Aldrovandi on Chickens and Hens

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), devoted a large section of his three-volume Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] to ‘domestic fowl who bathe in the dust’ – chickens and hens. His definition of them as dust-bathers was not his own. As he mentioned in his chapter on their ‘Nature, habits and character’, ‘According to Aristotle, hens are not high-flying but dust-bathing birds. They enjoy the dust very much’.[1] While he considered wild birds to be ‘superior’ to domesticated chickens and hens, he did not stint on the latter subject, and, indeed, found much to commend in the love demonstrated by hens to their chicks.[2]

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637), ii, p. 309: bantam hen.

His book on the subject, which is Book XIV in his second volume on birds, is a fascinating exploration of all things connected with chickens. Its structure mirrored that of his other books and he thus began by defining his terms and synonyms and then proceeded to investigate the following:

Differentiae of the genus; The form and description of the rooster and the hen in their genus; Anatomical details; Sex; Sight; Taste; Voice; Song; Lustfulness; Coition; Parturition; Incubation; Generation; Egg-laying; Rearing; Feeding; Nature; Habits; Character; Magnanimity; Fighting; Sympathy; Antipathy; Concerning the diseases of chickens; The method of catching chickens; History; Synonyms; Derivatives; Presages; Use in the sacred rites of the pagan; Auguries; Prodigies; Mystical interpretations; Moral interpretations; Secret signs (hieroglyphics); Dreams; Emblems; Riddles, Epitaph; Apophthegms; Proverbs; Fable; Apologues; Use in medicine; Injurious effects of chickens; use of the chicken as food; various other uses of the chicken; insignia; images; coins.[3]

This list of topics reminds us that Aldrovandi, though he took a scientific interest in such matters as the anatomy and physiology of chickens, also took a much broader view and employed an encyclopaedic approach to birds. He attempted to provide his readers with everything that had been (or could be) said about chickens and, as Lind notes, the variety of the sources mentioned in the 574 notes he included was extremely impressive, ranging from the ancient Greek poet Homer to contemporary authors of the later sixteenth century.[4]

Aldrovandi was also keen to provide his readers with images and descriptions of specific birds. One of the first was the above image of a ‘bantam hen’, which he described as follows:

Although I said I would not show another picture of the common hens, I have decided to exhibit one of a bantam, or dwarf, which I said many people mistake for Hadrianic hens, because they are less common. This hen was entirely black except for the larger wing feathers, which were white at the tips. She also had white spots around her neck in the shape of half moons and round, rather yellowish spots around the eyes. Her head had curly ringlets. Her wattles and crest (which was quite small) were a rather deep red; her feet, yellow; her small nails of a very white colour. But why describe her more exactly if often, in fact always, colour varies in these hens as it does in others?[5]

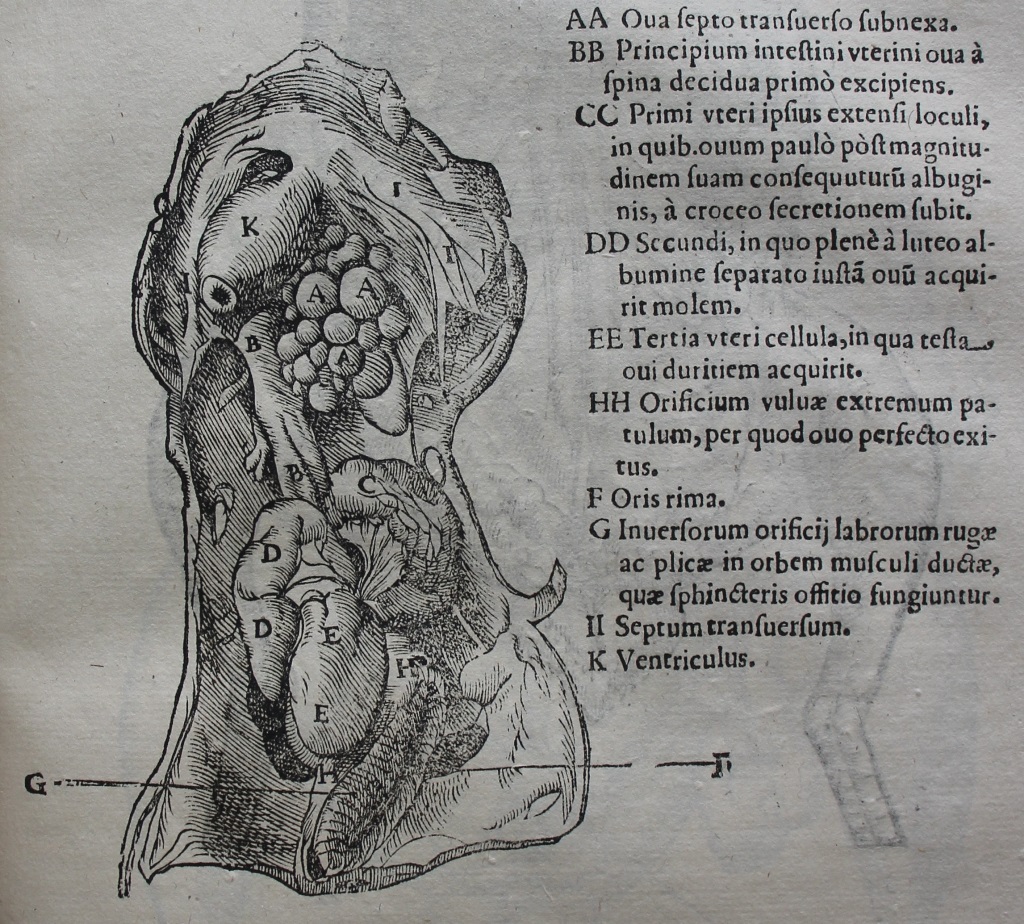

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637), ii, p. 209: anatomy.

Given Aldrovandi’s fascination with bird anatomy, it is no surprise to find that he provided his readers with a number of graphic anatomical illustrations. This image was designed to show his readers how eggs developed and Aldrovandi provided the following key to the woodcut:

-

- AA. Eggs joined to the transverse septum.

- BB. The beginning of the uterine intestine which first receives the eggs when they descend from the spine.

- CC. The first extended compartments of the uterus itself in which the egg, shortly after about to attain its full size, undergoes the separation of the white from the yolk.

- DD. The second compartments in which the egg acquires its proper size when the albumen is fully separated from the yolk.

- EE. The third cell of the uterus in which the egg shell acquires its hardness.

- FF. The open extreme orifice of the vulva through which the egg issues when it is completed.

- GG. The crevice or opening of the mouth.

- HH. Wrinkles and folds of the lower lips of the orifice drawn out into the circle or orbit of the muscle which performs the function of the sphincter.

- II. Transverse septum (diaphragm).

- JJ. Bell (or stomach).[6]

Aldrovandi makes it clear that his anatomical images were based on scientific dissection: ‘I have therefore exhibited some hens for the common benefit of students in a dissection by the most excellent D. M. Antonio Ulmo. He had set forth the entire operation to view most clearly in five pictures’.[7] The above illustration was the first of the set and, was designed to show ‘the size of the eggs conceived under the septum, and the place through which they descend into the uterus; likewise the place in which the yolk is surrounded by the albumen, together with that where the eggshells acquire hardness and other places designed for generation’.[8] The other images were close-ups of the process. Aldrovandi’s collaborator, Marco Antonio Ulmo (fl. 1561), had been responsible for a 1561 Venetian edition of the Observationes anatomicae of Gabriele Falloppio (1523–62), the renowned Professor of Anatomy, Surgery, and Botany at the University of Padua (1551–62).

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637), ii, p. 219: position of a chicken in its shell.

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637), ii, p. 219: position of a chicken in its shell.

This image comes from Aldrovandi’s lengthy discussion of the generation and laying of eggs – always a topic of much interest to early modern commentators, since Aristotle (384-322 BC), had paid particular attention to the relationship of egg shell and membranes. As Aldrovandi noted, ‘Aristotle seems to hint at the existence of only one tunic of this kind in these words: ‘The various parts of the egg are arranged in this order. First and outermost nearest the shell lies the membrane of the egg, not the one native to the shell but the other membrane lying beneath it’’.[9] Aldrovandi sought to clarify what Aristotle had said in the light of his own experiments:

This is as if he had said all parts of the egg are located in this order. The first and last membranes are placed close to the shell. He means, according to my judgment by first and last membrane those membranes recently created in the incubated egg, of course those which I sometimes called the afterbirth (the third membrane) and the fourth, which I said enveloped the foetus. For when Aristotle says the membrane is not native to the shell he shows that it is neither the first nor the second membrane, which is found in the other part of the egg. He therefore seems to exclude this native or first membrane and the second, and to understand the third, which I have often called the afterbirth. When he says “but the other membrane lying beneath it,” he means the same afterbirth lying under the shell, which is certainly very clear from the fact that he says there is a white liquid in it. This liquid, as I showed above, is contained between the third and fourth membranes.[10]

He noted that his own researches had thus disproved the analysis of ‘Suessanus’ and the early to mid-twelfth-century writer Michael of Ephesus. ‘Suessanus’ here refers to Agostino Nifo (c. 1473–1545?), a noted Renaissance commentator on Aristotelianism. This process was impossible to depict but Aldrovandi did provide his readers with the above image, which was intended to represent the ‘position of the now completed chick in the uterus’.[11] His investigations in this particular case had a happy outcome for Aldrovandi tells us that on the twentieth day of his vigil the chick broke the egg shell ‘of its own accord’.[12]

Chicken eggs, NMINH:1910.388.1. © NMI

Perhaps the most obvious problem in depicting birds in the early modern period was the fact that woodcuts and engravings were rarely coloured. Aldrovandi’s detailed notes about the colour of birds’ feathers was thus vital since the woodcuts accompanying the printed text, while beautifully executed, were in black and white. Perhaps for this reason he was clearly more interested in describing more colourful male birds and though he offered his readers images of both a male and female, his descriptions often concentrated on the male. This is readily apparent in his description of ‘Paduan Hens’, which he noted were ‘somewhat larger chickens’, where he only mentions the female at the end of his note on the bird:

The male is very beautiful and adorned with five colours: black, white, green, red, and yellow. The entire body is black. The neck is covered with very fine feathers. The wings and back are partly black, partly green. The tail likewise is of the same colour, but the roots of the feathers are white. Some wing feathers are also white. The head has a beautiful set of curly ringlets; their roots are white. Red spots encircle the eyes. The crest is small; the beak and claws, yellow. There is no white anywhere except that white skin near the foramina of the ears, but it is entirely shaded from black to green. The feet are yellowish; the crest, quite small, also of barely red colour. A naked or plain stalk of oats is pictured beside the male, and a shoot of canary grass beside the female’.[13]

Aldrovandi would have had ample opportunity to study Padua chickens while he studied philosophy, mathematics and medicine at the University of Padua.

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637), ii, p. 310: Paduan hen.

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Ornithologiae hoc est de auibus historiae libri … XII[I] (Bologna, 1637–46).

Lind, L. R. (ed.), Aldrovandi on chickens (Norman, Okla., 1963).

[1] Lind, L. R. (ed.), Aldrovandi on chickens (Norman, Okla., 1963), p. 142.

[2] Ibid., pp 3; 142–3.

[3] Ibid., p. xiii.

[4] Ibid., pp xxxiii.

[5] Ibid., p. 353.

[6] Ibid., p. 77.

[7] Ibid., p. 77.

[8] Ibid., pp 77; 82.

[9] Ibid., p. 96.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., p. 355.