Waders

Conrad Gessner, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), Book III, p. 692 (to the left) and Pierre Belon, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 210 (to the right): Lapwing.

Neither Conrad Gessner (1516–65), nor Pierre Belon (1517–64), could resist the appeal of the lapwing. Gessner tells us that the bird owed its Latin name ‘Vanellus’ to two medieval writers: the author of De Natura Rerum (Thomas of Cantimpré (1201–72)), and Albertus Magnus (d. 1280), but that in France it was called ‘Vanneau’.[1] While a lapwing might not appear to us to have much in common with a peacock, Gessner noted that it was thought by some to be one, due to the way it raised its crest when startled and added that around Padua it was called a ‘little peacock’ because of its colour and crest![2] He drew particular attention to its crest and noted that this beautiful bird (which he had once examined himself), was about the size of a pigeon.[3]

In his L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), which appeared in the same year as the first edition of Gessner’s book on birds, the French natural historian Belon elaborated on lapwings, a bird which he stated ‘was known in all places’.[4] Clearly he himself was very familiar with the bird for he provides us with a much more detailed description, telling us that its famous crest was comprised of five or six delicate black feathers and that the feathers in the underside of the wing were black also.[5] It is quite clear also that for Belon this was a hands-on experience – he talks about turning the bird and holding it by the beak, and examining the roots of the feathers of its crest which, unlike a lark, emerged from the very top if its head.[6] Belon was attracted to the colour scheme of the lapwing – he drew attention to the fact that the feathers at the root of its tail were tawny, but that the feathers underneath the tail were white with black tips – with one exception on either side which were totally white. He linked the lapwing with other birds with crests, such as the heron, egret, hoopoe, lark and peacock. Like Gessner, he too drew attention to the noise of its flight.[7]

Lapwing; Bull Island, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Belon was not the only one to get his hands on a lapwing. Francis Willughby (1635–72), and John Ray (1627–1705), also examined the Vanellus vanellus in detail and provided perhaps the most extensive early modern commentary of the bird they called ‘The Lapwing or Bastard Plover: Capella sive Vannellus’:

This Bird is in all Countries very well known; and every where to be met with. In the North of England they call it the Tewit, from its cry. It is of the bigness of a common Pigeon, of eight ounces weight; thirteen inches and an half length, measuring from Bill to Claws, and not much less from Bill to Tail: Its breadth, taken between the tips of the Wings spread out, is twenty one inches. The top of the Head above the Crest is of a shining black. The Crest springs from the hind part of the Head, and consists of about twenty feathers, of which the three or four foremost are longer than the rest, in some birds of near four inches length. The Cheeks are white; only a black line drawn under the Eyes through the Ears. The whole Throat or under side of the Neck, from the Bill to the Breast is black, which black part somewhat resembles a Crescent, ending in horns on each side the Neck. The Breast and Belly are white: As are also the covert feathers of the underside of the Wings. The feathers under the Tail are of a lovely bright bay: Those above the Tail are of a deeper bay: The feathers next them are dusky, with a certain splendour. The middle of the Back and the scapular feathers are of a delicate shining green, adorned with a purple spot on each side next the Wings. The utmost edges of the tips of the middlemost of the long scapular feathers are whitish. The Neck also is of an ash-colour, with a mixture of red and some black lines near the Crest.

Of the master-feathers of the Wing the three or four outmost are black, with white tips: The following to the eleventh are black. From the eleventh they are white at bottom, the hindmost more and more in order than the foremost. Yet this white doth not appear in the upper side of the Wing, but is hid by the covert-feathers. Those next the body from the twenty first are green. The lesser covert-feathers are beautified with purple, blue, and green colours, variously commixt. The outmost feather of the Tail on each side is white, saving a black spot in the exteriour Web. The tips of all the rest are white, and beneath the tips the upper half black, and the lower white. The Bill is black, hard, roundish, of an inch length. The upper Mandible a little more produced: The Tongue not cloven; but its sides reflected upwards make a channel in the middle. The Nosthrils oblong, and furnished with a flexile bone. The Ears seem to be situate lower in this than other Birds: The Eyes are hazel-coloured. The Feet are long, reddish [in some Birds brown.] The back-toe small. The outmost of the fore-toes joyned to the middle one at the bottom.[8]

Clearly both Willughby and Belon had dissected this common wader.

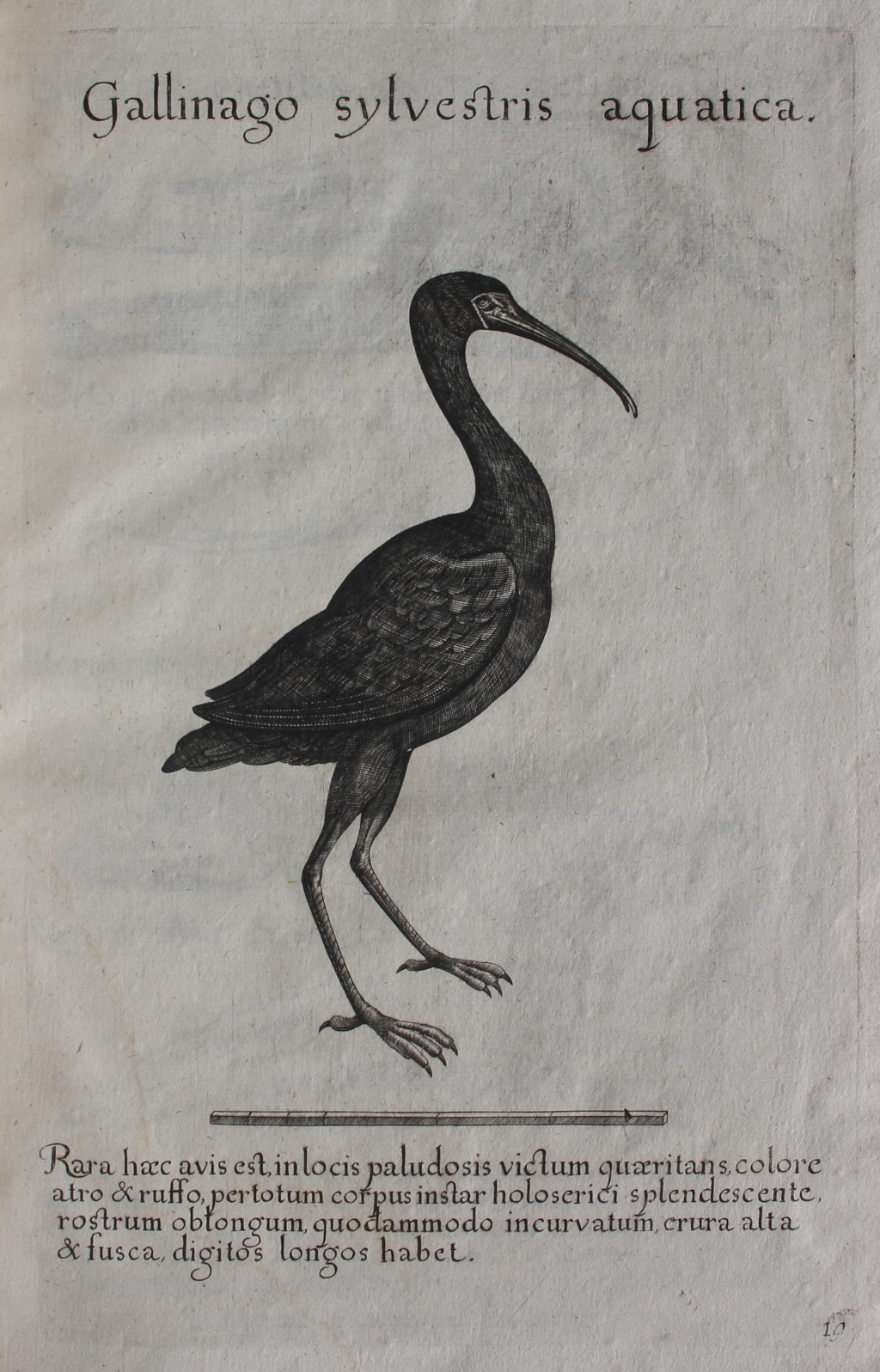

Michael Rupertus Besler, Gazophylacium rerum naturalium: e regno vegetabili, animali & minerali depromptarum, nunquam hactenus in lucem editarum, cum figuris aeneis ad vivum incisis, opera Michaelis Ruperti Besleri (Leipzig and Frankfurt, 1716), plate 19: Glossy Ibis.

A far rarer bird was included in Gazophylacium rerum naturalium (Leipzig and Frankfurt, 1716), of the German physician Michael Rupertus Besler (1607–61), who noted the rarity of the ibis, along with its dark red plumage, and the fact that it was to be found in marshy areas.[9] Besler, the nephew of Basil Besler (1561–1629), was, like his uncle, a collector of curiosities, and in 1642 he published a beautifully illustrated guide to their joint collection.[10] Worth was lucky enough to possess a 1716 Leipzig and Frankfurt edition. Schuh notes that Besler’s collection not only included this attractive Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus but also the ever popular Bird of Paradise and, in addition, the beak of a hornbill.[11]

The Glossy Ibis was not the only ibis Worth would have encountered in the leaves of his ornithological books. Belon talks about a ‘black ibis’ and it is clear that for this bird Willughby and Ray were heavily dependent on Belon’s text for they omit their usual precise measurements. Here Belon admits that he initially mixed up ibises and stilts:

Formerly (saith he) we took the black Ibis to be the Haematopus: But observing its manners and conditions, we found it not to be the Haematopus, but the black Ibis, which Herodotus first mentioned, and after him Aristotle. It is of the bulk of the Curlew, or a little less, all over black: Hath the Head of a Cormorant. The Bill where it is joyned to the Head is above an inch thick, but pointed toward the end, and a little crooked and arched, and wholly red, as are also the Legs, which are long, like the Legs of that Bird which Pliny calls Bos taurus, Aristotle names Ardea stellaris. It hath a long Neck like a Heron, so that when we first saw the black Ibis, it seemed to us in the manner and make [habitu] of its body like the Bittour. This kind of Bird is said to be so proper to Egypt, that it cannot live out of that Country, and that if it be carried out it dies suddenly.[12]

Given Belon’s description it seems likely that what he saw was a (Northern) Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita, which as Collins Bird Guide notes has a distinctive red bill. This bird could be found in the Middle East – an area through which Belon had travelled in the 1540s.[13] Willughby and Ray, though they travelled extensively, had not had the opportunity to visit the region.

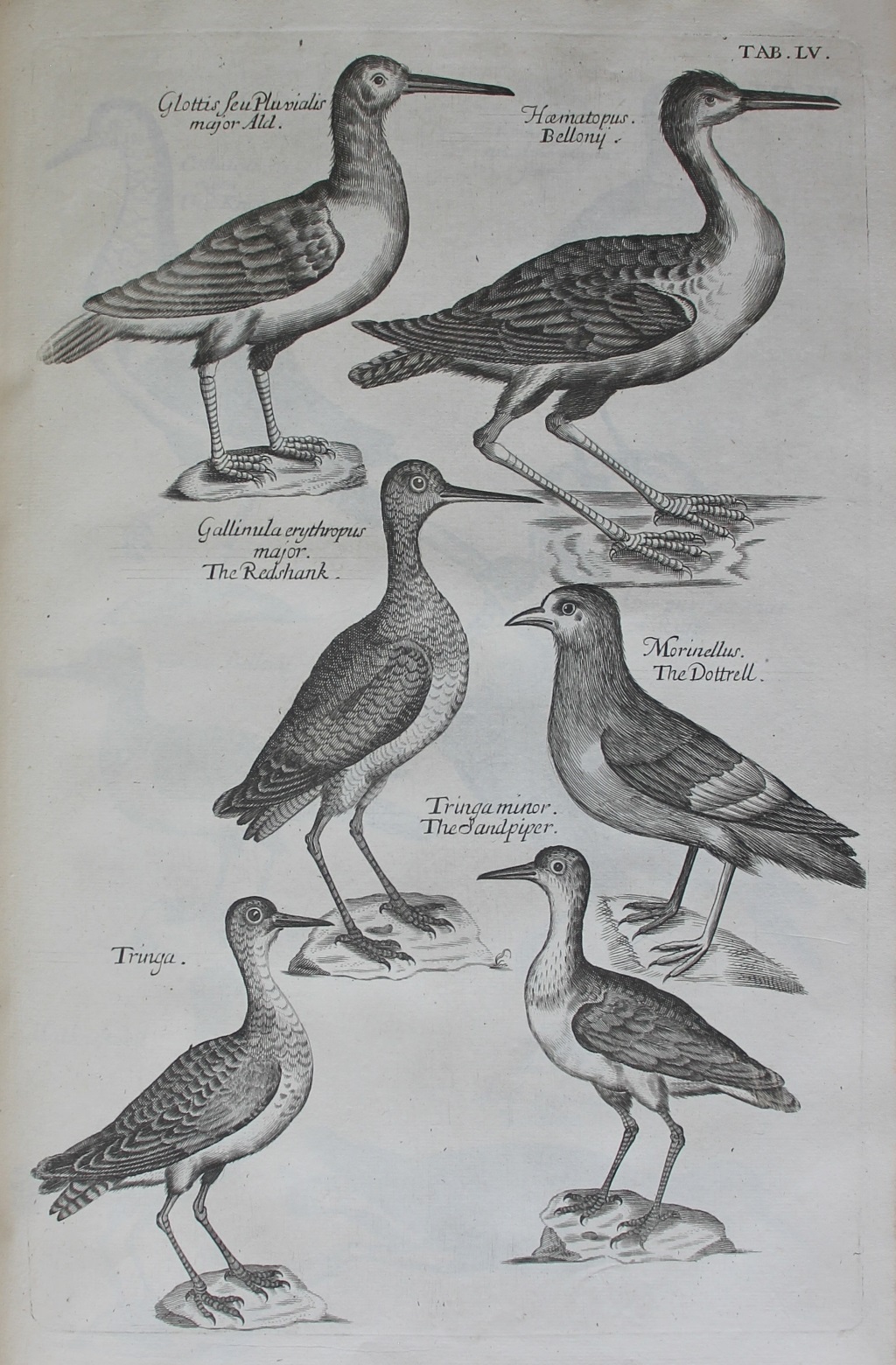

Francis Willughby, Ornithologiæ libri tres (London, 1676), plate LV: A collection of waders.

Willughby and Ray drew together a number of well-known waders in this image, including, among others, a redshank, a sandpiper and a dotterel. These birds, unlike the Bald Ibis, were very familiar to them and they had ample time to examine them in detail. Willughby and Ray, though they did not think much of dotterels (they repeated John Caius’s comment to Gessner that the dotterel was ‘a very foolish bird’), nonetheless provided their readers with a detailed analysis of a Eurasian Dotterel Charadrius morinellus:

The Dottrel: Morinellus Anglorum. The Males in this kind are lesser than the Females, at least they were so in those we hapned to see: For it might fall out to be so among them by some accident. The Female was almost ten inches long, the Male but nine and an half; the Female nineteen inches and an half broad, the Male but eighteen three quarters: The Female weighed more than four ounces; the Male scarce three and an half. The Bill, measuring from the tip to the angles of the mouth, was an inch long: The Head elegantly variegated with white and black spots, the middle part of each single feather being black. Above the Eyes was a long whitish line: The Chin whitish. The Throat is of a pale cinereous or whitish colour, with oblong brown spots. The Breast and underside of the Wings of a dirty yellowish colour, the Belly white. Each Wing hath about twenty five prime feathers, of which the first or outmost is the longest, the tenth the shortest; from the tenth to the twentieth they are almost equal: The rest to the twenty fourth are again longer the foregoing than the following. The first or Pinion-quil hath a broad, strong, white shaft: The three outmost are blacker than the rest, which are of a dusky [or brown] colour, having the edges of their tips whitish. The lesser rows of the Wing-feathers are brown, with yellowish white tips, but those next the quils blackest. The middle of the Back between the Wings is almost of the same colour with them. The Rump and Neck are more cinereous. The Tail is composed of twelve feathers, two inches and an half long, but the middlemost something the longer: The bottoms of all are cinereous, the tips white, the remaining part black: In the outmost feather the white part is broader, in the middle ones narrower: The edges also of the outmost feathers are whitish.

The Legs are bare for a little space above the Knees, of a sordid or greenish yellow; the Toes and Claws darker coloured than the Legs. The inner Toe joyned to the middle only at bottom, the outer by a thick membrane as far as its first joynt. It wants the backtoe, wherein it agrees with the green Plover, from which yet it is sufficiently distinguished by its colour, magnitude, and other accidents. Its Bill is streight, black, and in figure like that of the Plover. It hath a fleshy stomach, in which dissected we found fragments of Beetles, &c. Its guts were fourteen inches and an half long. The Cock and Hen can scarce be known asunder, they are so like in shape, and colour.[14]

Ray, who added a treatise on the art of fowling to the 1678 English edition of the Ornithologia, added information about catching dotterels which he owed to one of his many correspondents:

Of the catching of Dotterels, my very good Friend Mr. Peter Dent, an Apothecary in Cambridge, a Person well skill’d in the History of Plants and Animals, whom I consulted concerning it, wrote thus to me. A Gentleman of Norfolk, where this kind of sport is very common, told me, that to catch Dotterels six or seven persons usually go in company. When they have found the Birds, they set their Net in an advantageous place; and each of them holding a stone in either hand get behind the Birds, and striking their stones often one against another rouse them, which are naturally very sluggish; and so by degrees coup them, and drive them into the Net. The Birds being awakened do often stretch themselves, putting out a Wing or a Leg, and in imitation of them the men that drive them thrust out an Arm or a Leg for fashion sake, to comply with an old custom. But he thought that this imitation did not conduce to the taking of them, for that they seemed not to mind or regard it.[15]

Ray had known the apothecary and naturalist Peter Dent (1628/9–89), since at least 1667, when he mentioned him in passing in a letter to Martin Lister (bap. 1639, d. 1712), and Dent certainly provided Ray with information about a host of different subjects in the intervening years.[16] In 1674 he had sent some wildfowl to Ray and he was particularly helpful with Ray’s researches into fish.[17]

Top left: Redshank, Tringa totanus (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:2003.52.1130. © NMI; top right: Dotterel, Eudromias morinellus (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:1887.40.2. © NMI; bottom right: Sandpiper, Actitis hypoleucos (Linnaeus, 1758), NMINH:2003.52.946. © NMI; bottom left: Greenshank, Tringa nebularia (Gunnerus, 1767), NMINH:2003.52.958. © NMI

Willughby and Ray considered the ‘Redshank or Pool-Snipe’ to be a middle-sized bird, (somewhere between a lapwing and a snipe), and noted that it was commonly found on sandy shores in England and breeding in marshlands (where, if disturbed it set up a great racket, not unlike a lapwing).[18] Yet again it is clear that their analysis of the bird was based on first-hand experience:

The Head and Back are of a dusky ash-colour, spotted with black [In some I observed the Back to be of a dusky or brown colour, in lining to green.] The middle of the Neck is more cinereous. The Throat particoloured of black and white, the black being drawn down longways the feathers. The white colour seems to have something of red mingled with it. The Breast is whiter with fewer spots, and those transverse. The Tail, and feathers next to it are variegated with transverse waved lines of white and black alternately. The number of Tail-feathers is twelve; the length of the Tail two inches three quarters. The quil-feathers in each Wing are twenty six, of which the first is brown, only its shaft white: The five next of a black brown; on the inner side white, and as it were sprinkled or powdered with white. The tip of the seventh is white, with one or two transverse black lines. In the following feathers the white spreads it self further, till in the nineteenth it takes up the whole feather: The foremost covert-feathers are black; the middle varied with white lines. The other rows of covert-feathers are of the same colour with the Back, that is of a dark ash-colour.

The Bill is two inches long, slender, and like a Woodcocks, of a dark red at base, black toward the point. The Tongue is sharp, slender, and undivided; the upper Mandible longer, and something crooked at the very tip: The Eyes hazel-coloured: The Nosthrils oblong. The Legs of a fair, but pale red: The Claws small and black. The back-toe is very small, having a very little Claw. Of the fore-toes the inmost is the least: All are connected by a membrane below; but the outmost with a larger, extending to the second joynt.[19]

With such as detailed description it is not surprising that Sir Robert Sibbald (1641–1722), publishing his Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684), just six years after the English edition of Willughby and Ray’s magnum opus, would merely list the ‘Redshank or Pool-Snipe’ among his list of waders, preferring instead to concentrate on the black-winged stilt.

Redshank; Bull Island, Dublin (c) Derek O’Reilly.

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Alexander, John, ‘Sibbald, Sir Robert (1641–1722), physician and geographer’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Anon., ‘An Account of a Book’, Philosophical Transactions (1683–1775), 14 (1684), 795–98.

Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555).

Besler, Michael Rupertus, Gazophylacium rerum naturalium: e regno vegetabili, animali & minerali depromptarum, nunquam hactenus in lucem editarum, cum figuris aeneis ad vivum incisis, opera Michaelis Ruperti Besleri (Leipzig and Frankfurt, 1716).

Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617).

Jaussaud, Philippe, ‘Les curiosités de trois apothicaires’, Revue d’Histoire de la Pharmacie, 340 (2003), 603–10.

Mullens, W. H., ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, British Birds, 6, no. 2 (1912), 34–57.

Raven, C. E., John Ray, Naturalist: His Life and Works (Cambridge, 1986).

Raye, Lee, ‘Robert Sibbald’s Scotia Illustrata (1684): A Faunal Baseline for Britain’, Notes and Records, 72 (2018), 383–405.

Schuh, Curtis P., ‘Besler, Michael Rupertus (1607–1661)’, in ‘Annotated Bio-Bibliography of Mineralogy and Crystallography 1469-1919’, The Mineralogical Record.

Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022).

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] Gessner, Conrad, Historiae animalium … (Frankfurt, 1617), Book III, p. 692.

[2] Ibid., p. 693.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Belon, Pierre, L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux, avec leurs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du naturel: escrite en sept livres (Paris, 1555), p. 209.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., pp 209–10.

[7] Ibid., p. 209.

[8] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 307. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[9] Besler, Michael Rupertus, Gazophylacium rerum naturalium: e regno vegetabili, animali & minerali depromptarum, nunquam hactenus in lucem editarum, cum figuris aeneis ad vivum incisis, opera Michaelis Ruperti Besleri (Leipzig and Frankfurt, 1716), plate 19.

[10] Jaussaud, Philippe, ‘Les curiosités de trois apothicaires’, Revue d’Histoire de la Pharmacie, 340 (2003), 604.

[11] Schuh, Curtis P., ‘Besler, Michael Rupertus (1607–1661)’, in ‘Annotated Bio-Bibliography of Mineralogy and Crystallography 1469-1919’, The Mineralogical Record.

[12] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 288.

[13] Svensson, Lars, et al., Collins Bird Guide, 3rd ed. (London, 2022), p. 86.

[14] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 309.

[15] Ibid., p. 310.

[16] Raven, C. E., John Ray, Naturalist: His Life and Works (Cambridge, 1986), p. 54.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Willughby and Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick, p. 299.

[19] Ibid.