]

Capercaillie (male), Tetrao urogallus (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1932.78.1. © NMI

Willlughby and Ray provided a detailed description of the bird, one which was evidently based on eye-witness testimony for they tell us that on their journey ‘At Venice and Padua we saw many to be sold in the Poulterers Shops, brought thither from the neighbouring Alps’:

For bigness and figure it comes near to a Turkey. The Cock we measured from the point of the Bill to the end of the Tail was thirty two inches long: The Hen but twenty six. The ends of the Wings extended were in the Cock forty six inches distant, in the Hen no more than forty one. It had such a Bill as the rest of this kind, an inch and half long, measuring from the tip to the angles of the mouth; its sides sharp and strong. Its Tongue is sharp, and not cloven. In the Palate is a Cavity impressed equal to the Tongue. The Irides of the Eyes are of a hazel colour. Above the Eyes is a naked skin of a scarlet colour, in the place and of the figure of the Eyebrows, as in the rest of this kind. The Legs on the forepart are feathered down to the foot, or rise of the Toes, but bare behind. The Toes are joyned together by a membrane as far as the first joynt, then they have on each side a border of skin all along, standing out a little way, and serrate. The Breast is of a pale red, with transverse black lines, the tips of the feathers being whitish. The bottom of the Throat is of a deeper red: The Belly cinereous. The upper side of the body is particoloured of black, red, and cinereous, the tips of the feathers being powdered with specks, excepting in the Head, where the black colour hath a purple gloss if beheld in some positions. The Chin in the Cock is black, in the Hen red. The Tail is of a deeper red than the other feathers, and crossed with black bars; the tips of the feathers being white. The Tail of the Cock is black, the tips of the feathers being white, and their borders as it were powdered with reddish ash-coloured specks. The middle feathers especially, and those next to them are marked with white spots. The feathers covering the bottom of the Tail have white tips, else are variegated with alternate black and reddish ash-coloured transverse lines. After the same manner the whole Back is also painted with black and white cross lines, but finer, and slenderer. The feathers under the Tail are black, but their tips and exteriour edges white.

The Head [in the Hen] is of the same colour with the back. The tips of the Breast-feathers are black. Each Wing hath twenty six quill-feathers, the greater whereof are of a more dusky and dark colour: The rest have their exteriour Vanes variegated with red and black. The tips of all beside the ten outmost are white. The longer feathers springing from the shoulders are adorned with angular beds of black, wherewith a little red is mingled below. The lesser rows of hard feathers of the Wings are variegated with dusky, red and white, their tips being white. In the Cock the shoulders and lesser rows of hard feathers above are variegated with red and black lines, underneath are white, except those under the first internodium, which are black. The longer feathers under the shoulders are white, which when the Wings are closed make a large white spot. The Wings under the second internodium are black, with transverse lines of white. In the Cock the Neck is of a shining blue. The Thighs, Sides, Neck, Rump, and Belly are in like manner variegated with white and black lines. The Head is blacker: About the vent it is of an ash-colour. It hath very long blind Guts, straked with six white lines. The Stomach musculous, as in the rest of this kind, full of little stones. The Craw was stuft with the Leaves, Tops, and Buds of the Fir-tree. The skin of the stomach sticking to the muscles is soft and hairy like Velvet.[24]

Willughby and Ray linked the bird to Ireland (where they noted it was called ‘Cock of the Wood’).[25] There were reputed sightings in Ireland since the Middles Ages, and County Tipperary seems to have been the locale for them in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries but they were said to have become extinct in Ireland by the later eighteenth century.[26] Willughby and Ray stated they had not seen an example in England.[27] As Sir Robert Sibbald’s account shows, if they had travelled north to Scotland, they might have been more lucky!

Robert Sibbald, Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684), Tab XIV: detail of a female capercaillie.

Gessner’s account of a capercaillie was referenced in Worth‘s copy of Sir Robert Sibbald’s Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684).[28] Sir Robert Sibbald (1641–1722), though perhaps more interested in stilts than capercaillies, did provide this image of a female capercaillie and stated:

Tetrao or Urogallus minor of Aldrovandus. Gallus Scoticus and Gallus palustris Scoticus of Gener, called by us the Black-Cock, common on our moors and marshes. The hen is called Grygallus Major by Gesner and Aldrovandus. It provides most delicate food.[29]

The latter endorsement was not good news for capercaillies. While chickens might have been favourites on the medieval and early modern menu, western capercaillies also featured. This was true not only in Scotland but also in far-off Estonia as the archaeological investigations of Ehrlich et al. have demonstrated.[30]

In 2006 Wormworth and Mallon, in a World Wildlife Fund report on climate change and bird species, noted that the capercaillie was at that point one of the UK’s most threatened birds.[31] Writing five years later Saniga pointed to one important factor in the capercaillie decline: the destruction of their natural habitat. Capercaillies, as previously noted, like to nest in forests (particularly old forests), and thus a change in forest use can severely impact their habitats.[32] Saniga attributes the decline in western capercaillies in the Western Carpathian mountains in Slovakia to a number of factors: predation is obviously a major cause but so too is a change in forest use and, more generally climate change, with its accompanying ‘deteriorating climatic conditions’ causing long-term damage to their habitats.[33] This decline is not localised to Slovakia – as Saniga notes ‘In recent few decades, populations throughout most of western Europe have declined markedly’.[34] Pettersson and Boman agree, ‘Capercaillie numbers have been reduced in mainland Europe and British Isles during the last century mainly due to increased predator populations, habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation as a result of human development of agriculture and land use change’.[35]

Capercallie (female), Tetrao urogallus (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1906.228.1. © NMI

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Ehrlich, Freydis, Ülle Aguraiuja-Lätti and Arvi Haak, ‘Zooarchaeological evidence for the exploitation of birds in medieval and early modern Estonia (ca 1200–1800)’, Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 27, no. 3, (2023),105–122.

Funk, Holger, ‘John Caius’s contributions to Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium and “Historia plantarum”: a survey with commentaries’, Archives of Natural History, 44, no. 2 (2017), 334–351.

Gould, Stephen Jay, ‘Both Neonate and Elder: The First Fossil of 1557’, Paleobiology, 28, no. 1 (2002), 1–8.

Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657). This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

Lind, L. R. (ed.), Aldrovandi on chickens (Norman, Okla., 1963).

Mullens, W. H., ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, British Birds, 6, no. 2 (1912), 34–57.

Nutton, Vivian, ‘John Caius and the Linacre tradition’, Medical history, 23 (1979), 373–391.

Nutton, Vivian, ‘Conrad Gesner and the English naturalists’, Medical history, 29 (1985), 93–97.

Pettersson, Andreas, and Christer Moreira Boman, ‘Limiting factors in capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) conservation’, Bachelor Degree in Forest Science (University of Umeå), 2019.

Saniga, Miroslav, ‘Why the capercaillie population (Tetrao urogallus L.) in mountain forests in the Central Slovakia decline?’, Folia Oecologica, 38, no. 1 (2011), 110-17.

Stevenson, Gilbert Buchanan, ‘An historical account of the social and ecological causes of Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus extinction and reintroduction in Scotland’, D. Phil. (University of Sterling), 2007.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

Wormworth, Janice, and Karl Mallon, Bird species and climate change: The Global Status Report: a synthesis of current scientific understanding of anthropogenic climate change impacts on global bird species now, and projected future effect (Sydney, 2006).

__

[1] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 20. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[2] Lind, L. R. (ed.), Aldrovandi on chickens (Norman, Okla., 1963), p. 393.

[3] Ibid.

[4] On this see Funk, Holger, ‘John Caius’s contributions to Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium and “Historia plantarum”: a survey with commentaries’, Archives of Natural History, 44, no. 2 (2017), 334–351.

[5] Ibid., 335.

[6] On Caius see Nutton, Vivian, ‘John Caius and the Linacre tradition’, Medical history, 23, no. 4 (1979), 373–391.

[7] Funk, ‘John Caius’s contributions to Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium and “Historia plantarum”: a survey with commentaries’, 347.

[8] Lind, Aldrovandi on chickens, p. 395.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., p. 397.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Jonstonus, Joannes, An history of the wonderful things of nature set forth in ten severall classes wherein are contained I. The wonders of the heavens, II. Of the elements, III. Of meteors, IV. Of minerals, V. Of plants, VI. Of birds, VII. Of four-footed beasts, VIII. Of insects, and things wanting blood, IX. Of fishes, X. Of man. Written by Johannes Jonstonus, and now rendred into English by a person of quality (London, 1657), p. 189. This English translation is not in the Worth Library.

[17] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 158.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., p. 159.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), p. 146.

[22] Stevenson, Gilbert Buchanan, ‘An historical account of the social and ecological causes of Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus extinction and reintroduction in Scotland’, D. Phil. (University of Sterling, 2007), p. 29.

[23] Ibid., p. 32.

[24] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 172.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Stevenson, ‘An historical account of the social and ecological causes of Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus extinction and reintroduction in Scotland’, pp 87–8. Stevenson suggests that these birds might not have been capercaillie but other grouse species.

[27] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 172.

[28] Mullens, W. H., ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, British Birds, 6, no. 2 (1912), 39.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ehrlich, Freydis, Ülle Aguraiuja-Lätti and Arvi Haak, ‘Zooarchaeological evidence for the exploitation of birds in medieval and early modern Estonia (ca 1200–1800)’, Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 27, no. 3, (2023),110; 116.

[31] Wormworth, Janice, and Karl Mallon, Bird species and climate change: The Global Status Report: a synthesis of current scientific understanding of anthropogenic climate change impacts on global bird species now, and projected future effect (Sydney, 2006), p. 45.

[32] Saniga, Miroslav, ‘Why the capercaillie population (Tetrao urogallus L.) in mountain forests in the Central Slovakia decline?’, Folia Oecologica, 38, no. 1 (2011), 110-17.

[33] Ibid., 115.

[34] Ibid., 110.

[35] Pettersson, Andreas, and Christer Moreira Boman, ‘Limiting factors in capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) conservation’, Bachelor Degree in Forest Science (University of Umeå), 2019.