Sibbald on Stilts

The Scottish physician and geographer, Sir Robert Sibbald (1641–1722), had a number of things in common with the early eighteenth-century Dublin physician Edward Worth (1676–1733): he too studied medicine at the University of Leiden (though in his case in the early 1660s), and he was, likewise, a fascinated devotee of the Royal Society. On his return to Scotland Sibbald was active in setting up a botanical garden in Edinburgh (1667), and he was instrumental in the development of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (1681). In 1684 he produced Pharmacopoia Edinburgensis and the following year he was appointed the first professor of medicine at the University of Edinburgh.[1] Like many other physicians (including Worth), Sibbald had a keen interest in natural history and in 1684 he published his most important work, Scotia illustrata (Edinburgh, 1684), which was a wide ranging exploration of Scotland’s natural history on the Baconian model.[2]

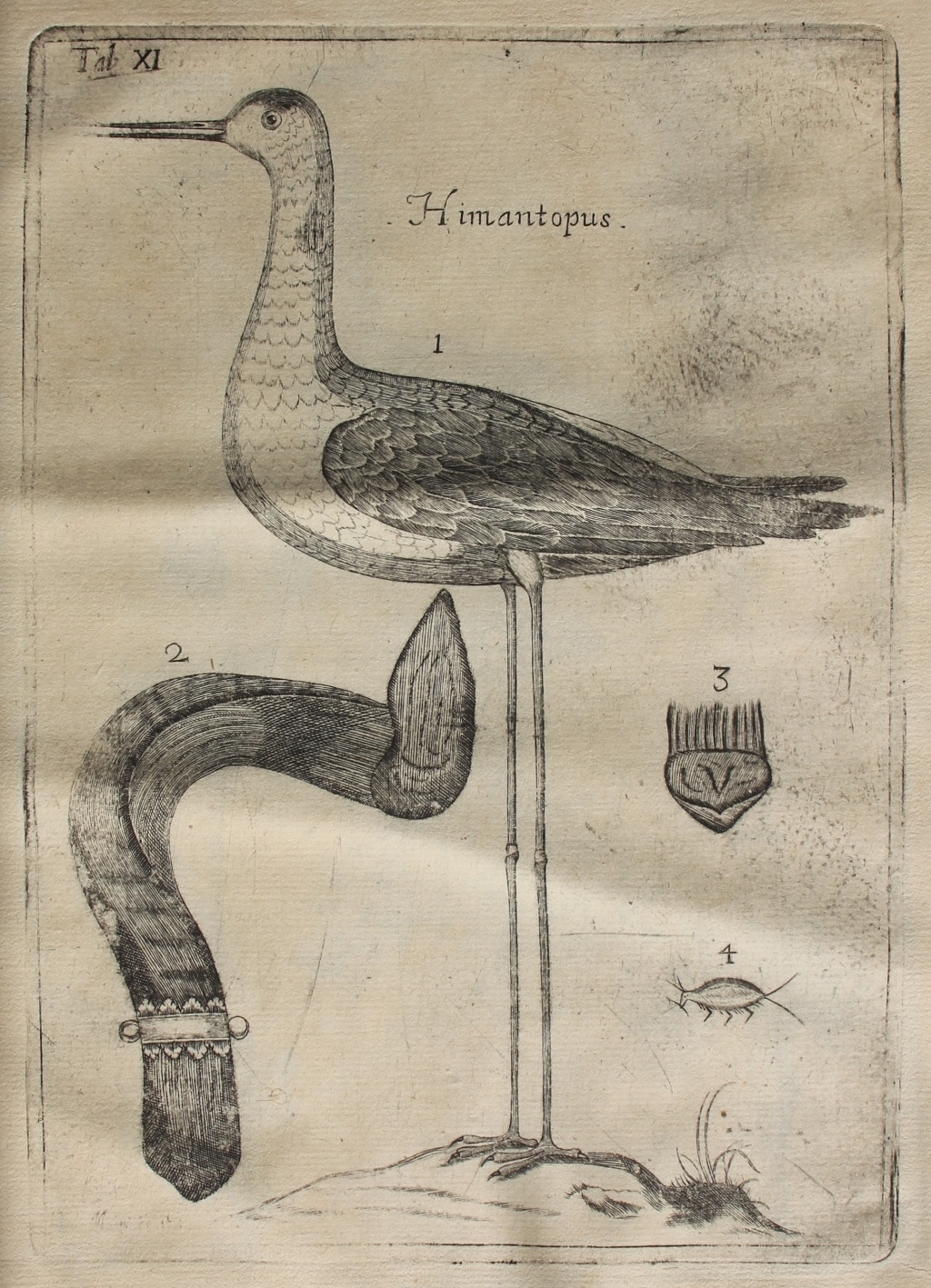

Robert Sibbald, Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684), Tab. XI: Black winged stilt.

Sibbald’s focus in Scotia illustrata was on producing a comprehensive description of all aspects of Scotland’s natural history. As part of this he commented on birds in book III of the second part of his work, and here he divided them into ‘Carnivorous land birds’ (such as eagles, hawks, falcons and owls), but also listed in this chapter were other birds, including corvids such as ravens; woodpeckers; hoopoes and kingfishers. His next chapter focused on ‘grain-eating birds’, where he included peacocks, turkeys, partridges as well as capercaillies; ‘birds which dust and wash themselves’ (pigeons and thrushes). The following chapter ‘Of little birds’ included a listing of larks, swallows and swifts, finches and buntings – among others but in many cases he merely listed the names of birds. It was only in his chapter on ‘Of water birds, with divided feet’ that he provided his readers with an in-depth analysis of one particular bird. This was the black-winged stilt and Sibbald explained that his decision to include more information about the stilt was because it had hitherto been ignored: ‘Himantopus of Pliny, which should be treated of at some length in this history, because it has not been identified by any of those who have treated of Natural History in their writings’.[3] He assured his readers that he had ‘taken care that my figures should represent the bird as it actually is, and I have given as accurate a description of the bird as I am able, from the bird itself’.[4]

Sibbald produced the above image of a stilt, which he said had been sent to him by one of his informants, ‘William Dalmahoy, and officer of the Royal Guard’ after he had shot it near Dumfries.[5] Noting ancient authorities such as Pliny and more modern authorities such as Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), Sibbald concluded that none of them had actually seen a black-winged stilt and he therefore provided his reader with the first description of the bird:

But this Himantopus is white over the whole belly, breast and lower neck, and also on the head between the eyes; but above the eyes it is black, and on the back and wings it is of a black or dusky colour. The bill also is black, it is a span or more in length, slender and fit only for consuming wood-lice or other insects. The tail shades from white to ash colour, it is white underneath. On the back of the neck are black spots tending downwards; the wings, legs, and thighs are of marvellous length, but very slender and fragile, and they are all the weaker for standing on, because the hind toe is lacking, and the front toes are short for the length of the tibia, so that the bird would properly be called Himantopus or Loripes. The toes are of almost equal length, of a blood-red colour, the middle one is slightly longer. The claws are small, black and somewhat re-curved.[6]

It is clear that Sibbald had made a thorough examination of the bird and he was particularly keen to offer his readers his findings concerning the size of the black-winged stilt:

In size it slightly exceed the Lapwing. The length of the whole bird from the top of the head to the end of the middle toe is twenty inches. The beak straight, and two and a half inches in length, the upper part of the beak is longer than the lower, by the ninth of an inch. The neck is three inches long; from the neck to the tip of the tail is seven inches and one-eighth. The length of the wings from end to end is eight inches and seven parts of an inch. The length of the legs, tibia, feet and toes, from the trunk of the bird, where they join on, to the claw of the middle toe is about twelve inches. The upper part of the leg, covered with feathers and muscle, measures one and a half inches; from where the feathers cease to the joint, connecting the tibia with the leg, three and a half inches …[7]

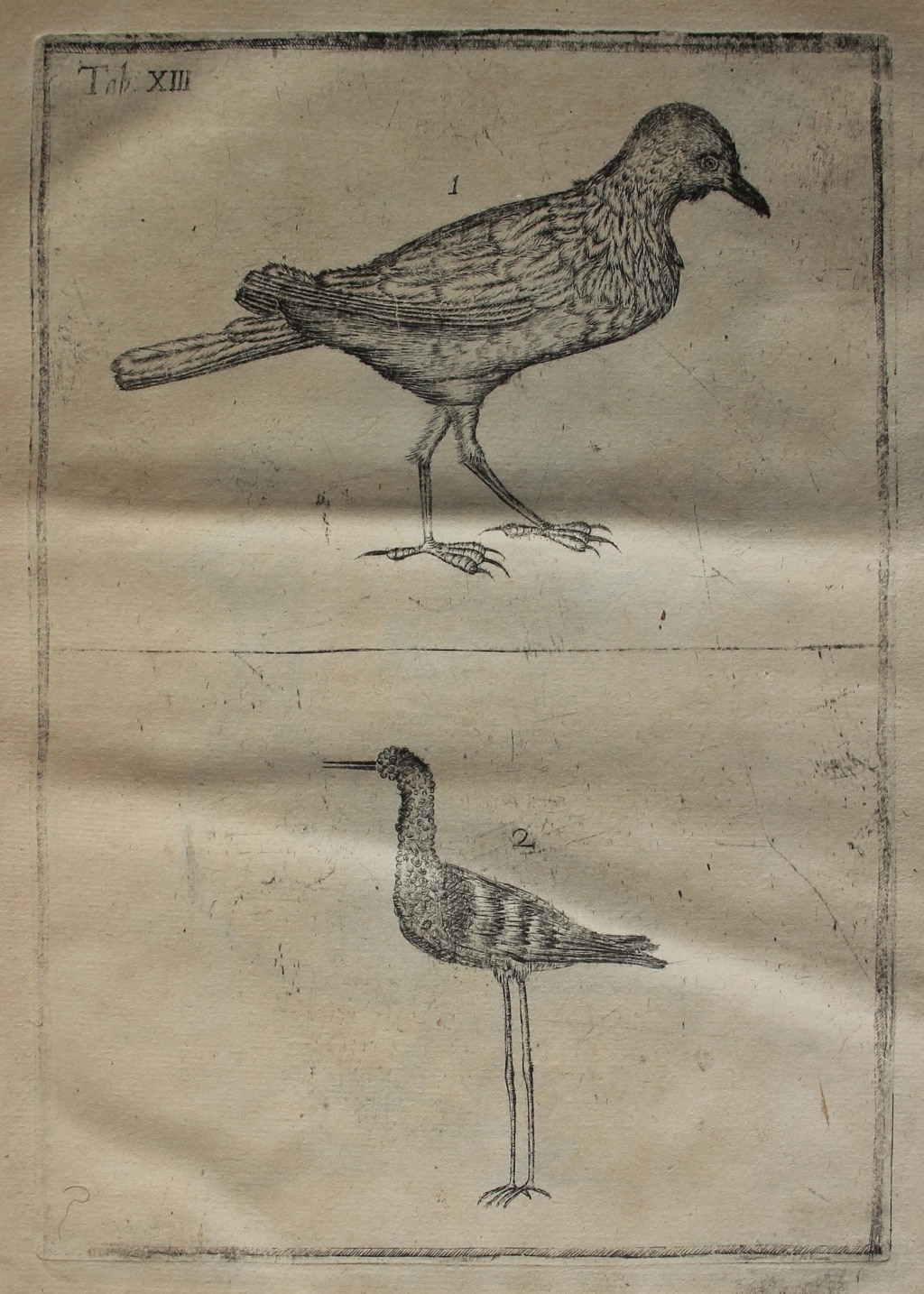

Robert Sibbald, Scotia illustrata sive Prodromus historiae naturalis in quo regionis natura, incolarum ingenia & mores, morbi iisque medendi methodus, & medicina indigena accurrate explicantur … Cum figuris aeneis (Edinburgh, 1684), Tab. XIII: Redwing and black-winged stilt.

As this second image of a stilt in Scotia Illustrata demonstrates, Sibbald’s images left something to be desired. Perhaps for this reason he provided extra notes concerning the coloration of the stilt:

The colour on the head and lower neck is white, on the back and wings, black, mixed somewhat with a greenish tint. The upper part of the tail, and upper neck, shaded from white to ash colour, the under parts are all white, and the upper part of the head is also white. The legs are blood-red colour, as also the three toes, of which the middle is the longest, the inner one the shortest.[8]

With this level of detail few could miss the black-winged stilt in future! Sibbald explained to his readers that his motivation in providing this amount of detail about this particular bird was to aid his readers to correctly identify a bird which noted ornithologists such as Pierre Belon (1517–64), and Conrad Gessner (1516–65), had mis-identified.[9]

The only commentator who Sibbald praised was Francis Willughby (1635–72), ‘the learned Willughby’ who was, in Sibbald’s eyes, ‘that most accurate writer’.[10] Willughby’s and Ray’s description of the bird was in fact based on that of Gessner for they noted that ‘it hath not been our hap as yet to see this bird’.[11] They describe it as follows:

The whole Belly, Breast, and under-side of the Neck is white, as is also the Head beneath the Eyes: For above the Eyes it is black, and so is it too on the Back and Wings. The Bill is likewise black, a Palm and more long, slender, and fit to strike Wood-lice, and other Insects. The Tail from white inclines to ash-colour, but underneath is white. On the upper side of the Neck are black spots tending downward. The Wings are very long. The Legs and Thighs are of a wonderful length, very small and weak, and so much the more unfit to stand upon, because it wants a hind-toe, and the fore-toes for the length of the Legs are short; so that well and of right may it be called Himantopus, or Loripes, its Legs being soft and flexible like a thong or string. The Toes are of almost equal length, and of a sanguine colour, yet is the middle toe a little the longest. The Claws are black, small, and a little crooked.[12]

As you can see, Sibbald’s description of the bird was remarkably similar! Sibbald was, as the above description demonstrates, ‘meticulous in his descriptions’, but unfortunately he provided few of them and his description of the black-winged stilt was his tour-de force.[13]

Black-winged stilt (Himantopus himantopus), iSimangaliso Wetland Park, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Image taken by Charles J. Sharp and made available under CC BY-SA 4.0

File source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Black-winged_stilt_(Himantopus_himantopus).jpg

As Raye argues, the real significance of Sibbald’s project lay in the method of its creation and the vital information it gives us about the natural history of Scotland in the 1680s. For as Sibbald’s account of the black-winged stilt tells us, this was a collaborative project and his results were generated from a multitude of sources and informers across Scotland. The genesis of the project may be seen in the Baconian natural history project, which had been developed further by Robert Boyle (1627–91) in 1666 when he published General heads for the natural history of a country, great or small in the first volume of the Transactions of the Royal Society of London (London, 1666). Sibbald was eager to take up the challenge and duly sent out questionnaires across Scotland asking for information about a host of topics: Scotland’s geography, climate, flora, fauna, geology and, given his medical background, infectious diseases prevalent in the country. Raye notes that Sibbald received ‘at least 77 responses’ in return, which were communicated to him from a wide social strata, from Anne, Countess of Erroll (1656–1708), down to the likes of William Dalmahoy.[14] The resulting publication, Scotia Illustrata, provides readers with information about around 400 different kinds of animals. Identification of these sometimes proves challenging but Raye argues that 274 of these can be identified.[15]

The true significance of Scotia Illustrata for us today is in the information it gives about decline in bird species: the crane (Grus grus), which had been prevalent in Scotland in the medieval period, by the 1680s was becoming increasingly rare – according to Sibbald they were only to be found in the Orkney Islands.[16] As Raye notes, Sibbald’s reference is actually one of the last references to cranes, which were rarely seen in Scotland since the seventeenth century.[17] But Sibbald did not just provide information about how distribution of species had changed from the Middle Ages: by providing a listing of birds found locally in Scotland in the 1680s he allows contemporary conservationists to see what birds we have lost since 1684. It is clear from his decision to include ‘The bird called Gare, like a sea crow, with a very large egg’ [i.e. the Great Auk], in his chapter on ‘Of various kinds of birds found with us which are of uncertain class, and of which an exact description is desired’, that he had not had the opportunity to see a Greak Auk (Pinguinus impennis), and this bird is now extinct.[18] As Raye suggests, Sibbald’s remarks on land fowl such as capercaillies (Tetrao urogallus), and corncrakes (Crex crex), which are currently in decline, are valuable, while the redwing (depicted above his second image of a black-stilt) is also rare.[19] Sibbald’s reference to a bustard (Otis tarda), which he principally owed to the Scottish historian Hector Boece (1465?–1536), and his comment that only a single bustard had been seen in East Lothian since Boece’s day, is, as Raye notes, the ‘final record of the species before it became extinct in Britain’ [20]

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Alexander, John, ‘Sibbald, Sir Robert (1641–1722), physician and geographer’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Anon., ‘An Account of a Book’, Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775), 14 (1684), 795–98.

Mullens, W. H., ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, British Birds, 6, no. 2 (1912), 34–57.

Raye, Lee, ‘Robert Sibbald’s Scotia Illustrata (1684): A Faunal Baseline for Britain’, Notes and Records, 72 (2018), 383–405.

Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678). Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

__

[1] On Sibbald’s life see Alexander, John, ‘Sibbald, Sir Robert (1641–1722), physician and geographer’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[2] On the important of Scotia illustrate see Raye, Lee, ‘Robert Sibbald’s Scotia Illustrata (1684): A Faunal Baseline for Britain’, Notes and Records, 72 (2018), 383–405.

[3] Mullens, W. H., ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, British Birds, 6, no. 2 (1912), 44.

[4] Ibid., 46.

[5] Ibid., 44.

[6] Ibid., 45. All translations are by Mullens.

[7] Ibid., 46.

[8] Ibid., 46–7.

[9] Ibid., 47.

[10] Ibid., 45.

[11] Willughby, Francis, and John Ray, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq, fellow of the Royal Society in three books : wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable to their natures, are accurately described : the descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVII copper plates : translated into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work : to which are added, Three considerable discourses, I. of the art of fowling, with a description of several nets in two large copper plates, II. of the ordering of singing birds, III. of falconry by John Ray (London, 1678), p. 297. Please note that this English translation is not in the Edward Worth Library.

[12] Ibid., p. 297.

[13] Mullens, ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, 55.

[14] Raye, ‘Robert Sibbald’s Scotia Illustrata (1684): A Faunal Baseline for Britain’, 386; 384.

[15] Ibid., 387.

[16] Mullens, ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, 44.

[17] Raye, ‘Robert Sibbald’s Scotia Illustrata (1684): A Faunal Baseline for Britain’, 392.

[18] Mullens, ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, 53.

[19] Raye, ‘Robert Sibbald’s Scotia Illustrata (1684): A Faunal Baseline for Britain’, 392–3.

[20] Mullens, ‘Robert Sibbald and his Prodromus’, 41; Raye, ‘Robert Sibbald’s Scotia Illustrata (1684): A Faunal Baseline for Britain’, 392.